Natural transformation

In category theory, a branch of mathematics, a natural transformation provides a way of transforming one functor into another while respecting the internal structure (i.e., the composition of morphisms) of the categories involved.

Informally, the notion of a natural transformation states that a particular map between functors can be done consistently over an entire category.

Functors and natural transformations abound in algebraic topology, with the Hurewicz homomorphisms serving as examples.

with the elements of the former is itself a homomorphism of abelian groups; in this way we obtain a functor

This is formally the tensor-hom adjunction, and is an archetypal example of a pair of adjoint functors.

Additionally, every pair of adjoint functors comes equipped with two natural transformations (generally not isomorphisms) called the unit and counit.

The notion of a natural transformation is categorical, and states (informally) that a particular map between functors can be done consistently over an entire category.

an isomorphism) between individual objects (not entire categories) is referred to as a "natural isomorphism", meaning implicitly that it is actually defined on the entire category, and defines a natural transformation of functors; formalizing this intuition was a motivating factor in the development of category theory.

This is similar (but more categorical) to concepts in group theory or module theory, where a given decomposition of an object into a direct sum is "not natural", or rather "not unique", as automorphisms exist that do not preserve the direct sum decomposition – see Structure theorem for finitely generated modules over a principal ideal domain § Uniqueness for example.

However, the torus (which is abstractly a product of two circles) has fundamental group isomorphic to

(geometrically a Dehn twist about one of the generating curves) acts as this matrix on

of invertible integer matrices), which does not preserve the decomposition as a product because it is not diagonal.

– equivalently, given a decomposition of the space – then the splitting of the group follows from the general statement earlier.

In categorical terms, the relevant category (preserving the structure of a product space) is "maps of product spaces, namely a pair of maps between the respective components".

Naturality is a categorical notion, and requires being very precise about exactly what data is given – the torus as a space that happens to be a product (in the category of spaces and continuous maps) is different from the torus presented as a product (in the category of products of two spaces and continuous maps between the respective components).

[1] However, related categories (with additional structure and restrictions on the maps) do have a natural isomorphism, as described below.

However, in the absence of additional constraints (such as a requirement that maps preserve the chosen basis), the map from a space to its dual is not unique, and thus such an isomorphism requires a choice, and is "not natural".

Explicitly, for each vector space, require that it comes with the data of an isomorphism to its dual,

In other words, take as objects vector spaces with a nondegenerate bilinear form

The resulting category, with objects finite-dimensional vector spaces with a nondegenerate bilinear form, and maps linear transforms that respect the bilinear form, by construction has a natural isomorphism from the identity to the dual (each space has an isomorphism to its dual, and the maps in the category are required to commute).

Viewed in this light, this construction (add transforms for each object, restrict maps to commute with these) is completely general, and does not depend on any particular properties of vector spaces.

In this category (finite-dimensional vector spaces with a nondegenerate bilinear form, maps linear transforms that respect the bilinear form), the dual of a map between vector spaces can be identified as a transpose.

Often for reasons of geometric interest this is specialized to a subcategory, by requiring that the nondegenerate bilinear forms have additional properties, such as being symmetric (orthogonal matrices), symmetric and positive definite (inner product space), symmetric sesquilinear (Hermitian spaces), skew-symmetric and totally isotropic (symplectic vector space), etc.

– in all these categories a vector space is naturally identified with its dual, by the nondegenerate bilinear form.

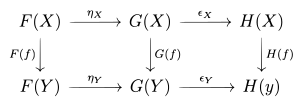

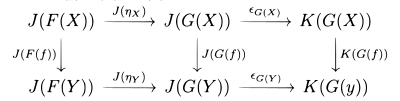

This is done componentwise: This vertical composition of natural transformations is associative and has an identity, and allows one to consider the collection of all functors

with components By using whiskering (see below), we can write hence This horizontal composition of natural transformations is also associative with identity.

[3] Whiskering is an external binary operation between a functor and a natural transformation.

Saunders Mac Lane, one of the founders of category theory, is said to have remarked, "I didn't invent categories to study functors; I invented them to study natural transformations.

The context of Mac Lane's remark was the axiomatic theory of homology.

Different ways of constructing homology could be shown to coincide: for example in the case of a simplicial complex the groups defined directly would be isomorphic to those of the singular theory.