Neanderthal

Although knowledge and perception of them has markedly changed since then in the scientific community, the image of the unevolved caveman archetype remains prevalent in popular culture.

[67] In 1856, local schoolteacher Johann Carl Fuhlrott recognised bones from Kleine Feldhofer Grotte in Neander Valley—Neanderthal 1 (the holotype specimen)—as distinct from modern humans,[e] and gave them to German anthropologist Hermann Schaaffhausen to study in 1857.

[24] Fuhlrott and Schaaffhausen met opposition namely from the prolific pathologist Rudolf Virchow who argued against defining new species based on only a single find.

French palaeontologist Marcellin Boule authored several publications, among the first to establish palaeontology as a science, detailing the specimen, but reconstructed him as slouching, ape-like, and only remotely related to modern humans.

[24][69][75] By the middle of the century, based on the exposure of Piltdown Man as a hoax as well as a reexamination of La Chapelle-aux-Saints 1 (who had osteoarthritis which caused slouching in life) and new discoveries, the scientific community began to rework its understanding of Neanderthals.

[87] A large part of the controversy stems from the vagueness of the term "species", as it is generally used to distinguish two genetically isolated populations, but admixture between modern humans and Neanderthals is known to have occurred.

Likewise, Neanderthals and Denisovans share a more recent last common ancestor (LCA) than to modern humans, based on nuclear DNA (nDNA).

The date of around 250,000 years ago cites "H. helmei" as being the last common ancestor (LCA), and the split is associated with the Levallois technique of making stone tools.

Using the latter dates, the split had likely already occurred by the time hominins spread out across Europe, and unique Neanderthal features had begun evolving by 600,000–500,000 years ago.

Pre- and early Neanderthals, on the other hand, seem to have continuously occupied only France, Spain and Italy, although some appear to have moved out of this "core-area" to form temporary settlements eastward (although without leaving Europe).

[116] The southernmost find was recorded at Shuqba Cave, Levant;[117] reports of Neanderthals from the North African Jebel Irhoud[118] and Haua Fteah[119] have been reidentified as H. sapiens.

It is possible their range expanded and contracted as the ice retreated and grew, respectively, to avoid permafrost areas, residing in certain refuge zones during glacial maxima.

[19][134] Various studies, using mtDNA analysis, yield varying effective populations,[131] such as about 1,000 to 5,000;[134] 5,000 to 9,000 remaining constant;[135] or 3,000 to 25,000 steadily increasing until 52,000 years ago before declining until extinction.

These dental traits are usually interpreted as a response to habitual heavy loading of the front teeth, either to process mechanically challenging or attritive foods, or because Neanderthals regularly used the mouth as a third hand.

[131][153] The roughly 40,000 year old Châtelperronian industry contentiously represents a culture of Neanderthals borrowing (or by process of acculturation) tool-making techniques from immigrating modern humans.

[158] As opposed to the bone sewing-needles and stitching awls found in Cro-Magnon sites, the only known Neanderthal tools that could have been used to fashion clothes are hide scrapers.

[189] Stone tools on various Greek islands could indicate early seafaring through the Mediterranean, employing simple reed boats for one-day crossings,[190] but the evidence for such a big claim is limited.

[198] One grave in Shanidar Cave, Iraq, was associated with the pollen of several flowers that may have been in bloom at the time of deposition—yarrow, centaury, ragwort, grape hyacinth, joint pine and hollyhock.

[200] The medicinal properties of the plants led American archaeologist Ralph Solecki to claim that the man buried was some leader, healer, or shaman, and that "The association of flowers with Neanderthals adds a whole new dimension to our knowledge of his humanness, indicating that he had 'soul' ".

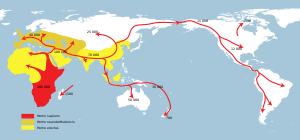

[211] Pre-agricultural Europeans appear to have had similar, or slightly higher,[209] percentages to modern East Asians, and the numbers may have decreased in the former due to dilution with a group of people which had split off before Neanderthal introgression.

[50][f] In addition, Neanderthal genes have also been implicated in the structure and function of the brain,[g] keratin filaments, sugar metabolism, muscle contraction, body fat distribution, enamel thickness and oocyte meiosis.

[96] A 2023 study confirmed that the low level of Neanderthal ancestry on the X-chromosomes is best explained by sex bias in the admixture events, and these authors also found evidence for negative selection on archaic genes.

Several Neanderthal-like fossils in Eurasia from a similar time period are often grouped into H. heidelbergensis, of which some may be relict populations of earlier humans, which could have interbred with Denisovans.

Given how few Denisovan bones are known, the discovery of a first-generation hybrid indicates interbreeding was very common between these species, and Neanderthal migration across Eurasia likely occurred sometime after 120,000 years ago.

[240] However, it is postulated that Iberian Neanderthals persisted until about 35,000 years ago, as indicated by the date range of transitional lithic assemblages—Châtelperronian, Uluzzian, Protoaurignacian and Early Aurignacian.

[11] A claim of Neanderthals surviving in a polar refuge in the Ural Mountains[124] is loosely supported by Mousterian stone tools dating to 34,000 years ago from the northern Siberian Byzovaya site at a time when modern humans may not yet have colonised the northern reaches of Europe;[126] however, modern human remains are known from the nearby Mamontovaya Kurya site dating to 40,000 years ago.

However, compared to modern humans, Neanderthals had a similar or higher genetic diversity for 12 major histocompatibility complex (MHC) genes associated with the adaptive immune system, casting doubt on this model.

[266] In late-20th-century New Guinea, due to cannibalistic funerary practices, the Fore people were decimated by transmissible spongiform encephalopathies, specifically kuru, a highly virulent disease spread by ingestion of prions found in brain tissue.

The "caveman" archetype often mocks Neanderthals and depicts them as primitive, hunchbacked, knuckle-dragging, club-wielding, grunting, nonsocial characters driven solely by animal instinct.

[23] In literature, they are sometimes depicted as brutish or monstrous, such as in H. G. Wells' The Grisly Folk and Elizabeth Marshall Thomas' The Animal Wife, but sometimes with a civilised but unfamiliar culture, as in William Golding's The Inheritors, Björn Kurtén's Dance of the Tiger, and Jean M. Auel's Clan of the Cave Bear and her Earth's Children series.