Neanderthal anatomy

Neanderthals may have had developed mesopic vision in low-light conditions, and a stronger respiratory system to fuel a comparatively faster metabolism.

Neanderthals suffered extensively from traumatic injury and major physical trauma, possibly as a consequence of risky hunting strategies and animal attacks.

Consequently, the Neanderthal skull was often anatomically compared to most notably Aboriginal Australians, who were considered the most primitive race alive.

French palaeontologist Marcellin Boule described him as a hairy, slouching, ape-like creature; a reconstruction which would endure until around the middle of the 20th century.

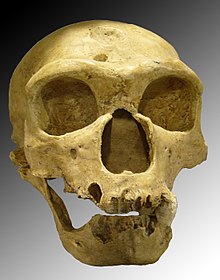

[4] Typical Neanderthal skull traits appear in the European fossil record near the beginning of the Middle Pleistocene, in specimens usually classified as H. heidelbergensis.

These "pre-Neanderthals" seem to have gradually accreted these traits ("Neanderthalization") as populations better adapted to the cold environment, evolving a "hyper-arctic" physique.

In Neanderthals, it is caused by the high and anterior (more forward) positions of the cranial base and temporal bones, in combination with a flatter skullcap.

[8] Especially in Europe, Neanderthals had a high frequency of taurodontism, a condition where the molars are bulkier due to an enlarged pulp (tooth core).

[16] The Neanderthal brain had different growth and development rates than modern humans, especially in the orbitofrontal cortex (associated with decision making), parietal and temporal lobes (language processing and memory), and the cerebellum (motor functions).

All of these regions are proportionally smaller in Neanderthals, and diverge in growth pattern at what would be a critical period in modern human neurological development.

[31] The shorter limbs, combined with evidence of a stronger respiratory system and a faster metabolism fueling more fast-twitch muscle fibres, could altogether also be explained as adaptations for sprinting.

[40] Using 76 kg (168 lb), the body mass index for Neanderthal males was calculated to be 26.9–28.2, which in modern humans correlates to being overweight.

[36] The Neanderthal LEPR gene concerned with storing fat and body heat production is similar to that of the woolly mammoth, and so was likely an adaptation for cold climate.

This may have been advantageous in northerly latitudes where daylight hours are much shorter especially in winter, and low-light or nighttime hunting would enhance ambush tactics when pursuing large game.

[24] In 1971, cognitive scientist Philip Lieberman attempted to reconstruct the Neanderthal vocal tract and concluded that it was similar to that of a modern human newborn.

He concluded that they were anatomically unable to produce the sounds /a/, /i/, /u/, /ɔ/, /g/, and /k/ and thus lacked the capacity for articulate speech, though were still able to speak at a level higher than non-human primates.

[46] Genetically, Neanderthals could carry two different variations of BNC2, which in modern populations are associated with lighter or darker skin colour in the UK Biobank.

[46] DNA analysis of three Neanderthal females from southeastern Europe indicates that they had brown eyes and dark skin colour.

[72][73] In a sample of 669 Neanderthal tooth crowns, 75% suffered some degree of enamel hypoplasia, an indicator of developmental stress perhaps caused by recurrent starvation at a young age while the teeth were forming.

[76] One extreme example is Shanidar 1, who shows signs of an amputation of the right arm likely due to a nonunion after breaking a bone in adolescence, osteomyelitis (a bone infection) on the left clavicle, an abnormal gait, vision problems in the left eye, and possible hearing loss[77] (perhaps swimmer's ear).

[78] In 1995, Trinkaus estimated that about 80% succumbed to their injuries and died before reaching 40, and thus theorised that Neanderthals employed a risky hunting strategy ("rodeo rider" hypothesis).

[83] Such intense predation probably stemmed from common confrontations due to competition over food and cave space, and from Neanderthals hunting these carnivores.

It is unknown how this affected a single Neanderthal's genetic burden and, thus, if this caused a higher rate of birth defects than in modern humans.

[84] The 13 inhabitants of Sidrón Cave collectively exhibited 17 different birth defects likely due to inbreeding or recessive disorders.

[86] Shanidar 1, who likely died at about 30 or 40, was diagnosed with the most ancient case of diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH), a degenerative disease which can restrict movement, which, if correct, would indicate a moderately high incidence rate for older Neanderthals.

[91] The leg bones of the French La Ferrassie 1 feature lesions that are consistent with periostitis—inflammation of the tissue enveloping the bone—likely a result of hypertrophic osteoarthropathy, which is primarily caused by a chest infection or lung cancer.

[88] La Chapelle-aux-Saints 1 has lesions down the length of his spine consistent with brucellosis, probably infected with Brucella abortus while butchering a carcass or eating raw meat.

[92] Neanderthals had a lower cavity rate than modern humans, despite some populations consuming typically cavity-causing foods in great quantity.

In modern humans, as an infant grows, the Eustachian tubes become angled to improve drainage of the middle ear and prevent bacterial infection.

They were exposed on two distinct occasions either by eating or drinking contaminated food or water, or inhaling lead-laced smoke from a fire.