Necrotizing fasciitis

Necrotizing fasciitis (NF), also known as flesh-eating disease, is an infection that kills the body's soft tissue.

[3] Symptoms include red or purple or black skin, swelling, severe pain, fever, and vomiting.

[3] Risk factors include recent trauma or surgery and a weakened immune system due to diabetes or cancer, obesity, alcoholism, intravenous drug use, and peripheral artery disease.

[7] Manifestations include: The initial skin changes are similar to cellulitis or abscess, so diagnosis in early stages may be difficult.

This includes but is not limited to patients with: Immunocompromised persons are twice as likely to die from necrotizing infections compared to the greater population, so higher suspicion should be maintained in this group.

[2] Vulnerable populations are typically older with medical comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus, obesity, and immunodeficiency.

[4] Other documented risk factors include: For reasons that are unclear, it can also infect healthy individuals with no previous medical history or injury.

[3] It is unclear if people with a weakened immune system would benefit from taking antibiotics after being exposed to a necrotizing infection.

[4] These bacterial species include: In polymicrobial (mixed) infections, Group A Streptococcus (S. pyogenes) is the most commonly found bacterium, followed by S.

[10] Clostridia account for 10% of overall type I infections and typically cause a specific kind of necrotizing fasciitis known as gas gangrene or myonecrosis.

Type II infection more commonly affects young, healthy adults with a history of injury.

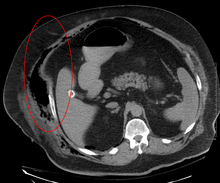

Due to the need for rapid surgical treatment, the time delay in performing imaging is a major concern.

[15] Both CT scan and MRI are used to diagnose NF, but neither are sensitive enough to rule out necrotizing changes completely.

[15] In addition, CT is helpful in evaluating complications due to NF and finding possible sources of infections.

[15] Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is considered superior to computed tomography (CT) in the visualization of soft tissues and is able to detect about 93% of NF cases.

[15] When fluid collects in the deep fascia, or thickening or enhancement with contrast, necrotizing fasciitis should be strongly suspected.

[18] It can also help rule out diagnoses that mimic earlier stages of NF, including deep vein thrombosis (DVT), superficial abscesses, and venous stasis.

[18] Findings characteristic of NF include abnormal thickening, air, or fluid in the subcutaneous tissue.

[18] The official diagnosis of NF using ultrasound requires "the presence of BOTH diffuse subcutaneous thickening AND fascial fluid more than 2 mm.

"[15] However, similar to other imaging modalities, the absence of subcutaneous free air does not definitively rule out a diagnosis of NF, because this is a finding that often emerges later in the disease process.

It may also be difficult to visualize NF over larger areas, or if there are many intervening layers of fat or muscle.

[15] Correlated with clinical findings, a white blood cell count greater than 15,000 cells/mm3 and serum sodium level less than 135 mmol/L are predictive of necrotizing fasciitis in 90% of cases.

The laboratory risk indicator for necrotizing fasciitis (LRINEC) scoring system developed by Wong and their colleagues in 2004 is the most common.

[23] This involves cutting away the skin overlying all diseased areas at the cost of increased scar formation and potential decreased quality of life post-operatively.

[23] More recently, skin-sparing debridement (SSd) has gained traction, as it resects the underlying tissue and sources of infection while preserving skin that is not overtly necrotic.

Therefore, regular dressing changes with a fecal management system can help to keep the wound at the perineal area clean.

In the case of NSTIs, empiric antibiotics are broad-spectrum, covering gram-positive (including MRSA), gram-negative, and anaerobic bacteria.

[24] Generally, antibiotics are administered until surgeons decide that no further debridement is needed, and the patient no longer shows any systemic signs of infection from a clinical and laboratory standpoint.

In 1871, Confederate States Army surgeon Joseph Jones reported 2,642 cases of hospital gangrene with a mortality rate of 46%.

[2] Despite being disfavored by the medical community, the term "galloping gangrene" was frequently used in sensationalistic news media to refer to outbreaks of necrotizing fasciitis.