Nemegtomaia

The specimen was found in a stratigraphic area that indicates Nemegtomaia preferred nesting near streams that would provide soft, sandy substrate and food.

The first specimen, MPC-D 107/15, was found by Fanti (who nicknamed it "Mary") in the Baruungoyot Formation, and consists of a nest with the presumed parent on top.

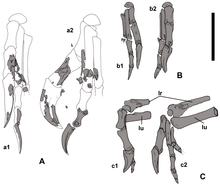

[2][5] The nesting skeleton preserves parts of the skull, both scapulae, the left arm and hand, the right humerus, the pubic bones, the ischia, the femora, the tibiae, fibulae, and the lower portions of both feet.

This specimen was found less than 500 m (1640 ft) from the holotype, and was of the same size; it was assigned to Nemegtomaia due to its similar anatomical features and geographical proximity.

[1][2][10] Though Nemegtomaia does not possess any single feature that distinguishes it from other oviraptorids (autapomorphies), the combination of a crest, an enlarged first finger, and a high number of sacral vertebrae (eight), is unique to this taxon.

The humerus (upper arm bone) had a fossa (depression) in a position similar to modern birds, but atypical among oviraptorosaurs, and appears to have been 152 mm (6 in) long.

[1][2] In their 2004 phylogenetic analysis, Lü and colleagues classified Nemegtomaia as a derived (or "advanced") oviraptorosaur, and found it to be most closely related to the genus Citipati.

[1] In 2010 Longrich and colleagues determined that Nemegtomaia belonged in the family Oviraptoridae, as part of the subfamily Ingeniinae, making it the only member of the latter group with a prominent crest.

Members of this subfamily were distinguished by smaller size, short and robust forelimbs with weakly curved claws, the number of vertebrae in the synsacrum, as well as certain features of the feet and pelvis.

Longrich and colleagues suggested that the presence of a crest on Nemegtomaia makes it possible that this feature evolved or disappeared several times among oviraptorids, or that the animal may not have been an ingeniine.

[2][14] In 2010, the American palaeontologist Gregory S. Paul suggested that crestless oviraptorids were either the juveniles or females of otherwise crested species, and that the number of genera in the group was therefore exaggerated.

[12][10] In 2012 Fanti and colleagues also found Nemegtomaia to be part of Ingeniinae as a derived member, closest to Heyuannia, due to the proportions of the hands of the two new specimens (relatively short with a robust first finger).

[16] The family Oviraptoridae (to which Nemegtomaia belongs) consisted of generally small members, and is exclusively known from the Upper Cretaceous of Asia, with most genera having been discovered in the Gobi Desert of Mongolia and China.

[2] In 2018, the Taiwanese palaeontologist Tzu-Ruei Yang and colleagues identified cuticle layers on egg-shells of maniraptoran dinosaurs, including oviraptorids.

The researchers suggested that the cuticle-coated eggs would have been a trait adapted for enhancing their reproductive success in the variable environments where Nemegtomaia and other oviraptorids nested.

It has been suggested that oviraptorosaurs as a whole were herbivores, which is supported by the gastroliths (stomach stones) found in Caudipteryx, and the wear facets in the teeth of Incisivosaurus.

In 2010 Longrich and colleagues found that oviraptorid jaws had features similar to those seen in herbivorous tetrapods (four-limbed animals), especially those of dicynodonts, an extinct group of synapsid stem-mammals.

[14] Longrich and colleagues concluded that due to the similarities between oviraptorids and herbivorous animals, the bulk of their diet would most likely have been formed by plant matter.

[14] A 2013 study by Lü and colleagues found that oviraptorids appear to have retained their hind limb proportions throughout ontogeny (growth), which is also a pattern mainly seen in herbivorous animals.

[21] In 2017, the Canadian palaeontologist Gregory F. Funston and colleagues suggested that the parrot-like jaws of oviraptorids may indicate a frugivorous diet that incorporated nuts and seeds.

[11] In 1977 Barsbold suggested that oviraptorids fed on molluscs, but Longrich and colleagues rejected the idea that they practised shell-crushing altogether, since such animals tend to have teeth with broad crushing surfaces.

The fact that most oviraptorids have been found in sediments that are interpreted as having been xeric and arid or semi-arid environments also argues against them having been specialised eaters of shellfish and eggs, as it is unlikely there would have been enough of these items under such conditions to support them.

In 2015 the Belgian palaeontologist Christophe Hendrickx and colleagues found it unlikely that Nemegtomaia and other oviraptords had bird-like kinesis in their skulls, due to the quadrate bone being immobile.

[22] Nemegtomaia is known from the Nemegt and Baruungoyot Formations, which date to the upper Campanian–lower Maastrichtian ages of the Late Cretaceous period, about 70 million years ago.

These two formations with their diverse fossils were historically thought to represent sequential time periods with different environments, but in 2009 the Canadian palaeontologist David A. Eberth and colleagues found that there was partial overlap across the transition between them.

Herbivorous dinosaurs of the Nemegt Formation include ankylosaurids such as Tarchia, the pachycephalosaurian Prenocephale, hadrosaurids such as Saurolophus and Barsboldia, and sauropods such as Nemegtosaurus, and Opisthocoelicaudia.

Other theropods include tyrannosauroids such as Tarbosaurus, Alioramus, and Bagaraatan, troodontids such as Borogovia, Tochisaurus, and Saurornithoides, therizinosaurs such as Therizinosaurus, and ornithomimosaurians such as Deinocheirus, Anserimimus, and Gallimimus.

[26][27][28] Other oviraptorosaur genera known from the Nemegt Formation include the basal Avimimus, the oviraptorids Rinchenia, Nomingia, Conchoraptor and Ajancingenia, and the caenagnathid Elmisaurus.

The Nemegt Formation is unique in having both oviraptorid and caenagnathid oviraptorosaurs, and in 1993 the Canadian palaeontologist Phillip J. Currie and colleagues suggested this diversity was due to the two groups preferring different environments in the area.

Modern skin beetles mainly feed on muscle tissue but not on moist materials, and their activity is prevented by rapid burial.