Nemi ships

Located at Nemi are the ruins of an ancient temple dedicated to Diana, which was connected by the Via Virbia to the Via Appia (the Roman road between Rome and Brindisi).

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Lord Byron, and Charles Gounod all lived in Nemi and noted the reflection of the Moon, seen in the centre of the lake during summer.

[3] Local fishermen had long been aware of the existence of the wrecks, and had explored them and removed small artefacts, often using grappling hooks to pull up pieces, which they sold to tourists.

[4] In 1446, His Eminence Prospero Cardinal Colonna and Leon Battista Alberti followed up on the stories regarding the remains and discovered them lying at a depth of 18.3 metres (60 ft), which at that time was too deep for effective salvage.

[5] His finds included bricks, marble paving stones, bronze, copper, lead artefacts, and a great number of timber beams.

[3] By 1827, interest had revived and it had become a widespread belief that earlier material recovered either had been part of a temple to Diana or was from the villa of Julius Caesar cited by Suetonius.

Felice Barnabei, director general of the Department of Antiquity and Fine Art, claimed all of the artefacts for the National Museum and submitted a report requesting the recovery cease because of the "devastation of the two wrecks".

An engineer from the Regia Marina (the Italian Royal Navy) surveyed the site to determine the feasibility of recovering the two ships intact.

[3] In 1927, Il Duce Benito Mussolini, President of the Council of Ministers, ordered Guido Ucelli [it] to drain the lake and recover the ships.

As a result of the weight reduction, on 21 August 1931, 500,000 m3 of mud erupted from the underlying strata causing 30 hectares (74 acres) of the lake floor to subside.

The topside timbers were protected by paint and tarred wool and many of their surfaces decorated with marble, mosaics, and gilded copper roof tiles.

[8] Suetonius describes two ships built for Caligula; "...ten banks of oars...the poops of which blazed with jewels...they were filled with ample baths, galleries and saloons, and supplied with a great variety of vines and fruit trees."

The superstructures appear to have been made of two main blocks of two buildings each, connected by stairs and corridors, built on raised parts of the deck at either end.

Although nothing remains of the stern and prow buildings their existence is indicated by the shorter spacing of the decks supporting cross beams and distribution of ballast.

It was argued by some that iron-tipped wooden anchors secured by ropes were not heavy enough to be effective, so they had to have metal stocks, and there was considerable academic controversy over the issue.

[12] Piston pumps (ctesibica machina: Vitruvius X.4?7) supplied the two ships with hot and cold running water via lead pipes.

[16] Conversely, an editorial released by the head of the German military office responsible for the protection of artworks (Kunstschutz) suggested that the destruction may have resulted from American artillery fire.

[17] The true responsibility for the fire remained a subject of prolonged debate, although the narrative attributing blame to German troops was widely accepted and recognized officially at an institutional level.

The analysis reveals the baselessness of the evidence against the German troops and concludes that the only plausible explanation for the fire is that it was caused by impacts from Allied artillery shells.

On the same evening as the fire, at least four explosive rounds aimed at a nearby German position accidentally struck the museum, creating significant holes in its roof.

By comparing current methodologies in fire investigation, the authors demonstrate that both the dynamics and timing of the blaze align solely with this hypothesis of accidental ignition.

The numerous contradictions and inconsistencies identified within testimonial statements and Commission documents indicate that assertions regarding German culpability constituted a convenient narrative shaped by pressures and circumstances surrounding the historical-political context of the Liberation of Italy.

Furthermore, alternative accounts concerning potential causes of the disaster proposed over time — ranging from a fire escaping control from evacuees sheltering in the museum to alleged actions by local residents, partisans, or metal thieves[20] — have proven entirely unfounded from both historiographical and factual perspectives.

In September 2017 a panel made of inlaid marble and mosaic then in the collection of a private owner in New York City was rediscovered by the antiquities restorer and author Dario del Bufalo.

Subsequently the New York County District Attorney's Office seized the artefact, which was confirmed to have come from the Nemi Museum, and to have once decorated the floor of Caligula's ship.

[21] It had been bought by two American antique dealers, Helen and Nereo Fioratti, from an aristocratic family in the late 1960s, and used since then as the surface of a coffee table in their home.

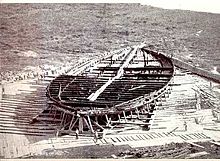

The Association initiated Project Diana, which involved constructing a full-size replica of the Roman prima nave (first ship) of Lake Nemi.

On 18 July 1998, the town council of Nemi voted to fund the construction of the forward section, and work commenced in the Torre del Greco shipyards.

[3] According to the Association Dianae Lacus website, on 15 November 2003 the large Italian employer and business confederation Assimpresa announced its immediate sponsorship of all timber required for the construction.