Neo-Riemannian theory

Neo-Riemannian theory is a loose collection of ideas present in the writings of music theorists such as David Lewin, Brian Hyer, Richard Cohn, and Henry Klumpenhouwer.

The theory is often invoked when analyzing harmonic practices within the Late Romantic period characterized by a high degree of chromaticism, including work of Schubert, Liszt, Wagner and Bruckner.

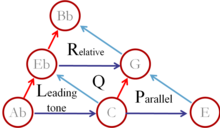

See also: Utonality) In the 1880s, Riemann proposed a system of transformations that related triads directly to each other [2] The revival of this aspect of Riemann's writings, independently of the dualist premises under which they were initially conceived, originated with David Lewin (1933–2003), particularly in his article "Amfortas's Prayer to Titurel and the Role of D in Parsifal" (1984) and his influential book, Generalized Musical Intervals and Transformations (1987).

Subsequent development in the 1990s and 2000s has expanded the scope of neo-Riemannian theory considerably, with further mathematical systematization to its basic tenets, as well as inroads into 20th century repertoires and music psychology.

Initial work in neo-Riemannian theory treated these transformations in a largely harmonic manner, without explicit attention to voice leading.

Note that here the emphasis on inversional relationships arises naturally, as a byproduct of interest in "parsimonious" voice leading, rather than being a fundamental theoretical postulate, as it was in Riemann's work.

Unlike the historical theorist for which it is named, neo-Riemannian theory typically assumes enharmonic equivalence (G♯ = A♭), which wraps the planar graph into a torus.

Richard Cohn developed the Hyper Hexatonic system to describe motion within and between separate major third cycles, all of which exhibit what he formulates as "maximal smoothness."

Many of the geometrical representations associated with neo-Riemannian theory are unified into a more general framework by the continuous voice-leading spaces explored by Clifton Callender, Ian Quinn, and Dmitri Tymoczko.

[7][11] Finally, Callender, Quinn, and Tymoczko together proposed a unified framework connecting these and many other geometrical spaces representing diverse range of music-theoretical properties.

Another recent continuous version of the Tonnetz — simultaneously in original and dual form — is the Torus of phases[14] which enables even finer analyses, for instance in early romantic music.

The geometries to which voice-leading proximity give rise attain central status, and the transformations become heuristic labels for certain kinds of standard routines, rather than their defining property.