Infant mortality

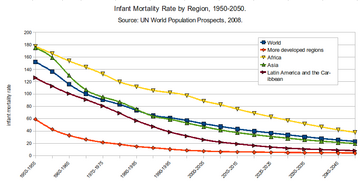

[8] Improving sanitation, access to clean drinking water, immunization against infectious diseases, and other public health measures can help reduce rates of infant mortality.

[citation needed] Biomarkers of inflammation, including C-reactive protein, ferritin, various interleukins, chemokines, cytokines, defensins, and bacteria, have been shown to be associated with increased risks of infection or inflammation-related preterm birth.

[35] The United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report SIDS to be the leading cause of death in infants aged one month to one year of life.

[37] Though the exact cause is unknown, the "triple-risk model" presents three factors that together may contribute to SIDS: smoking while pregnant, the age of the infant, and stress from conditions such as prone sleeping, co-sleeping, overheating, and covering of the face or head.

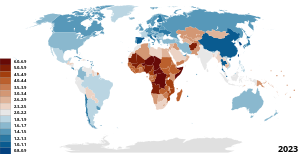

[44] According to the New England Journal of Medicine, "in the past two decades, the infant mortality rate (deaths under one year of age per thousand live births) in the United States has declined sharply.

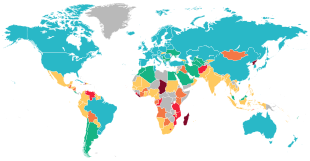

[58] Developing nations with democratic governments tend to be more responsive to public opinion, social movements, and special interest groups on issues like infant mortality.

[59] If the nation's ability to raise its own revenues is compromised, governments will lose funding for their health service programs, including those that aim to decrease infant mortality rates.

[47] According to the Journal of the American Medical Association, "the post neonatal mortality risk (28 to 364 days) was highest among continental Puerto Ricans" compared to non-Hispanic babies.

[93] According to UNICEF, hand washing with soap before eating and after using the toilet can save children's lives by reducing deaths from diarrhea and acute respiratory infections.

[94] Focusing on preventing preterm and low birth weight deliveries throughout all populations can help eliminate cases of infant mortality and decrease health care disparities within communities.

[7] Many countries have instituted mandatory folic acid supplementation in their food supply, which has significantly reduced the occurrence of a birth defect known as spina bifida in newborns.

[110] Similarly, coordinated efforts to train community health workers in diagnosis, treatment, malnutrition prevention, reporting and referral services has reduced infant mortality in children under 5 by as much as 38%.

[111] Public health campaigns centered around the First 1000 days of life have been successful in providing cost-effective supplemental nutrition programs, as well as assisting young mothers in sanitation, hygiene and breastfeeding.

[21] The World Health Organization (WHO) defines a live birth as any infant born demonstrating independent signs of life, including breathing, heartbeat, umbilical cord pulsation or definite movement of voluntary muscles.

This point is reinforced by the demographer Ansley Coale, who finds the high ratios of reported stillbirths to infant deaths in Hong Kong and Japan in the first 24 hours after birth dubious.

Many countries, including the United States, Sweden and Germany, count any birth exhibiting any sign of life as alive, no matter the month of gestation or neonatal size.

[129][130][131] However, differences in reporting are unlikely to be the primary explanation for the high rate of infant mortality in the United States compared to countries at a similar level of economic development.

Access to vital registry systems for infant births and deaths is an extremely difficult and expensive task for poor parents living in rural areas.

Little has been done to address the underlying structural problems with the vital registry systems regarding the lack of reporting in rural areas, which has created a gap between the official and popular meanings of child death.

However there remain barriers that affect the validity of statistics of infant mortality, including political economic decisions: numbers are exaggerated when international funds are being doled out; and underestimated during reelection.

"[154] A study in North Carolina, for example, concluded that "white women who did not complete high school have a lower infant mortality rate than black college graduates.

"[155] Likewise, dozens of population-based studies indicate that "the subjective, or perceived experience of racial discrimination is strongly associated with an increased risk of infant death and with poor health prospects for future generations of African Americans.

[156] While the popular argument is that due to the trend of black women being of a lower socio-economic status there is in an increased likelihood of a child suffering, and while this does correlate, the theory is not congruent with the data on Latino IMR in the United States.

Tyan Parker Dominguez at the University of Southern California offers a theory to explain the disproportionally high IMR among black women in the United States.

[159] Mary O. Hearst, a professor in the Department of Public Health at Saint Catherine University, researched the effects of segregation on the African American community to see if it contributed to the high IMR in black children.

Racism, economic disparities, and sexism in segregated communities are all examples of the daily stressors that pregnant black women face, and are risk factors for conditions that can affect their pregnancies such as pre-eclampsia and hypertension.

Others argue that increasing diversity in the health care industry can help reduce the IMR as more representation can tackle deep-rooted racial biases and stereotypes that exist towards African American women.

[163] It was in the early 1900s when countries around the world started to notice that there was a need for better child health care services; first in Europe, and then with the United States creating a campaign to decrease the infant mortality rate.

[176] These factors, on top of a general increase in the standard of living in urban areas, helped the United States make dramatic improvements to their rates of infant mortality in the early 20th century.

Additionally, economic realities and long-held cultural factors incentivized male offspring, leading some families who already had sons to avoid prenatal care or professional delivery services, and causing China to have unusually high female infant mortality rates during this time.