Network tap

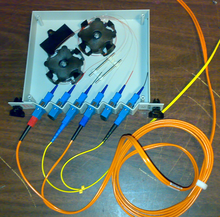

A tap is typically a dedicated hardware device, which provides a way to access the data flowing across a computer network.

Taps are used in security applications because they are non-obtrusive, are not detectable on the network (having no physical or logical address), can deal with full-duplex and non-shared networks, and will usually pass through or bypass traffic even if the tap stops working or loses power.

All of the "vendor terms" are common within the industry, have real definitions and are valuable points of consideration when buying a tap device.

The simplest type of monitoring is logging into an interesting device and running programs or commands that show performance statistics and other data.

Many vendors have alleviated this by using intelligent polling schedulers, but this may still affect the performance of the device being monitored.

This tapping method consists in enabling promiscuous mode on the device that is used for the monitoring and attaching it to a network hub.

The "victim" device might stop receiving traffic when the tapping-device is updating/rebooting if said mechanisms weren't integrated in a smart way (aka.

One way this can work, for fiber-based network technologies, is that the tap divides the incoming light using a simple physical apparatus into two outputs, one for the pass-through, one for the monitor.

Modern network technologies are often full-duplex, meaning that data can travel in both directions at the same time.

Other monitoring technologies, such as passive fiber network TAPs do not deal well with the full-duplex traffic.

This scenario is for active, inline security tools, such as next-generation fire walls, intrusion prevention systems and web application firewalls.

This means that they can work with most data link network technologies that use that physical media, such as ATM and some forms of Ethernet.

Some taps can also reproduce low-level network errors, such as short frames, bad CRC or corrupted data.

Network taps can require channel bonding on monitoring devices to get around the problem with full-duplex discussed above.

[3] Even so, a short disruption is preferable to taking a network down multiple times to deploy a monitoring tool.

Another counter-measure is to deploy a fiber-optic sensor into the existing raceway, conduit or armored cable.

In this scenario, anyone attempting to physically access the data (copper or fiber infrastructure) is detected by the alarm system.

A small number of alarm systems manufacturers provide a simple way to monitor the optical fiber for physical intrusion disturbances.

There is also a proven solution that utilizes existing dark (unused) fiber in a multi-strand cable for the purpose of creating an alarm system.

In the alarmed cable scenario, the sensing mechanism uses optical interferometry in which modally dispersive coherent light traveling through the multi-mode fiber mixes at the fiber's terminus, resulting in a characteristic pattern of light and dark splotches called speckle.

A fiber-optic sensor works by measuring the time dependence of this speckle pattern and applying digital signal processing to the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) of the temporal data.

7003, Protective Distribution Systems (PDS), provides guidance for the protection of SIPRNET wire line and optical fiber PDS to transmit unencrypted classified National Security Information (NSI).

The 1000BASE-T signal uses PAM 5 modulation, meaning that each cable pair transports 5 bits simultaneously in both directions.

The PHY chips at each end of the cable have a very complex task at hand, because they must separate the two signals from each other.