Neutrino oscillation

[1] First predicted by Bruno Pontecorvo in 1957,[2][3] neutrino oscillation has since been observed by a multitude of experiments in several different contexts.

In particular, it implies that the neutrino has a non-zero mass outside the Einstein-Cartan torsion,[4][5] which requires a modification to the Standard Model of particle physics.

[7] The 2015 Nobel Prize in Physics was shared by Takaaki Kajita and Arthur B. McDonald for their early pioneering observations of these oscillations.

The first experiment that detected the effects of neutrino oscillation was Ray Davis' Homestake experiment in the late 1960s, in which he observed a deficit in the flux of solar neutrinos with respect to the prediction of the Standard Solar Model, using a chlorine-based detector.

[1] Following the theories that were proposed in the 1970s suggesting unification of electromagnetic, weak, and strong forces, a few experiments on proton decay followed in the 1980s.

Mikaelyan and Sinev proposed to use two identical detectors to cancel systematic uncertainties in reactor experiment to measure the parameter θ13.

The MINOS, K2K, and Super-K experiments have all independently observed muon neutrino disappearance over such long baselines.

[1] In 2010, the INFN and CERN announced the observation of a tauon particle in a muon neutrino beam in the OPERA detector located at Gran Sasso, 730 km away from the source in Geneva.

The electron flavor content of the neutrino will then continue to oscillate – as long as the quantum mechanical state maintains coherence.

No analogous mechanism exists in the Standard Model that would make charged leptons detectably oscillate.

The case of (real) W boson decay is more complicated: W boson decay is sufficiently energetic to generate a charged lepton that is not in a mass eigenstate; however, the charged lepton would lose coherence, if it had any, over interatomic distances (0.1 nm) and would thus quickly cease any meaningful oscillation.

Therefore, detection of a charged lepton oscillation from W boson decay is infeasible on multiple levels.

[19][20] The idea of neutrino oscillation was first put forward in 1957 by Bruno Pontecorvo, who proposed that neutrino–antineutrino transitions may occur in analogy with neutral kaon mixing.

[24] In its simplest form it is expressed as a unitary transformation relating the flavor and mass eigenbasis and can be written as where The symbol

The phase factor δ is non-zero only if neutrino oscillation violates CP symmetry; this has not yet been observed experimentally.

are mass eigenstates, their propagation can be described by plane wave solutions of the form where In the ultrarelativistic limit,

This limit applies to all practical (currently observed) neutrinos, since their masses are less than 1 eV and their energies are at least 1 MeV, so the Lorentz factor, γ, is greater than 106 in all cases.

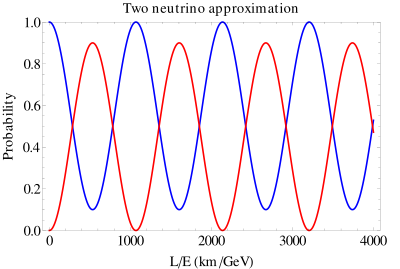

In this case, it is sufficient to consider the mixing matrix Then the probability of a neutrino changing its flavor is Or, using SI units and the convention introduced above This formula is often appropriate for discussing the transition νμ ↔ ντ in atmospheric mixing, since the electron neutrino plays almost no role in this case.

These are the parameters that are most easily produced and detected (in the case of neutrinos, by weak interactions involving the W boson).

With two pendulums (labeled a and b) of equal mass but possibly unequal lengths and connected by a spring, the total potential energy is This is a quadratic form in xa and xb, which can also be written as a matrix product: The 2×2 matrix is real symmetric and so (by the spectral theorem) it is orthogonally diagonalizable.

This requires the introduction of complex phases in addition to the rotation angles, which are associated with CP violation but do not influence the observable effects of neutrino oscillation.

The graphs below show the probabilities for each flavor, with the plots in the left column showing a long range to display the slow "solar" oscillation, and the plots in the right column zoomed in, to display the fast "atmospheric" oscillation.

From atmospheric and solar neutrino oscillation experiments, it is known that two mixing angles of the MNS matrix are large and the third is smaller.

These new neutrinos would interact with the other fermions solely in this way and hence would not be directly observable, so are not phenomenologically excluded.

The most popular conjectured solution currently is the seesaw mechanism, where right-handed neutrinos with very large Majorana masses are added.

If it is assumed that the neutrinos interact with the Higgs field with approximately the same strengths as the charged fermions do, the heavy mass should be close to the GUT scale.

[31] The addition of right-handed neutrinos has the effect of adding new mass scales, unrelated to the mass scale of the Standard Model, hence the observation of heavy right-handed neutrinos would reveal physics beyond the Standard Model.

There are alternative ways to modify the standard model that are similar to the addition of heavy right-handed neutrinos (e.g., the addition of new scalars or fermions in triplet states) and other modifications that are less similar (e.g., neutrino masses from loop effects and/or from suppressed couplings).

There, the exchange of supersymmetric particles such as squarks and sleptons can break the lepton number and lead to neutrino masses.

During the early universe when particle concentrations and temperatures were high, neutrino oscillations could have behaved differently.