New Forest

[14] Like much of England, the site of the New Forest was once deciduous woodland, recolonised by birch and eventually beech and oak after the withdrawal of the ice sheets starting around 12,000 years ago.

[15] There was still a significant amount of woodland in this part of Britain, but this was gradually reduced, particularly towards the end of the Middle Iron Age around 250–100 BC, and most importantly the 12th and 13th centuries, and of this essentially all that remains today is the New Forest.

[18] One may be the only known inhumation site of the Early Iron Age and the only known Hallstatt culture burial place in Britain, though any bodies are likely decomposed beyond detection by the acidic soil.

Twelfth-century chroniclers alleged that William had created the forest by evicting the inhabitants of 36 parishes, reducing a flourishing district to a wasteland; this account is thought dubious by most historians, as the poor soil in much of the area is believed to have been incapable of supporting large-scale agriculture, and significant areas appear to have always been uninhabited.

Though many claim the latter is due to an inaccurate arrow shot from his hunting companion, local folklore asserted that this was punishment for the crimes committed by William when he created his New Forest; 17th-century writer Richard Blome provides detail: In this County [Hantshire] is New-Forest, formerly called Ytene, being about 30 miles in compass; in which said tract William the Conqueror (for the making of the said Forest a harbour for Wild-beasts for his Game) caused 36 Parish Churches, with all the Houses thereto belonging, to be pulled down, and the poor Inhabitants left succourless of house or home.

But this wicked act did not long go unpunished, for his Sons felt the smart thereof; Richard being blasted with a pestilent Air; Rufus shot through with an Arrow; and Henry his Grand-child, by Robert his eldest son, as he pursued his Game, was hanged among the boughs, and so dyed.

Felling of broadleaved trees, and their replacement by conifers, began during the First World War to meet the wartime demand for wood.

In 2005, a special exhibition was mounted at the estate, with a video showing photographs from that era as well as voice recordings of former SOE trainers and agents.

Grazing of Commoners' ponies and cattle is an essential part of the management of the forest, helping to maintain the heathland, bog, grassland and wood-pasture habitats and their associated wildlife.

Recently this ancient practice has come under pressure as houses that benefit from forest rights pass to owners with no interest in commoning.

Existing families with a new generation heavily rely on inheritance of, rather than the (mostly expensive) purchase of, a benefiting house with paddock or farm.

Commoners marking animals for grazing can claim about £200 per cow per year, and about £160 for a pony, and more if participating in the stewardship scheme.

With 10 cattle and 40 ponies, a Commoner qualifying for both schemes would receive over £8,000 a year, and more if they also put out pigs: net of marking fees, feed and veterinary costs this part-time level of involvement across a family is calculated to give an annual income in the thousands of pounds in most years.

The ecological value of the New Forest is enhanced by the relatively large areas of lowland habitats, lost elsewhere, which have survived.

[43] The Forest is an important stronghold for a rich variety of fungi, and although these have been heavily gathered in the past, there are control measures now in place to manage this.

Specialist heathland birds are widespread, including Dartford warbler (Curruca undata), woodlark (Lullula arborea), northern lapwing (Vanellus vanellus), Eurasian curlew (Numenius arquata), European nightjar (Caprimulgus europaeus), Eurasian hobby (Falco subbuteo), European stonechat (Saxicola rubecola), common redstart (Phoenicurus phoenicurus) and tree pipit (Anthus sylvestris).

Woodland birds include wood warbler (Phylloscopus sibilatrix), stock dove (Columba oenas), European honey buzzard (Pernis apivorus) and northern goshawk (Accipiter gentilis).

Birds seen more rarely include red kite (Milvus milvus), wintering great grey shrike (Lanius exubitor) and hen harrier (Circus cyaneus) and migrating ring ouzel (Turdus torquatus) and northern wheatear (Oenanthe oenanthe).

A programme to reintroduce the sand lizard (Lacerta agilis) started in 1989[46] and the great crested newt (Triturus cristatus) already breeds in many locations.

Cattle are of various breeds, most commonly Galloways and their crossbreeds, but also various other hardy types such as Highlands, Herefords, Dexters, Kerries and British whites.

The pigs used for pannage, during the autumn months, are now of various breeds, but the New Forest was the original home of the Wessex Saddleback, now extinct in Britain.

Numerous deer live in the Forest; they are usually rather shy and tend to stay out of sight when people are around, but are surprisingly bold at night, even when a car drives past.

[49] The red squirrel (Sciurus vulgaris) survived in the Forest until the 1970s – longer than most places in lowland Britain (though it still occurs on the Isle of Wight and the nearby Brownsea Island).

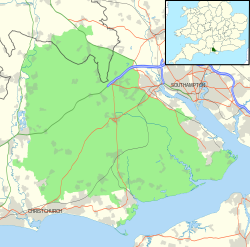

Outside of the National Park Area in New Forest District, several clusters of larger towns frame the area – Totton and the Waterside settlements (Marchwood, Dibden, Hythe, Fawley) to the East, Christchurch, New Milton, Milford on Sea, and Lymington to the South, and Fordingbridge and Ringwood to the West.

An order to create the park was made by the Agency on 24 January 2002 and submitted to the Secretary of State for confirmation in February 2002.

Following objections from seven local authorities and others, a public inquiry was held from 8 October 2002 to 10 April 2003, and concluded by endorsing the proposal with some detailed changes to the boundary of the area to be designated.

[citation needed] On 28 June 2004, Rural Affairs Minister Alun Michael confirmed the government's intention to designate the area as a National Park, with further detailed boundary adjustments.

The total area of land initially proposed for inclusion but ultimately left out of the Park is around 120 km2 (46 sq mi).

There is an allusion to the foundation of the New Forest in an end-rhyming poem found in the Peterborough Chronicle's entry for 1087, The Rime of King William.

Oberon, Titania and the other Shakespearean fairies live in a rapidly diminishing Sherwood Forest whittled away by urban development in the fantasy novel A Midsummer's Nightmare by Garry Kilworth.