Newgrange

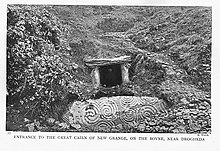

Newgrange (Irish: Sí an Bhrú[1]) is a prehistoric monument in County Meath in Ireland, located on a rise overlooking the River Boyne, eight kilometres (five miles) west of the town of Drogheda.

Newgrange is the main monument in the Brú na Bóinne complex, a World Heritage Site that also includes the passage tombs of Knowth and Dowth, as well as other henges, burial mounds and standing stones.

Newgrange is a popular tourist site and, according to archaeologist Colin Renfrew, is "unhesitatingly regarded by the prehistorian as the great national monument of Ireland" and as one of the most important megalithic structures in Europe.

[14] These carvings fit into ten categories, five of which are curvilinear (circles, spirals, arcs, serpentiniforms, and dot-in-circles) and the other five of which are rectilinear (chevrons, lozenges, radials, parallel lines, and offsets).

The Neolithic people who built the monument were native agriculturalists, growing crops and raising animals such as cattle in the area where their settlements were located.

[19] According to carbon-14 dates,[20] it is approximately 500 years older than the current form of Stonehenge and the Great Pyramid of Giza in Egypt, as well as predating the Mycenaean culture of ancient Greece.

[24] Frank Mitchell suggested that the monument could have been built within a space of five years, basing his estimation upon the likely number of local inhabitants during the Neolithic and the amount of time they could have devoted to building it rather than farming.

[29] Many more artifacts had been found in the passage in previous centuries by visiting antiquarians and tourists, although most of these were removed and went missing or held in private collections.

[30] The remains of animals also have been found in the structure, primarily those of mountain hares, rabbits, and dogs, but also of bats, sheep, goats, cattle, song thrushes, and more rarely, molluscs and frogs.

[31] DNA analysis found that bones deposited in the most elaborate chamber belonged to a man whose parents were first-degree relatives, possibly brother and sister.

[33][34] However, archaeologist Alasdair Whittle said that social difference in the Neolithic was often short-lived, speculating that an elite may have arisen temporarily in response to crisis.

"[36] O'Kelly believed that Newgrange, alongside the hundreds of other passage tombs built in Ireland during the Neolithic, showed evidence for a religion that venerated the dead as one of its core principles.

He believed that this "cult of the dead" was just one particular form of European Neolithic religion, and that other megalithic monuments displayed evidence for different religious beliefs that were solar-oriented, rather than ancestor-oriented.

[36] Studies in other fields of expertise offer alternative interpretations of the possible functions, however, which principally centre on the astronomy, engineering, geometry, and mythology associated with the Boyne monuments.

This view is strengthened by the discovery of alignments in Knowth, Dowth, and the Lough Crew Cairns leading to the interpretation of these monuments as calendrical or astronomical devices.

[39] The solar alignment at Newgrange is very precise compared to similar phenomena at other passage graves such as Dowth or Maes Howe in the Orkney Islands, off the coast of Scotland.

[47] It has been suggested that this tale represents the winter solstice illumination of Newgrange, during which the sunbeam (the Dagda) enters the inner chamber (the womb of Boann) when the sun's path stands still.

[49] This tale has also been linked with recent DNA analysis, which found that a man buried at Newgrange had parents who were most likely siblings (see #Construction and burials).

Newgrange is not mentioned in any of the early charters of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, but an Inspeximus granted by Edward III in 1348 includes a Nova Grangia among the demesne lands of the abbey.

[54] In 1699, the local landowner, Williamite settler Charles Campbell,[55] ordered some of his farm labourers to dig up a part of Newgrange, which then had the appearance of a large mound of earth, so that he could collect stone from within it.

The labourers soon discovered the entrance to the tomb within the mound, and a Welsh antiquarian named Edward Lhwyd, who was staying in the area, was alerted and took an interest in the monument.

He talked to Charles Campbell, who informed him that he had found the remains of two human corpses in the tomb, one (which was male) in one of the cisterns and another farther along the passageway, something that Lhwyd had not noted.

In 1890, under the leadership of Thomas Newenham Deane, the board began a project of conservation of the monument, which had been damaged through general deterioration over the previous three millennia as well as the increasing vandalism caused by visitors, some of whom had inscribed their names on the stones.

[63] For 60 years in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century Annie (d. 1964) and Bob Hickey looked after Newgrange as caretakers, custodians and tour guides following his appointment c. 1890.

[68] The height of the original façade was calculated as being up to 3 meters tall by civil engineer John Fogarty of University College Cork, an expert on the movement of piled-up loose materials.

[70] As part of the restoration, this white quartz façade was rebuilt, and a concrete support wall built behind it in case of a future cairn collapse.

[73][74] Other archaeologists have supported O'Kelly's conclusions and the reconstructed façade, such as Robert Hensey and Elizabeth Shee Twohig in their paper "Facing the cairn at Newgrange" (2017), where they set forth the archaeological evidence.

[75] Along with archaeologist Carleton Jones,[76] Hensey and Twohig note that passage tombs in Brittany have similar near-vertical dry stone fronts, such as Gavrinis and Barnenez.

[78] This claim was refuted by several prominent Irish archaeologists, including Prof William O'Brien and Ann Lynch, who noted that it has been recorded photographically since the early 1900s, and in detailed site drawings from the excavation.

[81] Current-day visitors to Newgrange are treated to a guided tour and a re-enactment of the Winter Solstice experience through the use of high-powered electric lights situated within the tomb.