New Objectivity

The term was coined by Gustav Friedrich Hartlaub, the director of the Kunsthalle in Mannheim, who used it as the title of an art exhibition staged in 1925 to showcase artists who were working in a post-expressionist spirit.

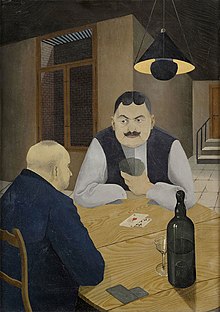

Rather than some goal of philosophical objectivity, it was meant to imply a turn towards practical engagement with the world—an all-business attitude, understood by Germans as intrinsically American.

The idea that it conveys resignation comes from the notion that the age of great socialist revolutions was over and that the left-leaning intellectuals who were living in Germany at the time wanted to adapt themselves to the social order represented in the Weimar Republic.

Expressionism was in particular the dominant form of art in Germany, and it was represented in many different facets of public life—in dance, in theater, in painting, in architecture, in poetry, and in literature.

Expressionists abandoned nature and sought to express emotional experience, often centering their art around inner turmoil (angst), whether in reaction to the modern world, to alienation from society, or in the creation of personal identity.

The early exponents of Dada had been drawn together in Switzerland, a neutral country in the war, and seeing their common cause, wanted to use their art as a form of moral and cultural protest—they saw shaking off the constraints of artistic language in the same way they saw their refusal of national boundaries.

Throughout Europe a return to order in the arts resulted in neoclassical works by modernists such as Picasso and Stravinsky, and a turn away from abstraction by many artists, for example Matisse and Metzinger.

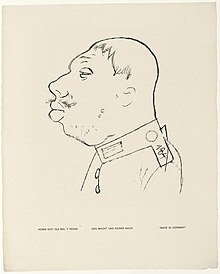

[8] The verists developed Dada's abandonment of any pictorial rules or artistic language into a “satirical hyperrealism”, as termed by Raoul Hausmann, and of which the best known examples are the graphical works and photo-montages of John Heartfield.

Artists active in Hanover, such as Grethe Jürgens, Hans Mertens, Ernst Thoms, and Erich Wegner, depicted provincial subject matter with an often lyrical style.

[19] Albert Renger-Patzsch and August Sander are leading representatives of the "New Photography" movement, which brought a sharply focused, documentary quality to the photographic art where previously the self-consciously poetic had held sway.

Architects such as Bruno Taut, Erich Mendelsohn and Hans Poelzig turned to New Objectivity's straightforward, functionally minded, matter-of-fact approach to construction, which became known in Germany as Neues Bauen ("New Building").

As a cinematic style, it translated into realistic settings, straightforward camerawork and editing, a tendency to examine inanimate objects as a way to interpret characters and events, a lack of overt emotionalism, and social themes.

Composer Paul Hindemith may be considered both a New Objectivist and an expressionist, depending on the composition, throughout the 1920s; for example, his wind quintet Kleine Kammermusik Op.

2 (1922) was designed as Gebrauchsmusik; one may compare his operas Sancta Susanna (part of an expressionist trilogy) and Neues vom Tage (a parody of modern life).

[25] His music typically harkens back to baroque models and makes use of traditional forms and stable polyphonic structures, together with modern dissonance and jazz-inflected rhythms.

The New Objectivity movement is usually considered to have ended with the Weimar Republic when the National Socialists under Adolf Hitler seized power in January 1933.

George Grosz emigrated to America and adopted a romantic style, and Max Beckmann's work by the time he left Germany in 1937 was, by Franz Roh's definitions, expressionism.