New Orleans Mint

After it was decommissioned as a mint, the building has served a variety of purposes, including as an assay office, a United States Coast Guard storage facility, and a fallout shelter.

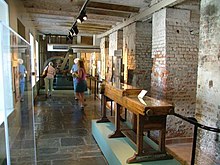

The center includes collections of colonial-era manuscripts and maps, and primary and secondary source materials in a wide range of media.

[8] The establishment of the New Orleans Mint was prompted by a complex fiscal crisis of the 1830s, which included a general shortage of domestically-minted coinage and the frequent circulation of foreign coins to alleviate the problem.

In 1836 Jackson had issued an executive order called the Specie Circular which demanded that all land transactions in the United States be conducted in cash.

Both of these actions, combined with the economic depression following the Panic of 1837 (caused partly by Jackson's fiscal policies) increased the domestic need for minted money.

New Orleans was selected because of the city's strategic location along the Mississippi River which made it a vitally important center for commercial activity, including the export of cotton from the area's plantations.

While the Philadelphia Mint produced a substantial quantity of coinage, in the early 19th century it could not disperse the money swiftly to the far regions of the new nation, particularly the South and West.

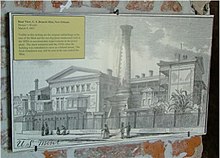

[16] On the north façade the mint building features a central projecting Ionic portico, supported by four monumental columns that are flanked at the ends by square pillars.

"[17] On the interior, Strickland placed the grand staircase that connects the three levels immediately behind the portico in the central core of the structure.

The floor system is composed of fired-clay jack arches supported on steel I-beams, a common feature of warehouses and other long-span structures.

On the second floor, many of the larger rooms, which were used for coining and melting, contain ceilings with beautiful high arches supported by the walls and freestanding piers.

The smaller rectangular rooms on the second level (and the basement), such as the former superintendent's office, also contain these arched ceilings with a single groin vault.

In 1854, the federal government hired West Point engineering graduate (and Louisiana native) Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard to fireproof the building, rebuild the arches supporting the basement ceiling and install masonry flooring.

During this period, the Mint's heavy machinery was converted to steam power so a smokestack (since demolished) was built at the rear of the structure to carry away the fumes.

[19] Less than two years later, Beauregard would rise to national fame as the Confederate general who ordered the April 1861 assault on Fort Sumter in Charleston harbor, South Carolina, thus beginning the American Civil War.

One was John Leonard Riddell, who served as melter and refiner at the Mint from 1839 to 1848, and, outside of his job, pursued interests in botany, medicine, chemistry, geology, and physics.

He also wrote on numismatics, publishing in 1845 a book entitled Monograph of the Silver Dollar, Good and Bad, Illustrated With Facsimile Figures, and two years later an article by him appeared in DeBow's Review called "The Mint at New Orleans—Processes Pursued of Working the Precious Metals—Statistics of Coinage, etc."

Riddell was not held in high esteem by everyone, however: his conflicts with other Mint employees were well-documented, and at one point he was accused of being unable to properly conduct a gold melt.

Articles discussing and images picturing the Mint, in addition to the one by Riddell noted above, were featured in Ballou's Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion, published in Boston, and the widely circulated Harper's Weekly.

[25] Research suggests that 1861-O half dollars bearing a bisected date die crack ("WB-103") and 1861-O half-dollars with a "speared olive bud" anomaly ("WB-104") on the reverse had been minted under authority of the Confederacy.

The exact number of the half-dollar coins struck by the Confederate mint with the alternate reverse is unknown; but only four are known to exist today.

[27] After that the mint was used for quartering Confederate troops, until it was recaptured along with the rest of the city the following year, largely by Union naval forces under the command of Admiral David Farragut.

[27] The event stuck in the minds of many New Orleanians: eleven years later, in 1873, a visitor to the city named Edward King mentioned it in his description of the structure.

[29] The refurbishment and recommissioning of the New Orleans Mint was due partly to the fact that in 1878 the Federal government in Washington, D.C. had passed the Bland–Allison Act, which mandated the purchase and coining of a large quantity of silver yearly.

It reopened the New Orleans facility primarily to coin large quantities of silver dollars, most of which were simply stored in the building instead of circulated.

On July 3, 1885, President Cleveland appointed Gabriel Montegut, a native of New Orleans and resident of Terrebonne Parish to head the Mint.

These women would sit at long narrow tables, filing the planchets down to the proper weight, wearing special aprons with pouches attached to the sleeves and the waist to catch the excess dust.

In a circular distributed by his campaign to the citizens of New Orleans, Long listed the loss of the Mint as the very first of many complaints against Ransdell's lengthy service record in the Senate.

The Coast Guard then took over the building as a nominal storage facility, though in truth the structure was largely abandoned and left to decay until it was transferred to the state of Louisiana in 1965.

Along with the Cabildo, the Presbytere, the 1850 House, and Madame John's Legacy, this facility is one of five branches of the Louisiana State Museum in the French Quarter.