New Year's Day March

In February 1959, Richard Henry, an African American civilian Air Force employee, planned to fly out of the Greenville, South Carolina Municipal Airport to Michigan.

With the assistance of the NAACP, Henry filed a suit claiming discrimination and the denial of the equal protection clause granted by the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

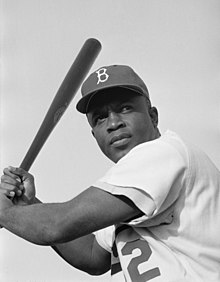

[3] On the morning of October 25, 1959, Jackie Robinson, the first African American Major League Baseball player, was expected to speak at an NAACP banquet at Springfield Baptist Church in downtown Greenville.

Robinson spoke of this discrimination at the banquet, and he urged "complete freedom" by encouraging all African Americans to vote, to protest racial inequality, and to never lose self-respect.

Marshall, however, dismissed Robinson's plea as a "waste of time;" he noted that Richard Henry's case was still working its way through the federal court system.

"[1] January 1st was chosen specifically as it marked the 97th anniversary of President Abraham Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation, which attempted to free slaves in Confederate states in 1863.

Alice Spearman, the executive director of the South Carolina Council on Human Relations, remarked that this was the first time that any government in a Southern state used police to protect black protesters.

[14] However, while Hollings did facilitate the desegregation of public facilities, he noted in his directive to send police to protect marchers that he wanted the government to enforce the law, not "rednecks" or "members of the Klan.

Since the news of the march had been publicized prior to the event, when protesters arrived at the airport, they were greeted by a 300-man white crowd, including members of the Ku Klux Klan.

A delegation of fifteen African American ministers entered the airport on behalf of the protesters where they prayed for "their enemies" and read a resolution.

That our insistence upon the right to participate fully in the democratic processes of our nation is an expression of our patriotism and not a defection to some foreign ideology.

That with faith in this nation and its God we shall not relent, we shall not rest, we shall not compromise, we shall not be satisfied until every vestige of racial discrimination and segregation has been eliminated from all aspects of our public life.

Additionally, seeing the brutality that erupted in other states, such as Alabama and Mississippi, leaders in Greenville and South Carolina sought to desegregate relatively quickly.

Judge George Timmerman, a former South Carolina governor that opposed Brown v. Board of Education (1954) and federally-mandated segregation, ruled in favor of the airport.

Timmerman, citing Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), which had already been overturned by Brown v. Board (1954), wrote that no law or constitutional principle "requires others to accept [Henry] as a companion or social equal.

Senator from South Carolina, unexpectedly admitted that the separation of races was a policy that needed to be changed: “The desegregation issue cannot continue to be hidden behind the door.

We must handle this ourselves, more realistically than heretofore"[18] Furthermore, Governor Fritz Hollings' endeavor to integrate schools "with dignity" meant that South Carolina was often out of the national spotlight when desegregation began.