New Zealand Company

[5] Only 15,500 settlers arrived in New Zealand as part of the company's colonisation schemes, but three of its settlements would, along with Auckland, become and remain the country's "main centres" and provide the foundation for the system of provincial government introduced in 1853.

[11] On 5 March 1826 the ships, Lambton and Rosanna, reached Stewart Island, which Herd explored and then dismissed as a possible settlement, before sailing north to inspect land around Otago Harbour.

Herd explored the area and identified land at the south-west of the harbour as the best place for a European settlement, ignoring the presence of a large pā that was home to members of Te Āti Awa tribe.

In 1829 Wakefield began publishing pamphlets and writing newspaper articles that were reprinted in a book, promoting the concept of systematic emigration to Australasia through a commercial profit-making enterprise.

[15] Wakefield's plan entailed a company buying land from the indigenous residents of Australia or New Zealand very cheaply, then selling it to speculators and "gentleman settlers" for a much higher sum.

[17] Despite the £20,000 loss incurred in his earlier venture, Lambton (from the 1830s known as Lord Durham) continued to pursue ways to become involved in commercial emigration schemes and was joined in his endeavours by Radical MPs Charles Buller and Sir William Molesworth.

The Whig government in 1834 passed an Act authorising the establishment of the British Province of South Australia, but the planning and initial sales of land proceeded without Wakefield's involvement because of the illness and death of his daughter.

Parliamentary Under-Secretary for the colonies Lord Howick and Permanent Under-Secretary James Stephen both were concerned about proposals for the settlements' founders to make laws for the colony, fearing it would create a dynasty beyond British government control,[20] while Anglican and Wesleyan missionaries were alarmed by claims made in pamphlets written by Wakefield in which he declared that one of the aims of colonisation was to "civilise a barbarous people" who could "scarcely cultivate the earth".

[21] At a meeting on 6 June 1837 the Church Missionary Society passed four resolutions expressing its objection to the New Zealand Association plans, including the observation that previous experience had shown that European colonisation invariably inflicted grave injuries and injustices on the indigenous inhabitants.

Three weeks after the Bill's defeat, the New Zealand Association held its final meeting and passed a resolution to the effect that "notwithstanding this temporary failure", members would persevere with their efforts to establish "a well-regulated system of colonization".

Chaired by Lord Petre, the company was to have paid-up capital of £25,000 in 50 shares of £50, and declared its purpose was "the purchase and sale of lands, the promotion of emigration, and the establishment of public works".

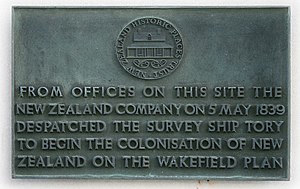

In August the Cuba, with a surveyors' team headed by Captain William Mein Smith, R.A., set sail, and a month later—still with no word on the success of the Tory and Cuba—on 15 September 1839 it was followed from Gravesend, London, by the Oriental,[39] the first of five 500-ton immigrant ships hired by the company.

Following the Oriental were the Aurora, Adelaide, Duke of Roxburgh and Bengal Merchant, plus a freight vessel, the Glenbervie,[40] which all sailed with instructions to rendezvous on 10 January 1840 at Port Hardy on d'Urville Island where they would be told of their final destination.

He was told to seek land for settlements where there were safe harbours that would foster export trade, rivers allowing passage to fertile inland property, and waterfalls that could power industry.

He was told the company was eager to acquire land around harbours on both sides of Cook Strait and that while Port Nicholson appeared the best site he should also closely examine Queen Charlotte Sound and Cloudy Bay at the north of the South Island.

[42] Wakefield was told: You will readily explain that after English emigration and settlement a tenth of the land will be far more valuable than the whole was before ... the intention of the Company is not to make reserves for the Native owners in large blocks, as has been the common practice as to Indian reserves in North America, whereby settlement is impeded, and the savages are encouraged to continue savage, living apart from the civilized community ... instead of a barren possession with which they have parted, they will have a property in land intermixed with the property of civilised and industrious settlers and made really valuable by that circumstance.

[47] On 8 November in Queen Charlotte Sound he secured the signature of an exiled Taranaki chief, Wiremu Kīngi Te Rangitāke, and 31 others for land[48] whose description was near-identical to that of the Kapiti deal.

Under instructions from the Colonial Office, Hobson was to set up a system in which much of the revenue raised from the sale of land to settlers would be used to cover the costs of administration and development, but a portion of the funds would also be used to send emigrants to New Zealand.

He learned of their bid to imprison a Captain Pearson of the barque Integrity and that on 2 March they had raised the flag of the United Tribes of New Zealand at Port Nicholson,[59][60] proclaiming government by "colonial council" that claimed to derive its powers from authority granted by local chiefs.

[69] Surveyors quickly encountered problems, however, when they discovered the land selected for the new settlement was still inhabited by Māori, who expressed astonishment and bewilderment to find Pākehā tramping through their homes, gardens and cemeteries and driving wooden survey pegs into the ground.

[70] Wakefield had purchased the land during a frantic week-long campaign the previous September, with payment made in the form of iron pots, soap, guns, ammunition, axes, fish hooks, clothing—including red nightcaps—slates, pencils, umbrellas, sealing wax and jaw harps.

[74] In line with his instructions, Wakefield promised local Māori they would be given reserves of land equal to one-tenth of the area, with their allotments chosen by lottery and sprinkled among the European settlers.

Although settlers in Nelson and Wellington were appalled at the slaughter at Wairau, an investigation by Governor Robert FitzRoy laid the blame squarely at the feet of the New Zealand Company representatives.

The party of German migrants on the St Pauli, with 140 passengers including John Beit, the "overbearing and arrogant, greedy, untruthful" New Zealand Company agent in Hamburg, went to Nelson instead.

[91][92][93] In a bid to restore certainty to the settlers over their land claims a three-man deputation was sent to Sydney to meet Gipps; in early December the deputation returned with news that Gipps would procure for the Wellington settlers a confirmation of their titles to 110,000 acres of land, as well as their town, subject to several conditions including that the 110,000 acres were taken in one continuous block, native reserves were guaranteed and that reserves were made for public purposes.

The decision outraged settlers, who were aware of friction with returning Māori, but had been hoping the Governor would station a body of troops at New Plymouth or sanction the formation of a militia to protect their land.

[110] In July 1843 the New Zealand Company issued a prospectus for the sale of 120,550 acres (48,000 hectares), divided between town, suburban and rural lots at a new settlement called New Edinburgh.

The company worked with the Lay Association of the Free Church of Scotland on the sale of, and ballot for, land and the first body of settlers sailed for what became the settlement of Dunedin in late November 1847.

The colonising efforts were taken up by the Canterbury Association, Gibbon Wakefield's new project, and the New Zealand Company became a silent partner in the settlement process, providing little more than the initial purchase funds.

[114] The company, in its final report in May 1858, conceded it had erred, but said the communities they had planted had now assumed "gratifying proportions" and they could look forward to the day when "New Zealand shall take her place as the offspring and counterpart of her Parent Isle ... the Britain of the Southern Hemisphere."