Cultural racism

The concept of cultural racism was developed in the 1980s and 1990s by West European scholars such as Martin Barker, Étienne Balibar, and Pierre-André Taguieff.

These theorists argued that the hostility to immigrants then evident in Western countries should be labelled racism, a term that had been used to describe discrimination on the grounds of perceived biological race since the early 20th century.

One is that hostility on a cultural basis can result in the same discriminatory and harmful practices as belief in intrinsic biological differences, such as exploitation, oppression, or extermination.

Influenced by critical pedagogy, those calling for the eradication of cultural racism in Western countries have largely argued that this should be done by promoting multicultural education and anti-racism through schools and universities.

[14] Following the Second World War, when Nazi Germany was defeated and biologists developed the science of genetics, the idea that the human species sub-divided into biologically distinct races began to decline.

Such a view is clearly based on the assumption that certain groups are the genuine carriers of the national culture and the exclusive heirs of their history while others are potential slayers of its 'purity'.

This holds that categories like "migrants" and "Muslims" have—despite not representing biologically united groups—undergone a process of "racialization" in that they have come to be regarded as unitary groups on the basis of shared cultural traits.

"[38] He suggested that beliefs which insist that group identification require the adoption of cultural traits such as specific dress, language, custom, and religion might better be termed ethnicism or ethnocentrism and that when these also incorporate hostility to foreigners they may be described as bordering on xenophobia.

[38] He does however acknowledge that "it is possible to talk of ‘cultural racism’ despite the fact that strictly speaking modern ideas of race have always had one or other biological foundation.

Thus, the racist elements of any particular proposition can only be judged by understanding the general context of public and private discourses in which ethnicity, national identifications, and race coexist in blurred and overlapping forms without clear demarcations.

Similarly, Siebers and Dennissen questioned whether bringing "together the exclusion/oppression of groups as different as current migrants in Europe, Afro-Americans and Latinos in the US, Jews in the Holocaust and in the Spanish Reconquista, slaves and indigenous peoples in the Spanish Conquista and so on into the concept of racism, irrespective of justifications, does the concept not run the risk of losing in historical precision and pertinence what it gains in universality?

[45] In addition, she suggested that, despite its emphasis on culture, early work on "neo-racism" still betrayed its focus on biological differences by devoting its attention to black people—however defined—and neglecting the experiences of lighter-skinned ethnic minorities in Britain, such as Jews, Romanis, the Irish, and Cypriots.

[49] Wren argued that cultural racism had manifested in a largely similar way throughout Europe, but with specific variations in different places according to the established ideas of national identity and the form and timing of immigration.

[51] Based on fieldwork in the country during 1995, she argued that cultural racism had encouraged anti-immigration sentiment throughout Danish society and generated "various forms of racist practice", including housing quotas that restrict the number of ethnic minorities to around 10%.

[55] The sociologist Xolela Mangcu argued that cultural racism could be seen as a contributing factor in the construction of apartheid, a system of racial segregation that privileged whites, in South Africa during the latter 1940s.

He noted that the Dutch-born South African politician Hendrik Verwoerd, a prominent figure in establishing the apartheid system, had argued in favour of separating racial groups on the grounds of cultural difference.

[59] In the early 1990s, the scholar of critical pedagogy Henry Giroux argued that cultural racism was evident across the political right in the United States.

[60] For Giroux, the conservative administration of President George H. W. Bush acknowledged the presence of racial and ethnic diversity in the U.S., but presented it as a threat to national unity.

[48] Similarly, in 2000 Powell suggested that cultural racism underpinned many of the policies and decisions made by U.S. educational institutions, although often on an "unconscious level".

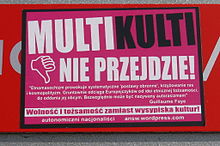

[67] The scholar of English Daniel Wollenberg stated that in the latter part of the 20th century and early decades of the 21st, many in the European far-right began to distance themselves from the biological racism that characterised neo-Nazi and neo-fascist groups and instead emphasised "culture and heritage" as the "key factors in constructing communal identity".

[68] The previous political failures of the domestic terrorist group Organisation Armée Secrète during the Algerian War (1954–62), along with the electoral defeat of far-right candidate Jean-Louis Tixier-Vignancour in the 1965 French presidential election, led to the adoption of a meta-political strategy of 'cultural hegemony' within the nascent Nouvelle Droite (ND).

[69] GRECE, an ethno-nationalist think-thank founded in 1968 to influence established right-wing political parties and diffuse ND ideas within the society at large, advised its members "to abandon an outdated language" by 1969.

[71] During the 1980s, this tactic was adopted by France's National Front (FN) party, which was then growing in support under the leadership of Jean-Marie Le Pen.

[73] In Denmark, a far-right group called the Den Danske Forening (The Danish Society) was launched in 1986, presenting arguments about cultural incompatibility aimed largely at refugees entering the country.

[76] For instance, a range of academics studying the English Defence League, an Islamophobic street protest organisation founded in London in 2009, have labelled it culturally racist.

[83][84] Martin Hewitt, the chair of the National Police Chiefs' Council, warned that implementing that definition could exacerbate community tensions and hamper counter-terrorist efforts against Salafi jihadism.

[87] In 1999, Flecha argued that the main approach to anti-racist education adopted in Europe had been a "relativistic" one that emphasised diversity and difference between ethnic groups – the same basic message promoted by cultural racism.

[88] Flecha expressed the view that to combat cultural racism, anti-racists should instead utilise a "dialogic" approach which encourages different ethnic groups to live alongside each other according to rules that they have all agreed upon through a "free and egalitarian dialogue".

[89] Wollenberg commented that those radical right-wing groups which emphasise cultural difference had converted "multiculturalist anti-racism into a tool of racism".

[94] Specifically, he urged teachers to provide their students with the "analytic tools" through which they could learn to challenge accounts that perpetuated ethnocentric discourses and thus "racism, sexism and colonialism".