Newburgh Conspiracy

The Newburgh Conspiracy was a failed apparent threat by leaders of the Continental Army in March 1783, at the end of the American Revolutionary War.

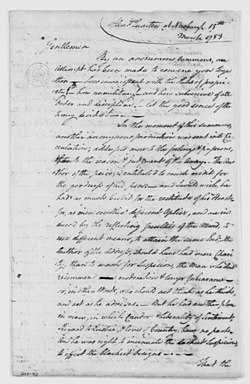

The letter was said to have been written by Major John Armstrong, aide to General Horatio Gates, although the authorship and underlying ideas are subjects of historical debate.

Commander-in-Chief George Washington stopped any serious talk of rebellion when he made an emotional address to his officers asking them to support the supremacy of Congress.

With the end of the war and dissolution of the Continental Army approaching, soldiers who had long been unpaid feared that the Confederation Congress would not meet previous promises concerning back pay and pensions.

[1] Financier Robert Morris had in early 1782 stopped army pay as a cost-saving measure, arguing that when the war finally ended the arrears would be made up.

It first met with Robert Morris, who stated that there were no funds to meet the army's demands, and that loans for government operations would require evidence of a revenue stream.

[13] When it met with McDougall on January 13, the general painted a stark picture of the discontent at Newburgh; Colonel Brooks opined that "a disappointment might throw [the army] into blind extremities.

"[14] When Congress met on January 22 to debate the committee's report, Robert Morris shocked the body by tendering his resignation, heightening tension.

Four days later, Colonel Brooks was dispatched back to Newburgh with instructions to gain the army leadership's agreement with the proposed nationalist plan.

On February 12, McDougall sent a letter (signed with the pseudonym Brutus) to General Knox suggesting that the army might have to mutiny by refusing to disband until it was paid.

"[16] Historian Richard Kohn is of the opinion that the purpose of these communications was not to foment a coup or military action against Congress or the states, but to use the specter of a recalcitrant army's refusal to disband as a political weapon against the antinationalists.

[18] Alexander Hamilton wrote a letter to General Washington the same day, essentially warning him of the possibility of impending unrest among the ranks, and urging him to "take the direction" of the army's anger.

[20] It was unclear to the Congressional nationalists whether Knox, who had been a regular supporter of army protests to Congress, would play a role in any sort of staged action.

In letters written February 21, Knox unambiguously indicated he would play no such part, expressing the hope that the army's force would only be used against "the Enemies of the liberties in America.

Approved by virtually the entire assembly, the resolution expressed "unshaken confidence" in Congress, and "disdain" and "abhorrence" for the irregular proposals published earlier in the week.

[33] The only voice raised in opposition was that of Colonel Timothy Pickering, who criticized members of the assembly for hypocritically condemning the anonymous addresses that only days before they had been praising.

[34] Nationalist leaders orchestrated the creation of a committee to respond to the news, which was deliberately populated with members opposed to any sort of pension payment.

The pressure worked on Connecticut representative Eliphalet Dyer, one of the committee members, and he proposed approval of a lump sum payment on March 20.

Due in part to a critical miscommunication, troops in eastern Pennsylvania were led to believe that they would be discharged even before Morris' promissory notes would be distributed, and they marched to the city in protest.

Pennsylvania President John Dickinson refused to call out the militia (reasoning they might actually support the mutineers), and Congress decided to relocate to Princeton, New Jersey.

There is circumstantial evidence that several participants in the Newburgh affair (notably Walter Stewart, John Armstrong, and Gouverneur Morris) may have played a role in this uprising as well.

Grant's 1832 pension application stated that during the Revolutionary War he had escaped from his enslaver, a Loyalist from New England, so that he would not be compelled to serve in the British forces.

[41][40] The main long-term result of the Newburgh affair was a strong reaffirmation of the principle of civilian control of the military, and banishing any possibility of a coup as outside the realm of republican values.

[45] Historian C. Edward Skeen writes that Kohn's case is weak because it relies heavily on interpretation of written statements and is not well supported by the actions of the alleged conspirators.

If Head discounts the conspiracy of legend, he makes clear that the disputes over officers’ pay and pensions threatened the legitimacy of the Confederation Congress and the balance of state and federal power, and that Washington sought to protect both. "