Newcastle & Carlisle Railway

It is situated on the River Eden at the head of the Solway Firth, but both those waterways suffered from shoaling and sandbanks, frustrating the potential for maritime traffic.

A prospectus and public invitation to subscribe was published on 28 March[4] The first meeting of the provisional Newcastle upon Tyne and Carlisle Rail-Road Company met on 9 April 1825; James Losh was elected chairman.

[5]Plans for the line were submitted for a parliamentary bill in the 1826 session, but before any hearing determined opposition was experienced from two landed proprietors on the route, as well as from George Howard, 6th Earl of Carlisle, who had extensive colliery interests near Brampton, and did not wish his near-monopoly to be disrupted.

The originally designed line between Carlisle and Gilsland had followed the Irthing Valley, but the new scheme took it south of that route on to high ground, requiring more challenging engineering features.

There were considerable difficulties in the parliamentary process, particularly over levels, bridge clearances and construction, and resilience to flooding, but the Newcastle-upon-Tyne and Carlisle Railway Act 1829 (10 Geo.

[1][7][8][2] In fact the supporters of the alternative route on the south of the Tyne, to Gateshead, continued their fight; the advantage of it was the comparative ease of reaching the section of the Tyne further east where sea-going ships could berth; mineral traffic from points on the line to shipping quays was a prime consideration, and a north-bank railway could not reach this location without extreme engineering difficulty.

The revised route at the Carlisle end of the line was now uncontroversial, although it involved prodigious engineering works, including several viaducts and large bridges, and a tunnel.

)[1] The controversy over the route at the eastern end continued and on 10 September 1833, the board decided to alter it to follow the south bank, to a terminus at Redheugh, at Askew's Quay, a little east of the location of the present King Edward VII bridge.

In addition, it was now urgently desired to extend to deeper water east of Gateshead and a separate company was founded with the encouragement of the N&CR, to build that line.

The route was expected to require two rope-worked inclined planes, to climb from near Redheugh to the high ground of Gateshead, and then again to descend to the Tyne at Hebburn.

[10] The BG&HR hesitated, and in May 1835 had just begun work as the Brandling brothers announced plans to build a railway from Gateshead to South Shields and Monkwearmouth.

The Brandling Junction Railway was formed on 5 September, and it was agreed in the negotiations that followed that the N&CR would take over and extend the BG&HR from the Derwent through to Gateshead.

The difficulty increased at the end of 1832 when Giles failed to forecast costs of completion of the line consistently, or to explain the inconsistency, or to attend board meetings.

On 13 June, therefore, the board of the N&CR decided to adopt the same arrangement and subsequently placed orders for two locomotives, of which one was to be built by R & W Hawthorn Ltd. and the other by Robert Stephenson & Co.

The GNER planned to approach through Low Fell, that is on an alignment similar to the present main line from Durham, but at a lower level to reach the N&CR Redheugh bridge.

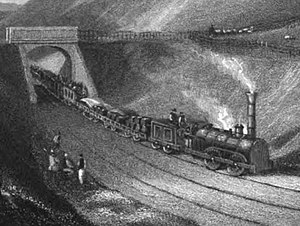

[28] These early railway steam locomotives had no brakes, although some tenders were fitted with them,[29] and there were no weatherboards, the driver and firemen wearing moleskin suits for protection.

The Brandling Junction Railway was under construction, rising by a steep incline (at 1 in 22) to cross Gateshead on viaduct and descend again to the Tyne on the east side of the town; it opened on 15 January 1839.

At the time there was almost no building east of the present-day Gateshead Highway (A167) and an incline to the bank of the Tyne ran south to north through the site now occupied by the Sage.

[j] The intention was still to extend into the centre of Newcastle, but indecision continued over the location, a tunnelled route to the Spital being put forward, as well as a terminus near the Infirmary (west of Forth Banks).

[36] The latter took some years to complete; the architect John Dobson designed it to a Doric classical style with a trainshed roof constructed of three 60 feet (18 m) wide bays.

This proved a catastrophic deal for the NBR, as the Hexham route was impossibly circuitous and difficult, whereas the NER now ran all east coast main line trains, passenger and goods, through to Edinburgh.

[42] The Beaumont Lead Company was operating at Allendale, 12 miles east of Alston, and it too suffered heavy transport costs in conveying its output to the railway, at Haydon Bridge.

Until 1844, the line between Stocksfield and Hexham and between Rosehill and Milton was a single track but, in that year, the directors doubled these portions of the railway in preparation for the increase of traffic anticipated from the opening of the Newcastle and Darlington Junction Railway, at the same time enlarging the Farnley Tunnel near Corbridge—a work accomplished without stopping the running of the trains except for a few days subsequent to 28 December 1844, when a portion of the old roof was damaged and the loose sand above it slid down and blocked the line.

Hudson's clear intention was to get a through line to Edinburgh, and he made public plans to cross the Tyne from Gateshead, and to build a common station in Newcastle.

The resulting agreement was effective from 1 August 1848, and the YN&BR leased the Maryport and Carlisle line too, intending to operate them as a single entity.

In fact serious revelations about George Hudson's shady business methods emerged at this time, and the findings of the resulting committees of enquiry among his many companies were so damaging that he was unable to continue in his leadership role.

[63] However two shareholders obtained a Court of Chancery judgment in July 1859 that the agreement had exceeded the companies' powers, and they resumed independent, although collaborative, operation.

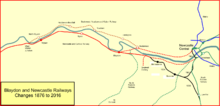

[15] In the early days of planning the route of the Newcastle and Carlisle Railway, opinion had been voiced in favour of running on the north bank of the Tyne west of Lemington and Newburn.

It left the line from Carlisle to the west of Wylam and crossed the Tyne there, running east on the north bank and rejoining the N&CR at Scotswood; the capital was £85,000.

The Wetheral Viaduct known locally as Corby Bridge, and crossing the River Eden is listed Grade I; it consists of five semi-circular stone arches of 80 feet span.