Nichiren

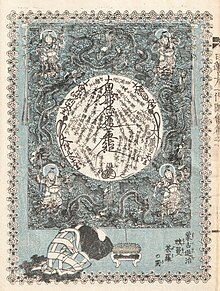

[11] He advocated the repeated recitation of its title, Nam(u)-myoho-renge-kyo, as the only path to Buddhahood and held that Shakyamuni Buddha and all other Buddhist deities were extraordinary manifestations of a particular Buddha-nature termed Myoho-Renge that is equally accessible to all.

In the final stage of this twenty-year period he traveled to Mount Kōya, the center of Shingon esoteric Buddhism, and to Nara where he studied its six established schools, especially the Ritsu sect which emphasized strict monastic discipline.

[41]: 233 This declaration also marks the start of his efforts to make profound Buddhist theory practical and actionable so an ordinary person could manifest Buddhahood within his or her own lifetime in the midst of day-to-day realities.

[57]: 246–247 [28]: 6–7 Nichiren then developed a base of operation in Kamakura where he converted several Tendai priests, directly ordained others, and attracted lay disciples who were drawn mainly from the strata of the lower and middle samurai class.

[57]: 432#49 Nichiren sought scriptural references to explain the unfolding of natural disasters and then wrote a series of works which, based on the Buddhist theory of the non-duality of the human mind and the environment, attributed the sufferings to the weakened spiritual condition of people, thereby causing the Kami (protective forces or traces of the Buddha) to abandon the nation.

In it he argued the necessity for "the Sovereign to recognize and accept the singly true and correct form of Buddhism (i.e., 立正 risshō) as the only way to achieve peace and prosperity for the land and its people and end their suffering (i.e., 安国 ankoku).

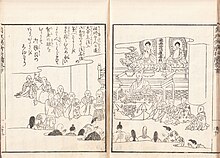

"[61][62][63] Using a dialectic form well-established in China and Japan, the treatise is a 10-segment fictional dialogue between a Buddhist wise man, presumably Nichiren, and a visitor who together lament the tragedies that have beleaguered the nation.

The wise man answers the guest's questions and, after a heated exchange, gradually leads him to enthusiastically embrace the vision of a country grounded firmly on the ideals of the Lotus Sutra.

Nichiren began to emphasize the purpose of human existence as being the practice of the bodhisattva ideal in the real world which entails undertaking struggle and manifesting endurance.

In a series of letters to prominent leaders he directly provoked the major prelates of Kamakura temples that the Hojo family patronized, criticized the principles of Zen which was popular among the samurai class, critiqued the esoteric practices of Shingon just as the government was invoking them, and condemned the ideas underlying Risshū as it was enjoying a revival.

In September 1271, after a fiery exchange of letters between the two, Nichiren was arrested by a band of soldiers and tried by Hei no Saemon (平の左衛門, also called 平頼綱 Taira no Yoritsuna), the deputy chief of the Hojo clan's Board of Retainers.

Apparently a majority of his disciples abandoned their faith and others questioned why they and Nichiren were facing such adversity in light of the Lotus Sutra's promise of "peace and security in the present life.

[57]: 261 During his self-imposed exile at Mount Minobu, a location 100 miles west of Kamakura,[77][78][79] Nichiren led a widespread movement of followers in Kanto and Sado mainly through his prolific letter-writing.

The scope of his thinking was outlined in an essay Hokke Shuyō-shō (法華取要抄, "Choosing the Heart of the Lotus Sutra"), considered by Nikkō Shōnin as one of Nichiren's ten major writings.

[94][74]: 251 [95][96]: 54 Some of his religious thinking was derived from the Tendai understanding of the Lotus Sutra, syncretic beliefs that were deeply rooted in the culture of his times, and new perspectives that were products of Kamakura Buddhism.

According to Nichiren these phenomena manifest when a person chants the title of the Lotus Sutra (date) and shares its validity with others, even at the cost of one's life if need be.

[103] Although Nichiren attributed the turmoils and disasters in society to the widespread practice of what he deemed inferior Buddhist teachings that were under government sponsorship, he was enthusiastically upbeat about the portent of the age.

He asserted, in contrast to other Mahayana schools, this was the best possible moment to be alive, the era in which the Lotus Sutra was to spread, and the time in which the Bodhisattvas of the Earth would appear to propagate it.

[30]: 114–115 Hōnen, in turn, employed harsh polemics instructing people to "discard" (捨, sha), "close" (閉, hei), "put aside" (閣, kaku), and "abandon" (抛, hō) the Lotus Sutra and other non-Pure Land teachings.

[30]: 114, 145–146 At age 32, Nichiren began a career of denouncing other Mahayana Buddhist schools of his time and declaring what he asserted was the correct teaching, the Universal Dharma (Nam(u)-Myōhō-Renge-Kyō), and chanting its words as the only path for both personal and social salvation.

[119][120] By extension, he argued, through proper prayer and action his troubled society would transform into an ideal world in which peace and wisdom prevail and "the wind will not thrash the branches nor the rain fall hard enough to break clods.

They are the quality of the teaching (kyō), the innate human capacity (ki) of the people, the time (ji), the characteristic of the land or country (koku), and the sequence of dharma propagation (kyōhō rufu no zengo).

He held that Zen was devilish in its belief that attaining enlightenment was possible without relying on the Buddha's words; Ritsu was thievery because it hid behind token deeds such as public works.

[40]: 8–11 [125][126] Nichiren deemed the world to be in a degenerative age and believed that people required a simple and effective means to rediscover the core of Buddhism and thereby restore their spirits and times.

[127]: 354 Nichiren describes the first two secret laws in numerous other writings but the reference to the platform of ordination appears only in the Sandai Hiho Sho, a work whose authenticity has been questioned by some scholars.

[138]: 34, 36 In letters to some of his followers Nichiren extended the concept of meeting persecution for the sake of propagating the Dharma to experiencing tribulations in life such as problems with family discord or illness.

[138]: 37 Naturally, he did not use language redolent of twentieth century concepts within, e.g., psychotherapy, hyperliberalism or the Human Potential Movement, but his insistence on personal responsibility can be reimagined in such terms.

He express that his resolve to carry out his mission was paramount in importance and that the Lotus Sutra's promise of a peaceful and secure existence meant finding joy and validation in the process of overcoming karma.

According to Stone, in confronting karma Nichiren "demonstrated an attitude that wastes little energy in railing against it but unflinchingly embraces it, interpreting it in whatever way appears meaningful at the moment so as to use that suffering for one's own development and to offer it on behalf of others.

[164] In these letters Nichiren plays particular attention to the instantaneous attainment of enlightenment of the Dragon King's daughter in the "Devadatta" (Twelfth) chapter of the Lotus Sutra and displays deep concern for the fears and worries of his female disciples.