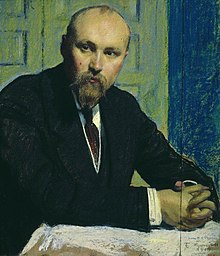

Nicholas Roerich

[1][2] Born in Saint Petersburg, to a well-to-do Baltic German father and to a Russian mother,[3] Roerich lived in various places in the world until his death in Naggar, India.

[5] The so-called Roerich Pact (for the protection of cultural objects) was signed into law by the United States and most other nations of the Pan-American Union in April 1935.

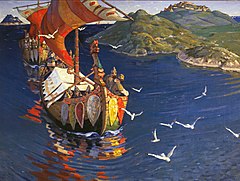

Artistically, Roerich became known as his generation's most talented painter of Russia's ancient past, a topic that was compatible with his lifelong interest in archeology.

He also designed religious art for places of worship throughout Russia and Ukraine, most notably the Queen of Heaven fresco for the Church of the Holy Spirit, which the patroness Maria Tenisheva built near her Talashkino estate, and the stained glass windows for the Datsan Gunzechoinei in 1913–1915.

[9] During the first decade of the 1900s and in the early 1910s, Roerich, largely by the influence of his wife, Helena, developed an interest in eastern religions, as well as alternative belief systems such as Theosophy.

Both Roerichs became avid readers of the Vedantist essays of Ramakrishna and Vivekananda, the poetry of Rabindranath Tagore, and the Bhagavad Gita.

Both attempted to gain the attention of the Provisional Government and Petrograd Soviet on the need to form a coherent cultural policy and, most urgently, to protect art and architecture from destruction and vandalism.

After the October Revolution and the acquisition of power of Lenin's Bolshevik Party, Roerich became increasingly discouraged about Russia's political future.

It seems that Roerich was a preferred choice to manage its department of artistic education; the topic is rendered moot by the fact that the Soviets elected not to establish such a commissariat.

However, Roerich had an amply-documented extreme hostility to the Bolshevik regime, prompted not so much by a dislike of communism as by his revulsion at Lenin's ruthlessness and his fear that Bolshevism would result in the destruction of Russia's artistic and architectural heritage.

While in London, Roerich also contributed scenic designs for LAHDA, a cooperative group of Russian theatrical artists led by Theodore Komisarjevsky.

Roerich befriended acclaimed soprano Mary Garden of the Chicago Opera and received a commission to design a 1922 production of Rimsky-Korsakov's The Snow Maiden for her.

That led him to formulate his "Great Plan," which envisaged the unification of millions of Asian peoples through a religious movement using the Future Buddha, or Maitreya, into a "Second Union of the East."

There, the King of Shambhala would, following the Maitreya prophecies, make his appearance to fight a great battle against all evil forces on Earth.

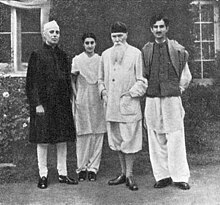

Roerich spent his time painting the Himalayas with visitors such as Frederick Marshman Bailey, Lady Emily Bulwer-Lytton, and members of the 1924 British Everest Expedition, as well as Sonam Wangfel Laden La, Kusho Doring, and Tsarong Shape, influential Tibetans.

It was during his stay in the Himalayas that Roerich learned about the flight of the 9th Panchen Lama, which he interpreted as the fulfillment of the Matreiya prophecies and the bringing about of the Age of Shambhala.

On his way to America, Roerich stopped at the Soviet embassy in Berlin, where he told the local plenipotentiary about a Central Asian expedition he wanted to take.

Roerich commented on the "occupation of Tibet by the British" by claiming that they "infiltrate in small parties... conduct extensive anti-Soviet propaganda" by talking about "anti-religious activity of the Bolsheviks."

The plenipotentiary later pointed out to one of Roerich's old university classmates, Georgy Chicherin, that he had "absolutely pro-Soviet leanings, which looked somewhat Buddho-Communistic," and that his son, who spoke 28 Asian languages, helped him in gaining the favor with the Indians and the Tibetans.

They founded several institutions during these years: Cor Ardens ("Flaming Heart") and Corona Mundi ("Crown of the World"), both of which were meant to unite artists around the globe in the cause of civic activism; the Master Institute of United Arts, an art school with a versatile curriculum, and the eventual home of the first Nicholas Roerich Museum; and an American Agni Yoga Society.

His work for this cause also resulted in the United States and the 20 other nations of the Pan-American Union signing the Roerich Pact, an early international instrument protecting cultural property, on April 15, 1935 at the White House.

Roerich was in India during World War II, where he painted Russian epic heroic and saintly themes, including Alexander Nevsky, The Fight of Mstislav and Rededia, and Boris and Gleb.

Its active participants were Ernest Hemingway, Rockwell Kent, Charlie Chaplin, Emil Cooper, Serge Koussevitzky, and Valeriy Ivanovich Tereshchenko.

[35] Roerich's biography and his controversial expeditions to Tibet and Manchuria have been examined recently by a number of authors, including two Russians, Vladimir Rosov and Alexandre Andreyev, two Americans (Andrei Znamenski and John McCannon), and the German Ernst von Waldenfels.

[36] A series of his studies on the Himalayan Ranges-donated by the artist's son (36 works specifically) are even showcased in the Nicholas Roerich Gallery of the Karnataka Chitrakala Parishath Museum based in Bangalore, India.

The hypnotic, immersive nature of his works truly absorbs the onlooker, leaving one with a sense of peace and tranquility as one moves with the series through the gallery.