Nicholas of Worcester

Nicholas carried on this work as prior, and he was highly respected by the leading chroniclers, William of Malmesbury, John of Worcester and Eadmer, who acknowledged his assistance in their histories.

[3] The historian Emma Mason writes that Wulfstan "played an important role in the transmission of Old English cultural and religious values to the Anglo-Norman world".

[6] In his Vita Wulfstani (Life of Wulfstan), the twelfth-century historian William of Malmesbury wrote: "On his English side, Nicholas was of exalted descent.

[12] The historian Eadmer, who was a friend of Nicholas, mentions as one of his sources for his Life of Dunstan, an Æthelred who was sub-prior of Canterbury and later a dignitary of the Worcester church.

[15] The identification of Nicholas with Æthelred is also accepted by the medievalists Ann Williams and Patrick Wormald,[16] but the theory is disputed by the historian of religion David Knowles because Eadmer stated that Æthelred had earlier served for a long time under Bishop Æthelric of Selsey, who died in 1038, and Nicholas would have been too young for the association with Æthelric and a senior position at Canterbury.

Nicholas lost his remaining hair around the time that Wulfstan died, and Mason comments that whereas the modern reader would see progressive baldness, the twelfth century saw the success of a minor prophecy.

[26] The historians Emma Mason and Julia Barrow suggest that Nicholas was probably involved in the production of the fraudulent Altitonantis, which purported to be a contemporary record of the establishment of monasticism at Worcester by Oswald in the 960s.

[29] In Mason's view, Wulfstan probably authorised the production of Altitonantis in order to support legal claims by the monastic community for which they had no genuine documentary evidence.

[30] The monks of Canterbury carried out a programme of forgery in the 1070s purporting to show that privileges claimed for the archbishopric had an ancient origin, and Mason comments that Nicholas may have brought back from his stay there "innovative, not to say imaginative, techniques in the drafting of charters".

[35] Bishop Samson of Worcester had died on 5 May 1112, and King Henry I nominated Theulf as his successor on 28 December 1113, but as the archbishopric of Canterbury was then vacant he was not consecrated until 27 June 1115, when Archbishop Ralph d'Escures received his pallium from Rome and was thus empowered to perform the ceremony.

William wrote: Wulfstan's long survival after the Norman Conquest allowed him to inculcate the values of English monasticism into the first wave of French monks in Worcester, and his work was carried on by Nicholas during his time as prior.

And, something I think particularly to his credit, he so inculcated letters into the occupants of the place, by both teaching and example, that, though they may be inferior in numbers, they are not surpassed in zeal for study by the highest churches of England.

"[42] Eadmer complained about this prejudice, stating that English nationality debarred a man from achieving high office in the church, however worthy he was.

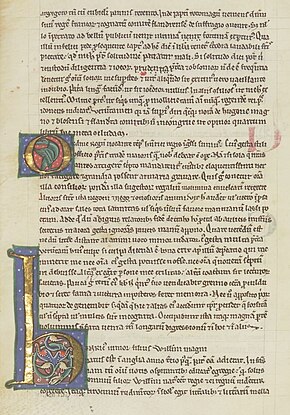

[43] Manuscript production in most of England declined sharply immediately after the Conquest and revived at the end of the century, but Worcester was an exception to this pattern.

[47] Southern suggests that the works "may possibly be connected with the election of Nicholas as prior in 1113",[45] and the scholars Andrew Turner and Bernard Muir state that the Vita and Miracula must have been completed before 1116.

[49] The historian William Smoot argues that Eadmer was chosen in order to enhance Worcester's spiritual prestige by associating it with that of Canterbury.

The hagiographer Osbern had written that Edgar fathered his eldest son, Edward the Martyr, by seducing a nun, and Eadmer was anxious to disprove the allegation.

It is thought likely that there was an earlier unrecorded coronation,[54] but Nicholas wrote that Edgar delayed out of "piety ... until he might be capable of controlling and overcoming the lustful urges of youth".

But he felt so guilty about his transgression that when he went to sleep he was plagued by repeated nightmares, and finally realised that the only way to stop them was to confess to Wulfstan and ask for pardon, which he did and was granted forgiveness.

The historian Martin Brett comments that Nicholas gave him "excellent advice on his future conduct", and that this letter and the one on Edward the Martyr "display a wide historical learning".

[62] Wormald comments: Benedictine monks became dominant in the English church in the reign of King Edgar, but in the eleventh century an increasing number of bishops were secular clergy, especially royal clerks.

[64] All Archbishops of Canterbury were monks (apart from Stigand) from Edgar's reign until the death of Ralph in 1122, but by this time almost all bishops were secular clergy, and most were former clerks of the royal chapel.

[42] Nicholas's death in June 1124 left the proponents of a free election leaderless, and the monks had to accept Queen Adeliza's chancellor, Simon, who was ordained a priest on 17 May 1125 and consecrated as Bishop of Worcester the next day.

But Rome was increasingly opposing lay control over episcopal appointments, and Pope Callixtus II had come close to quashing the election of William de Corbeil partly on the ground that the Canterbury electors had been unwilling to accept him.