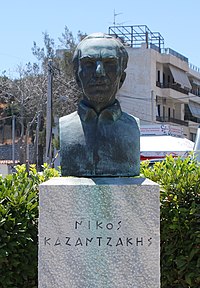

Nikos Kazantzakis

He also translated a number of notable works into Modern Greek, such as the Divine Comedy, Thus Spoke Zarathustra, On the Origin of Species, and Homer's Iliad and Odyssey.

Together they travelled for two years through places where Greek Orthodox Christian culture flourished, largely due to the enthusiastic nationalism of Sikelianos.

Between 1922 and his death in 1957, he sojourned in Paris and Berlin (from 1922 to 1924), Italy, Russia (in 1925), Spain (in 1932), and then later in Cyprus, Aegina, Egypt, Mount Sinai, Czechoslovakia, Nice (he later bought a villa in nearby Antibes, in the Old Town section near the famed seawall), China, and Japan.

He never became a committed communist but visited the Soviet Union and stayed with the Left Opposition politician and writer Victor Serge.

As a journalist, in 1926 he interviewed prime minister of Spain Miguel Primo de Rivera and the Italian dictator Benito Mussolini.

Kazantzakis developed this famously pithy phrasing of the philosophical ideal of cynicism, which dates back to at least the second century CE.

[20] Kazantzakis's first published work was the 1906 narrative, Serpent and Lily (Όφις και Κρίνο), which he signed with the pen name Karma Nirvami.

In 1907 Kazantzakis went to Paris for his graduate studies and was deeply influenced by the philosophy of Henri Bergson, primarily the idea that a true understanding of the world comes from the combination of intuition, personal experience, and rational thought.

Later, in 1909, he wrote a one-act play titled Comedy, which was filled with existential themes, predating the post-World War II existentialist movement in Europe spearheaded by writers like Jean-Paul Sartre and Camus.

After completing his studies in Paris, he wrote the tragedy, "The Master Builder" (Ο Πρωτομάστορας), based on a popular Greek folkloric myth.

Countries he visited include: Germany, Italy, France, The Netherlands, Romania, Egypt, Russia, Japan, and China, among others.

[21] These works also explore what Kazantzakis believed to be the unique physical and spiritual location of Greece, a nation that belongs to neither the East nor the West, an idea he put forth in many of his letters to friends.

The use of Demotic, among writers, gradually started to gain the upper hand only at the turn of the 20th century, under the influence of the New Athenian School (or Palamian).

Several critics have argued that Kazantzakis's writing was too flowery, filled with obscure metaphors, and difficult to read despite being written in Demotic Greek.

[21] Throughout his life, Kazantzakis reiterated his belief that "only socialism as the goal and democracy as the means" could provide an equitable solution to the "frightfully urgent problems of the age in which we are living.

"[24] Following the war, he was temporarily leader of a minor Greek leftist party, while in 1945 he was, among others, a founding member of the Greek-Soviet friendship union.

As a young man he took a month long trip to Mount Athos, a monastic retreat and major spiritual center for Greek Orthodoxy.

[26] Scholars theorize that Kazantzakis's difficult relationship with many members of the clergy and with more religiously conservative literary critics, came from his questioning.

His reply was: "You gave me a curse, Holy fathers, I give you a blessing: may your conscience be as clear as mine and may you be as moral and religious as I" ("Μου δώσατε μια κατάρα, Άγιοι πατέρες, σας δίνω κι εγώ μια ευχή: Σας εύχομαι να 'ναι η συνείδηση σας τόσο καθαρή, όσο είναι η δική μου και να 'στε τόσο ηθικοί και θρήσκοι όσο είμαι εγώ").

While the excommunication was rejected by the top leadership of the Orthodox Church, it became emblematic of the persistent disapprobation from many Christian authorities for his political and religious views.

[30] These scholars argue that, if anything, Kazantzakis was acting in accordance to a long tradition of Christians who publicly struggled with their faith, and grew a stronger and more personal connection to God through their doubt.