Nine-banded armadillo

The nine-banded armadillo is a solitary, mainly nocturnal[4][5] animal, found in many kinds of habitats, from mature and secondary rainforests to grassland and dry scrub.

[8][9] The outer shell is composed of ossified dermal scutes covered by nonoverlapping, keratinized epidermal scales, which are connected by flexible bands of skin.

The second is possible due to its ability to hold its breath for up to six minutes, an adaptation originally developed for allowing the animal to keep its snout submerged in soil for extended periods while foraging.

It cannot thrive in particularly cold or dry environments, as its large surface area, which is not well insulated by fat, makes it especially susceptible to heat and water loss.

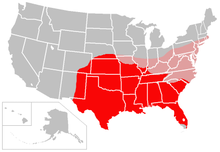

By 1995, the species had become well established in Texas, Oklahoma, Louisiana, Arkansas, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia and Florida, and had been sighted as far afield as Kansas, Missouri, Tennessee, Kentucky, and Carolinas.

[12] The primary cause of this rapid expansion is explained simply by the species having few natural predators within the United States, little desire on the part of Americans to hunt or eat the armadillo, and the animals' high reproductive rate.

The northern expansion of the armadillo is expected to continue until the species reaches as far north as Ohio, Pennsylvania, New Jersey and Connecticut, and all points southward on the East Coast of the United States.

Further northward and westward expansion will probably be limited by the armadillo's poor tolerance of harsh winters, due to its lack of insulating fat and its inability to hibernate.

[12] As of 2009, newspaper reports indicated the nine-banded armadillo seems to have expanded its range northward as far as Omaha, Nebraska in the west, and Kentucky Dam and Evansville, Indiana, in the east.

[10] In late 2009, North Carolina began considering the establishment of a hunting season for armadillo, following reports that the species has been moving into the southern reaches of the state (roughly between the areas of Charlotte and Wilmington).

They forage for meals by thrusting their snouts into loose soil and leaf litter and frantically digging in erratic patterns, stopping occasionally to dig up grubs, beetles (perhaps the main portion of this species' prey selection), ants, termites, grasshoppers, other insects, millipedes, centipedes, arachnids, worms, and other terrestrial invertebrates, which their sensitive noses can detect through 8 in (20 cm) of soil.

They supplement their diets with amphibians and small reptiles, especially in more wintery months when such prey tends to be more sluggish, and occasionally bird eggs and baby mammals.

Occasionally, a large predator may be able to ambush the armadillo before it can clear a distance, and breach the hard carapace with a well-placed bite or swipe.

Predators are rarely able to dislodge the animal once it has burrowed itself, and abandon their prey when they cannot breach the armadillo's armor or grasp its tapered tail.

[10] Due to their softer carapaces, juvenile armadillos are more likely to fall victim to natural predation and their cautious behavior generally reflects this.

Young nine-banded armadillos tend to forage earlier in the day and are more wary of the approach of an unknown animal (including humans) than are adults.

[29] They are typically hunted for their meat, which is said to taste like pork, but are more frequently killed as a result of their tendency to steal the eggs of poultry and game birds.