Nine Years' War

The Truce of Ratisbon guaranteed these new borders for twenty years, but concerns among European Protestant states over French expansion and anti-Protestant policies led to the creation of the Grand Alliance, headed by William of Orange.

Louis XIV also recognised William III as the rightful king of England, while the Dutch acquired barrier fortresses in the Spanish Netherlands to help secure their borders and were granted a favorable commercial treaty.

However, both sides viewed the peace as only a pause in hostilities, since it failed to resolve who would succeed the ailing and childless Charles II of Spain as ruler of the Spanish Empire, a question that had dominated European politics for over 30 years.

With Leopold I unwilling to fight on two fronts, a strong neutralist party in the Dutch Republic tying William's hands and the Elector of Brandenburg stubbornly holding to his alliance with Louis, no possible outcome could occur but complete French victory.

However, Louis had sound reasons to feel satisfied since the Emperor and German princes were fully occupied in Hungary, and in the Dutch Republic, William of Orange remained isolated and powerless, largely because of the pro-French mood in Amsterdam.

[34] Louis's seemingly endless territorial claims, coupled with his persecution of Protestants, enabled William of Orange and his party to gain the ascendancy in the Dutch Republic and finally lay the groundwork for his long-sought alliance against France.

[40] Thus, Frederick-William, spurning his French subsidies, ended his alliance with France and reached agreements with William of Orange, the Emperor and King Charles XI of Sweden, the last of which by temporarily putting aside their differences over Pomerania.

Habsburg victories along the Danube at Buda in September 1686,[44] and Mohács a year later[45] had convinced the French that the Emperor, in alliance with Spain and William of Orange, would soon turn his attention towards France and retake what had recently been won by Louis's military intimidation.

The day after Louis issued his manifesto – well before his enemies could have known its details – the main French army crossed the Rhine as a prelude to investing Philippsburg, the key post between Luxembourg (annexed in 1684) and Strasbourg (seized in 1681), and other Rhineland towns.

In the east, an Imperial army, now manned with veteran officers and men, had dispelled the Turkish threat and crushed Imre Thököly's revolt in Hungary; while in the west and north, William of Orange was fast becoming the leader of a coalition of Protestant states, anxious to join with the Emperor and Spain, and end the hegemony of France.

His open Catholicism and his dealings with Catholic France had also strained relations between England and the Dutch Republic, but because his daughter Mary was the Protestant heir to the English throne, her husband William of Orange had been reluctant to act against James II for fear it would ruin her succession prospects.

His experience and knowledge of European affairs made him the indispensable director of Allied diplomatic and military strategy, and he derived additional authority from his enhanced status as king of England – even the Emperor Leopold ... recognized his leadership.

At the same time, William III assumed command of government troops in Ireland and gained an important success at The Battle of the Boyne in July 1690, before victory at Beachy Head gave the French temporary control of the English Channel.

Despite receiving reinforcements and a new general in the Marquis de St Ruth, the Franco-Irish army was defeated at Aughrim on 12 July 1691; the war in Ireland ended with the Treaty of Limerick in October, allowing the bulk of the Williamite forces to be shipped to the Low Countries.

On 12 May 1689 the Dutch and the Holy Roman Emperor had signed an offensive compact in Vienna, the aims of which were no less than to force France back to her borders as they were at the end of the Franco-Spanish War (1659), thus depriving Louis XIV of all his gains since his personal rule began.

Like the Dutch the English were not preoccupied with territorial gains on the Continent, but were deeply concerned with limiting the power of France to defend against a Jacobite restoration (Louis XIV threatened to overthrow the Glorious Revolution and the precarious political settlement by supporting the old king over the new one).

On 1 July Luxembourg secured a clear tactical victory over Waldeck at the Battle of Fleurus; but his success produced little benefit – Louis XIV's concerns for the dauphin on the Rhine (where Marshal de Lorge now held actual command) overrode strategic necessity in the other theatres and forestalled a plan to besiege Namur or Charleroi.

Talks were hampered, however, by Louis' reluctance to cede his earlier gains (at least those made in the Reunions) and, in his deference to the principle of the divine right of kings, his unwillingness to recognise William III's claim to the English throne.

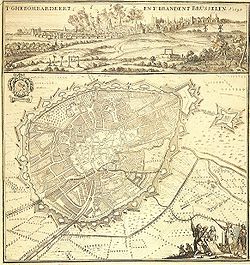

[101] Over the winter of 1691/92 the French devised a grand plan to gain the ascendancy over their enemies – a design for the invasion of England in one more effort to support James II in his attempts to regain his kingdoms; and a simultaneous assault on Namur in the Spanish Netherlands.

Yet the battle itself was not the death-blow for the French navy: the subsequent mismanagement and underfunding of the fleet under Pontchartrain, coupled with Louis' own personal lack of interest, were central to France's loss of naval superiority over the English and Dutch during the Nine Years' War.

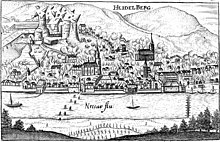

[115] French arms at Heidelberg, Rosas, Huy, Landen, Charleroi and Marsaglia had achieved considerable battlefield success, but with the severe hardships of 1693 continuing through to the summer of 1694 France was unable to expend the same level of energy and finance for the forthcoming campaign.

[116] In the background, Louis XIV's agents were working hard diplomatically to unhinge the coalition but the Emperor, who had secured with the Allies his 'rights' to the Spanish succession should Charles II die during the conflict, did not desire a peace that would not prove personally advantageous.

[119] Elsewhere, de Lorge marched and manoeuvred against Baden on the Rhine with undramatic results before the campaign petered out in October; while in Italy, the continuing problems with French finance and a complete breakdown in the supply chain prevented Catinat's push into Piedmont.

[121] In 1695 French arms suffered two major setbacks: first was the death on 5 January of Louis XIV's greatest general of the period, Marshal Luxembourg (to be succeeded by the Duke of Villeroi); the second was the loss of Namur, which was considered to be the strongest fortress in Europe.

In May 1696, Jean Bart slipped the blockade of Dunkirk and struck a Dutch convoy in the North Sea, burning 45 of its ships; on 18 June 1696 he won the battle at Dogger Bank; and in May 1697, the Baron of Pointis with another privateer squadron attacked and seized Cartagena, earning him, and the king, a share of 10 million livres.

In Spain, in the Rhineland, and in the Low Countries, Louis XIV's forces only barely held their own: the bombardment of the French channel ports, the threats of invasion, and the loss of Namur were causes of great anxiety for the King at Versailles.

Despite numerical superiority, the English colonists suffered repeated defeats as New France effectively organised its French regulars, local militiamen and Indian allies (notably the Algonquins and Abenakis), to attack frontier settlements.

[139] The war dragged on for several years longer in a series of desultory sallies and frontier raids: neither the leaders in England nor France thought of weakening their position in Europe for the sake of a knock-out blow in North America.

William III had no intention of continuing the war or pressing for Leopold I's claims in the Rhineland or for the Spanish succession: it seemed more important for Dutch and British security to obtain Louis XIV's recognition of the 1688 revolution.

Additionally, Prince Eugene of Savoy's decisive victory over the Ottoman Turks at the Battle of Zenta – leading to the Treaty of Karlowitz in 1699 – consolidated the Austrian Habsburgs and tipped the European balance of power in favour of the Emperor.