Nineteenth-century theatrical scenery

Part of a broader artistic movement, it included a focus on everyday middle-class drama, ordinary speech, and simple settings.

Theatrical designers and directors began meticulously researching historical accuracy for their productions, which meant that scenery could no longer be drawn from stock - which was typically used over and over again in generic settings for different shows.

[3] Madame Vestris had introduced realistic stage furnishing in 1836 at her little Olympic Theatre in London, and forced them on American managers when she toured that country in 1838-1839.

A box set consists of flats hinged together to represent a room; it often has practicable elements, such as doors and windows, which can be used during the course of a play or show.

[5] With the new pursuit of realism, room-like box settings now had heavy molding, real doors with doorknobs, and ample accurate furniture.

Having the box set also meant that many theater artists began to stage all the action behind the proscenium in the late 1800s, thus reinforcing the illusion of a fourth wall.

Scenic artists from Europe brought with them the Romantic, Baroque, or classical landscapes that they knew from their homes, but the styles seemed to change when they landed on the American shore.

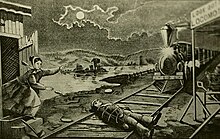

Many historians believe that the popularity of melodrama, with its emphasis on stage spectacle and special effects, accelerated these technological innovations: For example, Dion Boucicault was responsible for the introduction of fireproofing in the theater when one of his melodramatic plays called for an onstage fire.

This soon gave way to the moving panorama: a setting painted on a long cloth, which could be unrolled across the stage by turning spools, created an illusion of movement and changing locales.

[10] The advent of the panoramas coupled with Charles Kean’s invention of the Corsican trap meant that entire horse and chariot races could be enacted on stage.

On February 7, 1880, the Spirit of the Times announced: "Tonight Mr. J. Steele MacKaye will open the most exquisite theatre in the world, and all New York will assemble to do honor to the realization of his artistic visions…Mr.

MacKaye will play the drama Hazel Kirke through with only two-minute waits between the acts, and will then exhibit the double stage—one compartment set for the kitchen of Blackburn Mill and other as boudoir at Fairy Grove Villa."

"[It consists] of two theatrical stages, one above another, to be moved up and down as an elevator car is operated in a high building, and so that either one of them can easily and quickly be at any time brought to the proper level for acting thereon in front of the auditorium.

Though scenic painters had to learn to subdue their colors to the increased candle-power, the brightness only further highlighted the disparity between three-dimensional set pieces and their two-dimensional backdrop and led to the latter's eventual decline.

Adolphe Appia and Edward Gordon Craig would be the ones to revolt against the idea of the actor standing on a flat floor surrounded by “realistic” painted canvases.

The 20th century would bring the scenic designer an entirely new aesthetic for the world of the theatre in the form of Henrik Ibsen and Modernism.