Non-Euclidean geometry

The debate that eventually led to the discovery of the non-Euclidean geometries began almost as soon as Euclid wrote Elements.

In the Elements, Euclid begins with a limited number of assumptions (23 definitions, five common notions, and five postulates) and seeks to prove all the other results (propositions) in the work.

These theorems along with their alternative postulates, such as Playfair's axiom, played an important role in the later development of non-Euclidean geometry.

These early attempts at challenging the fifth postulate had a considerable influence on its development among later European geometers, including Witelo, Levi ben Gerson, Alfonso, John Wallis and Saccheri.

He finally reached a point where he believed that his results demonstrated the impossibility of hyperbolic geometry.

In 1766 Johann Lambert wrote, but did not publish, Theorie der Parallellinien in which he attempted, as Saccheri did, to prove the fifth postulate.

[8] The beginning of the 19th century would finally witness decisive steps in the creation of non-Euclidean geometry.

Circa 1813, Carl Friedrich Gauss and independently around 1818, the German professor of law Ferdinand Karl Schweikart[9] had the germinal ideas of non-Euclidean geometry worked out, but neither published any results.

[14] Arthur Cayley noted that distance between points inside a conic could be defined in terms of logarithm and the projective cross-ratio function.

The method has become called the Cayley–Klein metric because Felix Klein exploited it to describe the non-Euclidean geometries in articles[15] in 1871 and 1873 and later in book form.

As the first 28 propositions of Euclid (in The Elements) do not require the use of the parallel postulate or anything equivalent to it, they are all true statements in absolute geometry.

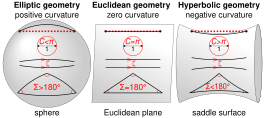

The simplest model for elliptic geometry is a sphere, where lines are "great circles" (such as the equator or the meridians on a globe), and points opposite each other are identified (considered to be the same).

This introduces a perceptual distortion wherein the straight lines of the non-Euclidean geometry are represented by Euclidean curves that visually bend.

Furthermore, since the substance of the subject in synthetic geometry was a chief exhibit of rationality, the Euclidean point of view represented absolute authority.

The philosopher Immanuel Kant's treatment of human knowledge had a special role for geometry.

[23] Non-Euclidean geometry is an example of a scientific revolution in the history of science, in which mathematicians and scientists changed the way they viewed their subjects.

[24] Some geometers called Lobachevsky the "Copernicus of Geometry" due to the revolutionary character of his work.

This curriculum issue was hotly debated at the time and was even the subject of a book, Euclid and his Modern Rivals, written by Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (1832–1898) better known as Lewis Carroll, the author of Alice in Wonderland.

In analytic geometry a plane is described with Cartesian coordinates: The points are sometimes identified with generalized complex numbers z = x + y ε where ε2 ∈ { –1, 0, 1}.

[29] Hyperbolic geometry found an application in kinematics with the physical cosmology introduced by Hermann Minkowski in 1908.

He realized that the submanifold, of events one moment of proper time into the future, could be considered a hyperbolic space of three dimensions.

For instance, the split-complex number z = eaj can represent a spacetime event one moment into the future of a frame of reference of rapidity a.

[32] Another view of special relativity as a non-Euclidean geometry was advanced by E. B. Wilson and Gilbert Lewis in Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1912.

"Three scientists, Ibn al-Haytham, Khayyam, and al-Tusi, had made the most considerable contribution to this branch of geometry, whose importance was completely recognized only in the nineteenth century.

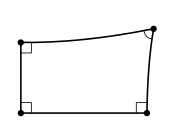

In essence, their propositions concerning the properties of quadrangle—which they considered assuming that some of the angles of these figures were acute of obtuse—embodied the first few theorems of the hyperbolic and the elliptic geometries.

By their works on the theory of parallel lines Arab mathematicians directly influenced the relevant investigations of their European counterparts.

The first European attempt to prove the postulate on parallel lines – made by Witelo, the Polish scientists of the thirteenth century, while revising Ibn al-Haytham's Book of Optics (Kitab al-Manazir) – was undoubtedly prompted by Arabic sources.

The proofs put forward in the fourteenth century by the Jewish scholar Levi ben Gerson, who lived in southern France, and by the above-mentioned Alfonso from Spain directly border on Ibn al-Haytham's demonstration.

Above, we have demonstrated that Pseudo-Tusi's Exposition of Euclid had stimulated both J. Wallis's and G. Saccheri's studies of the theory of parallel lines.

""But in a manuscript probably written by his son Sadr al-Din in 1298, based on Nasir al-Din's later thoughts on the subject, there is a new argument based on another hypothesis, also equivalent to Euclid's, [...] The importance of this latter work is that it was published in Rome in 1594 and was studied by European geometers.