Norman Selfe

Norman Selfe (9 December 1839 – 15 October 1911) was an Australian engineer, naval architect, inventor, urban planner and outspoken advocate of technical education.

[3] Selfe's cousin Edward Muggeridge grew up in the same town but moved to the United States in 1855, restyled himself Eadweard Muybridge, and achieved global fame as a pioneer in the new field of photography.

[4] It so happened that at the time of my visit to that cottage at the Quay that [Maybanke's] two clever brothers, Norman and Harry, had just completed the first "bike" ever made in Australia, known as a velocipede in those days, and these two young engineers were proudly just going "down the street" on their foot-worked machine, with the knowledge they were the first here to travel in such a contraption ...

[1] One of the reasons they emigrated to the colony of New South Wales was to enable him and his brother Harry to undertake engineering apprenticeships without having to pay the heavy premium required by large firms in London.

[6] They initially resided in the nearby Rocks district in a small house that had previously been the first Sydney home of Mary Reibey, a former convict who became Australia's first businesswoman.

[5] Selfe very quickly began his career as an engineer, taking articles of apprenticeship to the ironmaster Peter Nicol Russell, at whose firm he worked in several departments and eventually became its chief draughtsman.

[8] In 1859, when PN Russell & Co expanded to a site in Barker Street near the head of Darling Harbour, Selfe drew up plans for the new works and the wharf, and oversaw their construction.

In an address to the Engineering Section of the Royal Society of New South Wales in 1900, Selfe recalled his work for Russell's: While there [I] prepared plans for numbers of flour mills, and for the first ice-making machines, designing machinery for the multifarious requirements of colonial industries, many of which (such as sheep-washing and boiling down) no longer exist on the old lines.

[9]While at Russell's, Selfe made several innovations in the design and construction of dredges for "deeping our harbours and rivers" – something of crucial importance to industry in early Sydney.

[1][14] In this role he oversaw the design and construction of the mail ship SS Governor Blackall, personally commissioned for the Queensland government by the Premier Charles Lilley in 1869.

[15] The Sydney-built but Queensland-owned ship was an attempt to break what was later described as the "capricious monopoly" of the Australasian Steam Navigation Company on coastal trade and mail delivery from England.

Upon his return from an overseas trip through America, Britain and continental Europe in 1884–85, where he visited engineering works and technical education facilities in search of new ideas to take back to Sydney, Selfe set up a new office in Lloyd's Chambers at 348 George Street.

He also designed the first ice-making machines in New South Wales, introduced the first lifts, patented an improved system of baling wool which increased capacity fourfold, and oversaw hydraulic and electric light installations in the city and the carriages on its railway network.

When that day arrives, we shall look back with curiosity and wonder at the continued blindness and negligence from which our city – so highly gifted by nature – had suffered so long.

[27] In 1887 Selfe published proposals for a city underground railway, with stations at Wynyard, the Rocks and Circular Quay, and a loop to Woolloomooloo and the eastern suburbs.

He presented these schemes to the Royal Commission on City and Suburban Railways in 1890; but nothing was to come of it, largely because the 1890s depression brought public works initiatives to a standstill.

He advocated a more utilitarian and less literary education system, to produce a skilled workforce that could realise Australia's potential as an efficient industrial state.

[47] Due to the colony's rapidly expanding population and demand for skilled labour, there were increasing calls in the 1870s for a formal system of technical education.

[49] In 1878, the association joined forces with the New South Wales Trades and Labour Council and the Sydney Mechanics' School of Arts to form the Technical and Working Men's College.

He rejected the non-technical, non-practical approach of the school's model and campaigned instead for the establishment of a proper institute of technical education, where instructors would be skilled tradesmen with practical industrial experience.

During this time the relationship between the board and the government deteriorated with Selfe being overtly critical of two powerful institutions: the newly formed Department of Public Instruction and the University of Sydney.

[61] In an address at the annual presentation of prizes at Sydney Technical College in 1887, Selfe alienated the Minister of Public Instruction and others by being openly contemptuous of the traditional pursuits of schools and universities: [T]he whole experience of the past goes to show that the learning of the schools has had little, if anything, to do with the material advancement of the world, and that while it may have produced intellectual giants, subjective teaching has not brought forth those men who have been inventors and manufacturers that have entirely changed the character of our civilisation.

In his 1888 address to Sydney Technical College students on prize night, he again caused affront to the establishment when he called for greater diversity of educational opportunities in the colony: [I]t is not ... easy ... to see why the general public should pay so many thousands a year to make our future professional men in medicine and law in the colony, to form part of the so-called upper classes, when our "principles" will not allow us to pay just a little more in order to have, say, our locomotives made here, and when we are doing so very little, proportionately, to train and educate the artisans who make these locomotives, and who belong to a much less wealthy and influential level in society.

However, Mandelson sounds a critical note: Selfe's contempt for the liberal arts tradition and the priority he accorded practical skill have certain implications which cannot be commended.

Selfe bought waterfront land and built twin terraced houses called Normanton and Maybank, which are still at 21 and 23 Wharf Road, Birchgrove.

Described at the time as having "more novelties both externally and internally than any other house in the colony"[74] including terracotta lyrebird reliefs by artist Lucien Henry on the front wall, and a tower purpose-built for Selfe to pursue his hobby of astronomy.

[78] Around 1894, the family moved, this time to Hornsby Shire, where a new Selfe-designed house, Gilligaloola, was built on 11 acres (4.5 ha) purchased by Selfe ten years earlier.

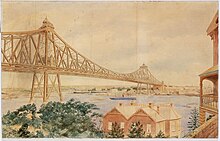

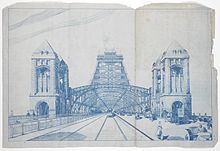

His obituary in the journal Building concluded: ... [T]here is none today who can replace the noble personality, that keen energetic brain ever ready to give of its wonderful store of knowledge, and that happy spirit ever bright, ever optimistic, even though crushed beneath the cruel and unjust blow of the non-acceptance of his prize design for the North Shore bridge.

We will always remember the bright gleam in his eyes as they peered beyond the anxiety of today, looked afar to the future glory of his beloved Sydney where in his dreams he saw his mighty bridge spanning what he called "God's noblest waterway".

[13] Twenty-one years later, on 11 March 1932 Marion's charred body was found in her new house, also in Normanhurst where she lived alone, having reportedly set fire to her clothes when lighting a candle.