Normandie-class battleship

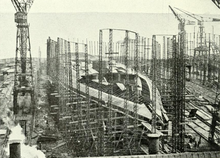

The ships were never completed due to shifting production requirements and a shortage of labor after the beginning of World War I in 1914.

The first four ships were sufficiently advanced in construction to permit their launching to clear the slipways for other, more important work.

The last ship, Béarn, which was not significantly advanced at the time work halted, was converted into an aircraft carrier in the 1920s.

In December 1911, the French Navy's Technical Committee (Comité technique) issued a report that examined the design of the Bretagne class that had been ordered for 1912.

One used two sets of direct-drive steam turbines, as in the Bretagne class; the one ultimately selected was a hybrid system that used one set of direct-drive turbines on the two inner propeller shafts, and two vertical triple-expansion steam engines (VTE) on the outer shafts for low-speed cruising.

The fifth ship, Béarn, was instead equipped with two sets of turbines to allow her to match the fuel consumption rate of the turbine-equipped Bretagne class.

[2] The General Staff decided in March 1912 to retain the 340 mm gun of the Bretagne class and favored the all-turbine design.

[3] The following month, the Naval Supreme Council (Conseil supérieur de la Marine) could not reach a decision on the quadruple turret as it was still being developed, but wished to revisit the issue once it was further along.

[4] It accepted the hybrid propulsion system, and the armor layout of the Bretagne class was to be retained, with an increase in the thickness of the main belt if possible.

[7] The first four ships were equipped with one set of steam turbines driving the inner pair of four-bladed, 5.2 m (17 ft 1 in) propellers.

The last ship, Béarn, was equipped with two sets of Parsons turbines, each driving a pair of three-bladed, 3.34 m propellers.

[8] The ships' engines were rated at 32,000 metric horsepower (23,536 kW; 31,562 shp) and were designed to give them a speed of 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph), although use of forced draft was intended to increase their output to 45,000 PS (33,097 kW; 44,384 shp) and the maximum speed to 22.5 knots (41.7 km/h; 25.9 mph).

[11] The main battery of the Normandie class consisted of a dozen 45-caliber Canon de 340 mm Modèle 1912M guns mounted in three quadruple turrets.

[16] The ships would also have been armed with a secondary battery of twenty-four 55-caliber 138.6 mm Modèle 1910 guns, each singly mounted in casemates near the main-gun turrets.

[20] Above the waterline belt was an upper strake of 160-millimeter armor that extended between the fore and aft groups of casemates for the secondary armament.

The portions of the barbettes that extended outside the upper armor were protected by 250-millimeter (9.8 in) plates, while the interior surfaces were only 50 millimeters (2 in) thick to save weight.

The lower armored deck consisted of a single 14-millimeter (0.6 in) plate of mild steel for a width of 7 meters (23 ft) along the centerline, and another layer of the same thickness was added outboard of that.

Their propulsion machinery spaces and magazines were protected by a torpedo bulkhead that consisted of two 10-millimeter (0.4 in) layers of nickel-chrome steel plates.

The outer side of the bulkhead was lined with a 10-millimeter plate of corrugated flexible steel intended to absorb the force of a torpedo detonation.

Béarn had been planned to be ordered on 1 October 1914, but it was brought forward to 1 January; the five ships would permit the creation of two four-ship divisions with the three Bretagne-class dreadnoughts then under construction.

The mobilization in July greatly impeded construction as workmen who were in the reserves were called up for military service, and work was effectively halted later that month.

In light of such constraints, the navy decided that only those ships that could be completed quickly, such as the Brétagnes, would be worked upon, although sufficient construction of the first four Normandies was authorized to clear the slipways for other purposes.

The General Staff replied that the ships would need a top speed of 26 to 28 kn (48 to 52 km/h; 30 to 32 mph) and a more powerful main battery.

[31] The need to engage targets at longer ranges was confirmed by the examination of one of the ex-Austrian Tegetthoff-class ships that had been surrendered to France at the end of the war.

[35] The ships were formally cancelled in the 1922 construction program, and were laid up in Landevennec and cannibalized for parts before being broken up in 1923–1926.

Transverse arresting wires that were weighted by sandbags were improvised, and the evaluation successfully took place off Toulon in late 1920.

Conversion work began in August 1923, and was completed by May 1927 using the hybrid propulsion system from Normandie with a dozen Normand boilers.