Viking activity in the British Isles

[4][b] At the start of the early medieval period, Scandinavian kingdoms had developed trade links reaching as far as southern Europe and the Mediterranean, giving them access to foreign imports, such as silver, gold, bronze, and spices.

In Cornwall, Cumbria, Wales, and south-west Scotland, the Celtic Brythonic languages were spoken (their modern descendants include Welsh and Cornish).

The Picts, who spoke the Pictish language, lived in the area north of the Forth and Clyde rivers, which now constitutes a large portion of modern-day Scotland.

In northern Britain, in the area roughly corresponding to modern-day Scotland, lived three distinct ethnic groups in their own respective kingdoms: the Picts, Scots, and Britons.

[8] The Scots, according to written sources, constituted a tribal group which had crossed to Britain from Dalriada in the north of Ireland during the late-fifth century.

[10] By the mid-ninth century, Anglo-Saxon England comprised four separate and independent kingdoms: East Anglia, Wessex, Northumbria, and Mercia, the last of which was the strongest military power.

[11] The majority of the populace lived in the countryside, although a few large towns had developed, notably London and York, which became centres of royal and ecclesiastical administration.

Here, these monasteries had often been positioned on small islands and in other remote coastal areas so that the monks could live in seclusion, devoting themselves to worship without the interference of other elements of society.

The first known account of a Viking raid in Anglo-Saxon England comes from 789, when three ships from Hordaland (in modern Norway) landed in the Isle of Portland on the southern coast of Wessex.

In a document dating to 792, King Offa of Mercia set out privileges granted to monasteries and churches in Kent, but he excluded military service "against seaborne pirates with migrating fleets", showing that Viking raids were already an established problem.

In a letter of 790–92 to King Æthelred I of Northumbria, Alcuin berated English people for copying the fashions of pagans who menaced them with terror.

[14] The next recorded attack against the Anglo-Saxons came the following year, in 793, when the monastery at Lindisfarne, an island off England's eastern coast, was sacked by a Viking raiding party on 8 June.

[citation needed] The Anglo-Saxon rulers paid large sums, Danegelds, to Vikings, who mostly came from Denmark and Sweden who arrived to the English shores during the 990s and the first decades of the 11th century.

[27] People taken captive during the viking raids in Western Europe could be sold to Moorish Spain via the Dublin slave trade[28] or transported to Hedeby or Brännö and from there via the Volga trade route to Russia, where slaves and furs were sold to Muslim merchants in exchange for Arab silver dirham and silk, which have been found in Birka, Wollin and Dublin.

[32] The slave trade between the Vikings and the Muslims in Central Asia is known to have functioned from at least between 786 and 1009, as large quantities of silver coins from the Samanid Empire have been found in Scandinavia from these years.

[13] The coins themselves came from a wide range of different kingdoms, with Wessex, Mercian, and East Anglian examples found alongside foreign imports from Carolingian-dynasty Francia and from the Arab world.

[35] Counterattacks concluded in a decisive defeat for Anglo-Saxon forces at York on 21 March 867, and the deaths of Northumbrian leaders Ælla and Osberht.

The treaty is one of the few existing documents[c] of Alfred's reign and survives in Old English in Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, Manuscript 383, and in a Latin compilation, known as Quadripartitus.

[35][42] Alfred's policy of opposing the Viking settlers continued under his daughter Æthelflæd, who married Æthelred, Ealdorman of Mercia, and also under her brother, King Edward the Elder (reigned 899–924).

Æthelstan defeated them at the Battle of Brunanburh, a victory which gave him great prestige both in the British Isles and on the Continent and led to the collapse of Viking power in northern Britain.

[46] However, in the reigns of his son Edward the Martyr, who was murdered in 978, and then Æthelred the Unready, the political strength of the English monarchy waned, and, in 980, raiders from Scandinavia resumed attacks against England.

This fee did not prove to be enough, and, over the next decade, the English kingdom was forced to pay the Viking attackers increasingly large sums of money.

[46] Many English began to demand that a more hostile approach be taken against the Vikings, and so, on St Brice's Day in 1002, King Æthelred proclaimed that all Danes living in England would be executed.

[47][48] Sweyn continued his raid in England and in 1004 his Viking army looted East Anglia, plundered Thetford and sacked Norwich, before he once again returned to Denmark.

[49] Further raids took place in 1006–1007 then Sweyn was paid over 10 000 pounds of silver to leave, and, in 1009–1012, Thorkell the Tall led a Viking invasion into England.

[50] Harald Hardrada, King of Norway, led an invasion of England in 1066 with 300 longships and 10,000 soldiers, attempting to seize the English throne during the succession dispute following the death of Edward the Confessor.

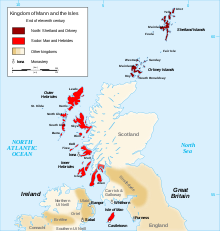

[51] Archaeologists James Graham-Campbell and Colleen E. Batey noted that there was a lack of historical sources discussing the earliest Viking encounters with the British Isles, which would have most probably been amongst the northern island groups, those closest to Scandinavia.