1856 United States presidential election

Pierce had become widely unpopular in the North because of his support for the pro-slavery faction in the ongoing civil war in territorial Kansas, and Buchanan, a former Secretary of State, had avoided the divisive debates over the Kansas–Nebraska Act by being in Europe as the Ambassador to the United Kingdom.

The 1856 Republican National Convention nominated a ticket led by Frémont, an explorer and military officer who had served in the Mexican–American War.

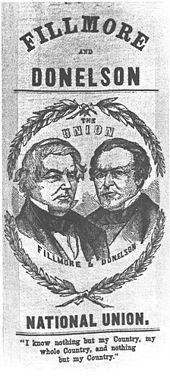

The Know Nothings, who ignored slavery and instead emphasized anti-immigration and anti-Catholic policies, nominated a ticket led by former Whig President Millard Fillmore.

Domestic political turmoil was a major factor in the nominations of both Buchanan and Fillmore, who appealed in part because of their recent time abroad, when they did not have to take a position on the divisive questions related to slavery.

Northern Democrats called for "popular sovereignty", which in theory would allow the residents in a territory to decide for themselves the legal status of slavery.

Buchanan called that position "extremist", warning that a Republican victory would lead to disunion, a then constant issue of political debate which had already been long discussed and advocated.

Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois, who had sponsored the Kansas-Nebraska Act, entered the race in opposition to President Franklin Pierce.

The Seventh Democratic National Convention was held in Smith and Nixon's Hall in Cincinnati, Ohio, on June 2 to 6, 1856.

A host of candidates were nominated for the vice presidency, but a number of them attempted to withdraw themselves from consideration, among them the eventual nominee, John C. Breckinridge of Kentucky.

Breckinridge, besides having been selected as an elector, was also supporting former Speaker of the House Linn Boyd for the vice presidential nomination.

The convention approved an anti-slavery platform that called for congressional sovereignty in the territories, an end to polygamy in Mormon settlements, and federal assistance for a transcontinental railroad—a political outcome of the Pacific Railroad Surveys.

Seward and Chase did not feel that the party was yet sufficiently organized to have a realistic chance of taking the White House and were content to wait until the next election.

McLean's name was initially withdrawn by his manager Rufus Spalding, but the withdrawal was rescinded at the strong behest of the Pennsylvania delegation led by Thaddeus Stevens.

The party gained control over the state governments of California, Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Rhode Island in the 1854 and 1855 elections.

Henry Wilson led northern delegates out of the party's 1855 national council in Philadelphia in protest of it adopting a plank endorsing the Kansas-Nebraska Act.

[6] 70 northern delegates left the 1856 convention to create the North American Party after a resolution calling for the Kansas-Nebraska Act to be repealed was defeated.

Delegates from Ohio, Pennsylvania, Illinois, Iowa, New England, and other northern states bolted when a resolution that would have required all prospective nominees to be in favor of prohibiting slavery north of the 36'30' parallel was voted down.

Although the nativist argument of the American party had considerable success in local and state elections in 1854–55, Fillmore in 1856 concentrated almost entirely on national unity.

The Republican platform opposed the repeal of the Missouri Compromise through the Kansas–Nebraska Act, which enacted the policy of popular sovereignty, allowing settlers to decide whether a new state would enter the Union as free or slave.

In sum, the campaign's true focus was against the system of slavery, which they felt was destroying the republican values that the Union had been founded upon.

The Democrats also supported the plan to annex Cuba, advocated in the Ostend Manifesto, which Buchanan helped devise while serving as minister to Britain.

The most influential aspect of the Democratic campaign was a warning that a Republican victory would lead to the secession of numerous southern states.

Democrats also called on nativists to make common cause with them against the specter of sectionalism even if they had once attacked their political views.

[15] A minor scandal erupted when the Americans, seeking to turn the national dialogue back in the direction of nativism, put out a false rumor that Frémont was in fact a Roman Catholic.

The Democrats ran with it, and the Republicans found themselves unable to counteract the rumor effectively given that while the statements were false, any stern message against those assertions might have crippled their efforts to attain the votes of German Catholics.

Attempts were made to refute it through friends and colleagues, but the issue persisted throughout the campaign and might have cost Frémont the support of a number of American Party members.

After the Supreme Court's controversial Dred Scott v. Sandford ruling in 1857, most of the anti-slavery members of the party joined the Republicans.

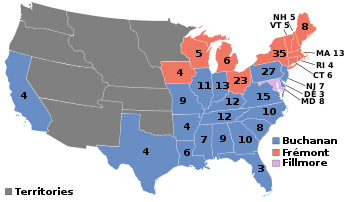

Source: Data from Walter Dean Burnham, Presidential ballots, 1836–1892 (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1955) pp 247–57.

The electors of Wisconsin, delayed by a snowstorm, did not cast their votes for Frémont and Dayton until several days after the appointed time and sent a certificate mentioning this fact.

When the votes for the state were opened by acting Vice President James Mason, he counted them over the objections of the leadership of both Houses of Congress.