North Shore (Lake Superior)

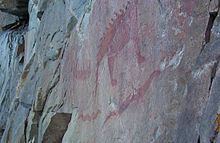

The shore is characterized by alternating rocky cliffs and cobblestone beaches, with forested hills and ridges through which scenic rivers and waterfalls descend as they flow to Lake Superior.

[citation needed] By the 18th century the Ojibwa had settled the length of the North Shore approximately as far as the modern Canadian–Minnesota Border.

The first white explorer to reach Lake Superior was Frenchman Étienne Brûlé who was sent out by Samuel de Champlain to search for the Northwest Passage in 1623 or 1624.

[2] In 1658 two French explorers, Pierre-Esprit Radisson and Médard des Groseilliers, became the first whites to circumnavigate Lake Superior by sailing south along the North Shore.

In the late 1670s, Daniel Greysolon, Sieur du Lhut, helped negotiate a more permanent peace between these tribes, thus providing safe trade across Lake Superior for the French.

In 1688 Jacques de Noyon became the first European to visit the present-day Boundary Waters Canoe Area region west of Lake Superior.

In 1763 according to the terms of the Treaty of Paris, the British took possession of all French holdings east of the Mississippi River, including the North Shore.

Because of this white settlers moved into the region in order to mine the natural resources, thus beginning American settlements on the Minnesotan portion of the North Shore.

Ninety-nine fishermen had settled in northern Minnesota by 1857, when an economic panic caused most of the claims to be abandoned.

In 1875 Philadelphia financier Charlemagne Tower, who owned extensive interests in the Northern Pacific Railroad, began to investigate the possibility of iron mining inland from the North Shore.

(Vast quantities of banded iron formations had been deposited about 2,000 million years ago in the Animikie Group.)

In 1887, when the railroad was completed, the Minnesota Iron Company owned 95.7 miles (154.0 km) of track, 26,800 acres (108 km2) of property, 13 locomotives, 340 cars, the loading docks at Two Harbors and five pit mines.

Although the potential for a lumber industry was recognized early in the course of European settlement, the distances that it would have to be shipped made it uneconomical.

Because of conservation efforts, many of the forests along the North Shore are now protected from deforestation, but there is still a strong paper industry that relies on pulpwood.

The government of Minnesota slowly began to acquire the lands which became the modern North Shore state parks.

Today the North Shore Scenic Drive remains a popular tourist route, starting at the historic Glensheen Mansion, passing several state parks, all the way to Grand Portage.

During recent glaciations, a large amount of the basalt and sandstone, which erode much more easily than granite, was removed by the glaciers.

As the glaciers retreated, they left behind eroded igneous material, much of which covers the rocky beaches on the North Shore.

The melting water from the retreat of the glaciers ran into the basin and began to fill, forming the Great Lakes.

In the south, near Duluth, other materials, such as slate, greywacke and sandstone, are found a short distance inland; but in the north, the entire bedrock made of basalt and gabbro is exposed in patches miles from shore.

The majority of Ontario Provincial Parks are undeveloped nature reserves with no formal campgrounds or visitor centers.