2017 Northern Ireland Assembly election

[3] Theresa Villiers, Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, announced in 2013 that the next Assembly election would be postponed to May 2016, and would be held at fixed intervals of five years thereafter.

Martin McGuinness (Sinn Féin), the deputy First Minister, resigned on 9 January 2017 in protest at the Renewable Heat Incentive scandal (RHI) and other issues, such as the DUP's failure to support funding for inquests into killings during The Troubles and for an Irish language project.

[6] As a result, the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, James Brokenshire, confirmed the same day that a snap election would be held on 2 March.

[7][8][9] McGuinness subsequently announced that, owing to ill-health, he would not be seeking re-election to the Assembly; he then stepped down from leading the Sinn Féin group.

[28] The DUP criticised Nesbitt's position and campaigned arguing that splitting the unionist vote could help Sinn Féin come out as the largest party.

The DUP supported the UK leaving the EU, while nationalist parties and most others opposed, fearing among other things the possibility of a hard border resulting with the Republic of Ireland.

The money came from the Constitutional Research Council, a minor pro-union group chaired by the former vice-chair of the Scottish Conservative Party Richard Cook.

The first column indicates the party of the Member of the House of Commons (MP) returned by the corresponding parliamentary constituency in the general election of 7 May 2015 (under the "first past the post" method).

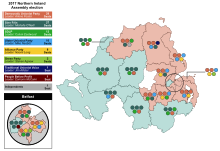

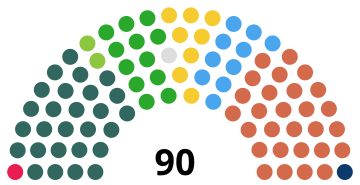

The election marked a significant shift in Northern Ireland's politics, being the first election since Ireland's partition in 1921 in which unionist parties did not win a majority of seats, and the first time that unionist and nationalist parties received equal representation in the Assembly (39 members between Sinn Féin and the SDLP, 39 members between the DUP, UUP, and TUV).

The DUP's loss of seats also prevented it from unilaterally using the petition of concern mechanism, which the party had controversially used to block measures such as the introduction of same-sex marriage to Northern Ireland.

[48] Secretary of State for Northern Ireland James Brokenshire gave the political parties more time to reach a coalition agreement after the 27 March deadline passed.

Various commentators suggested this raised problems for the UK government's role as a neutral arbiter in Northern Ireland, as is required under the Good Friday Agreement.

[58][59][60] Talks between the DUP and Sinn Féin recommenced on 6 February 2018, only days before the mid-February deadline where, in the absence of an agreement, a regional budget would have to be imposed by Westminster.

[61] Despite being attended by Theresa May and Leo Varadkar, the talks collapsed and DUP negotiator Simon Hamilton stated "significant and serious gaps remain between ourselves and Sinn Féin".

[62] The stalemate continued into September, at which point Northern Ireland reached 590 days without a fully functioning administration, eclipsing the record set in Belgium between April 2010 and December 2011.

[67] The Bill became the Northern Ireland (Executive Formation and Exercise of Functions) Act 2018 and came into effect after it received Royal Assent and was passed on 1 November.

[68][69][70] During a question period to the Northern Ireland Secretary on 31 October, Karen Bradley announced that she would hold a meeting in Belfast the following day with the main parties regarding the implementation of the Bill (which was not an Act yet on that day) and next steps towards the restoration of the devolution and that she would fly to Dublin alongside Theresa May's de facto deputy David Lidington to hold an inter-governmental conference with the Irish Government.

Unionist MPs attempted to reconvene the Assembly on 21 October to pass legislation to defeat the measures, but no business could be conducted due to a boycott by Sinn Féin.