Nortraship

The British politician and Nobel Peace Prize laureate of 1959, Philip Noel-Baker commented after the war, "The first great defeat for Hitler was the battle of Britain.

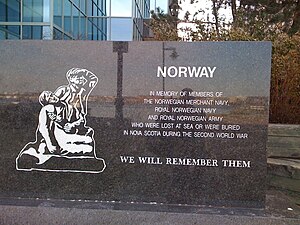

Nortraship was vital to Norway and the exile government as it lacked other means to support the Allied fight against the Axis powers.

In the years after World War I the Norwegian merchant fleet recouped its losses and expanded into new sectors, primarily tankers but also dry cargo vessels.

Called the Scheme Agreement, this stated that a percentage of the Norwegian fleet, including two thirds of the tanker tonnage, was to go on charter to Britain.

These negotiations showed the dual nature of the Norwegian merchant fleet: it was a huge asset and also was vital to both the belligerent factions.

The reasons for Norway being so important for the Allies were the relative decline of the British merchant fleet, overly optimistic prewar tonnage planning and the US Neutrality Act, which effectively forbade US vessels from entering the war zone.

The only other nation with a comparable merchant fleet was Netherlands, but they strongly rejected any tonnage agreement for fear of German reprisals.

The Norwegian ambassador, Erik Colban, and shipowner Ingolf Hysing Olsen were presented with the plan but were leaning towards a joint solution with the British Ministry of Shipping.

The shipping professionals argued that a more independent organisation would be in a better position to safeguard Norwegian interests and the revenue from the fleet.

The Norwegian government now came forward with a cable that stated that the merchant fleet was to be administered jointly from London and New York.

That several of the Nortraship staff had their own shipping interests to take care of further added to the problems of managing the organisation.

On 28 May 1940, Øivind Lorentzen signed a "Memorandum of Understanding" with the British Ministry of Shipping that solved the insurance issue for a period of three months.

Nortraship was the exiled Norwegian government's main source of income and while contributing to the war effort, had to be managed for the highest possible profit.

Nazis and communists tried to demoralise the crews and serious desertion problems were encountered, resulting in ships lying idle for months.

The delegation arrived in New York on 11 June 1940 and started working with the already established committee, the main issues being organisation and the freight earnings from the "free ships" since until then, they had been kept by the shipowners or their US representatives.

It was formulated by Arne Sunde (who later would become Minister of Shipping) on 1 August 1940 and stated that expenses should be paid in sterling currencies, and use of US dollars was to be avoided.

Part of the scepticism was founded on the Norwegian government being Labour and thus possibly contemplating nationalisation of the shipping companies after the war.

The Prime Minister rejected that suggestion, and in a cable in March 1941, he promised that all ships would be handed back to their owners as soon as possible when the war was over.

That was partly corrected after pressure from the London office in August 1940, but it damaged Lorentzen's position as head of Nortraship and was a recurring theme for his critics.

That resulted in an increasing number of Norwegian seamen taking land-based work in the US or changing to other countries' ships running in less dangerous areas.

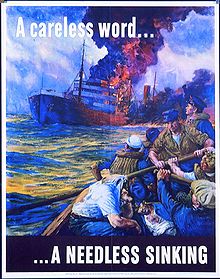

In 1940, the Norwegian vessels were unarmed, but defensive measures like guns against surfaced submarines and low-flying aircraft were slowly added.

The vessels also received degaussing against magnetic mines, and seamen were issued watertight survival suits if the ship had to be abandoned.

An important part of security was strict secrecy regarding routes and destinations, as made famous in the slogan "Loose lips sinks ships".

Nortraship's New York office tried to influence the US through the US Maritime Commission, arguing that Norwegian vessels were much needed for US import and export although only 30% of it was on US keel in 1939.6 After hard negotiations with both the British and US shipping administrations, a new tonnage agreement was signed on 10 October 1941, effectively letting Britain charter three fourths of all Norwegian vessels.

In the negotiations, Nortraship tried to secure the US dollar freight income, to obtain a more equal footing with the British in governing the Allied merchant fleet and to receive assurances regarding Norwegian shipping rights after the war.

A vessel carrying only "clean" oil would deteriorate faster and so an ongoing fight from both Nortraship offices was to get as many "dirty" cargoes as possible.

The US War Shipping Administration were more accommodating in the issue and let several Norwegian vessels change to "dirty" cargoes.

That created much bitterness, and the issue was not permanently solved until the Norwegian Parliament, in 1972, decided to pay an ex gratia sum, a total of 155 million NOK.

As Nortraship was a huge organisation, with tens of thousand of people working around the world during five years of war, there were normally internal problems.

The main ones were between the offices in New York and London, each led by determined shipowners: Øivind Lorentzen and Ingolf Hysing Olsen.