Nostradamus

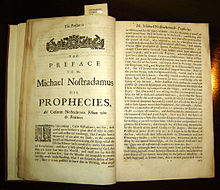

This is an accepted version of this page Michel de Nostredame (December 1503 – July 1566[1]), usually Latinised as Nostradamus,[a] was a French astrologer, apothecary, physician, and reputed seer, who is best known for his book Les Prophéties (published in 1555), a collection of 942[b] poetic quatrains allegedly predicting future events.

[10] Jaume's family had originally been Jewish, but his father, Cresquas, a grain and money dealer based in Avignon, had converted to Catholicism around 1459–60, taking the Christian name "Pierre" and the surname "Nostredame" (Our Lady), the saint on whose day his conversion was solemnised.

After little more than a year (when he would have studied the regular trivium of grammar, rhetoric and logic rather than the more advanced quadrivium of geometry, arithmetic, music, and astronomy/astrology), he was forced to leave Avignon when the university closed its doors during an outbreak of the plague.

He was expelled shortly afterwards by the student procurator, Guillaume Rondelet, when it was discovered that he had been an apothecary, a "manual trade" expressly banned by the university statutes, and had been slandering doctors.

It was mainly in response to the almanacs that the nobility and other prominent people from far away soon started asking for horoscopes and "psychic" advice from him, though he generally expected his clients to supply the birth charts on which these would be based, rather than calculating them himself as a professional astrologer would have done.

When obliged to attempt this himself on the basis of the published tables of the day, he frequently made errors and failed to adjust the figures for his clients' place or time of birth.

Feeling vulnerable to opposition on religious grounds,[29] he devised a method of obscuring his meaning by using "Virgilianised" syntax, word games and a mixture of other languages such as Greek, Italian, Latin, and Provençal.

Some accounts of Nostradamus's life state that he was afraid of being persecuted for heresy by the Inquisition, but neither prophecy nor astrology fell in this bracket, and he would have been in danger only if he had practised magic to support them.

The next morning he was reportedly found dead, lying on the floor next to his bed and a bench (Presage 141 [originally 152] for November 1567, as posthumously edited by Chavigny to fit what happened).

[35][25] He was buried in the local Franciscan chapel in Salon (part of it now incorporated into the restaurant La Brocherie) but re-interred during the French Revolution in the Collégiale Saint-Laurent, where his tomb remains to this day.

One was an extremely free translation (or rather a paraphrase) of The Protreptic of Galen (Paraphrase de C. GALIEN, sus l'Exhortation de Menodote aux estudes des bonnes Artz, mesmement Medicine), and in his so-called Traité des fardemens (basically a medical cookbook containing, once again, materials borrowed mainly from others), he included a description of the methods he used to treat the plague, including bloodletting, none of which apparently worked.

A manuscript normally known as the Orus Apollo also exists in the Lyon municipal library, where upwards of 2,000 original documents relating to Nostradamus are stored under the aegis of Michel Chomarat.

Their persistence in popular culture seems to be partly because their vagueness and lack of dating make it easy to quote them selectively after every major dramatic event and retrospectively claim them as "hits".

[43] Research suggests that much of his prophetic work paraphrases collections of ancient end-of-the-world prophecies (mainly Bible-based), supplemented with references to historical events and anthologies of omen reports, and then projects those into the future in part with the aid of comparative horoscopy.

His historical sources include easily identifiable passages from Livy, Suetonius' The Twelve Caesars, Plutarch and other classical historians, as well as from medieval chroniclers such as Geoffrey of Villehardouin and Jean Froissart.

This book had enjoyed considerable success in the 1520s, when it went through half a dozen editions, but did not sustain its influence, perhaps owing to its mostly Latin text (mixed with ancient Greek and modern French and Provençal),[45] Gothic script and many difficult abbreviations.

The latest research suggests that he may in fact have used bibliomancy for this—randomly selecting a book of history or prophecy and taking his cue from whatever page it happened to fall open at.

[S]ome of [the prophets] predicted great and marvelous things to come: [though] for me, I in no way attribute to myself such a title here.Not that I am foolish enough to claim to be a prophet.Given this reliance on literary sources, it is unlikely that Nostradamus used any particular methods for entering a trance state, other than contemplation, meditation and incubation.

[57] Many supporters do agree, for example, that he predicted the Great Fire of London, the French Revolution, the rise of Napoleon and of Adolf Hitler,[58][e] both world wars, and the nuclear destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

[57][28] Popular authors frequently claim that he predicted whatever major event had just happened at the time of each of their books' publication, such as the Apollo Moon landing in 1969, the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster in 1986, the death of Diana, Princess of Wales in 1997, and the September 11 attacks on the World Trade Center in 2001.

[57] Possibly the first of these books to become popular in English was Henry C. Roberts' The Complete Prophecies of Nostradamus of 1947, reprinted at least seven times during the next forty years, which contained both transcriptions and translations, with brief commentaries.

This served as the basis for the documentary The Man Who Saw Tomorrow and both did indeed mention possible generalised future attacks on New York (via nuclear weapons), though not specifically on the World Trade Center or on any particular date.

In 1992 one commentator who claimed to be able to contact Nostradamus under hypnosis even had him "interpreting" his own verse X.6 (a prediction specifically about floods in southern France around the city of Nîmes and people taking refuge in its collosse, or Colosseum, a Roman amphitheatre now known as the Arènes) as a prediction of an undated attack on the Pentagon, despite the historical seer's clear statement in his dedicatory letter to King Henri II that his prophecies were about Europe, North Africa and part of Asia Minor.

[61] With the exception of Roberts, these books and their many popular imitators were almost unanimous not merely about Nostradamus's powers of prophecy but also in inventing intriguing aspects of his purported biography: that he had been a descendant of the Israelite tribe of Issachar; he had been educated by his grandfathers, who had both been physicians to the court of Good King René of Provence; he had attended Montpellier University in 1525 to gain his first degree; after returning there in 1529, he had successfully taken his medical doctorate; he had gone on to lecture in the Medical Faculty there, until his views became too unpopular; he had supported the heliocentric view of the universe; he had travelled to the Habsburg Netherlands, where he had composed prophecies at the abbey of Orval; in the course of his travels, he had performed a variety of prodigies, including identifying future Pope, Sixtus V, who was then only a seminary monk.

He is credited with having successfully cured the Plague at Aix-en-Provence and elsewhere; he had engaged in scrying, using either a magic mirror or a bowl of water; he had been joined by his secretary Chavigny at Easter 1554; having published the first installment of his Prophéties, he had been summoned by Queen Catherine de' Medici to Paris in 1556 specifically in order to discuss with her his prophecy at quatrain I.35 that her husband King Henri II would be killed in a duel; he had examined the royal children at Blois; he had bequeathed to his son a "lost book" of his own prophetic paintings;[f] he had been buried standing up; and he had been found, when dug up at the French Revolution, to be wearing a medallion bearing the exact date of his disinterment.

Most of them had evidently been based on unsourced rumours relayed as fact by much later commentators, such as Jaubert (1656), Guynaud (1693) and Bareste (1840); on modern misunderstandings of the 16th-century French texts; or on pure invention.

Even the often-advanced suggestion that quatrain I.35 had successfully prophesied King Henry II's death did not actually appear in print for the first time until 1614, 55 years after the event.

[68][69] Skeptics such as James Randi suggest that his reputation as a prophet is largely manufactured by modern-day supporters who fit his words to events that have either already occurred or are so imminent as to be inevitable, a process sometimes known as "retroactive clairvoyance" (postdiction).

Meanwhile, some of the more recent sources listed (Lemesurier, Gruber, Wilson) have been particularly scathing about later attempts by some lesser-known authors and Internet enthusiasts to extract alleged hidden meanings from the texts, whether with the aid of anagrams, numerical codes, graphs or otherwise.