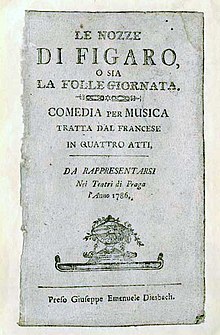

The Marriage of Figaro

The Marriage of Figaro came in first out of the 20 operas featured, with the magazine describing the work as being "one of the supreme masterpieces of operatic comedy, whose rich sense of humanity shines out of Mozart's miraculous score".

Beaumarchais's Mariage de Figaro, with its frank treatment of class conflict,[3] was at first banned in Vienna: Emperor Joseph II stated that "since the piece contains much that is objectionable, I therefore expect that the Censor shall either reject it altogether, or at any rate have such alterations made in it that he shall be responsible for the performance of this play and for the impression it may make", after which the Austrian Censor duly forbade performing the German version of the play.

It alludes to interference probably produced by paid hecklers, but praises the work warmly: Mozart's music was generally admired by connoisseurs already at the first performance, if I except only those whose self-love and conceit will not allow them to find merit in anything not written by themselves.

It heard many a bravo from unbiased connoisseurs, but obstreperous louts in the uppermost storey exerted their hired lungs with all their might to deafen singers and audience alike with their St!

[16]The Hungarian poet Ferenc Kazinczy was in the audience for a May performance, and later remembered the powerful impression the work made on him: [Nancy] Storace [see below], the beautiful singer, enchanted eye, ear, and soul.

This production was a tremendous success; the newspaper Prager Oberpostamtszeitung called the work "a masterpiece",[21] and said "no piece (for everyone here asserts) has ever caused such a sensation.

Dr. Bartolo is seeking revenge against Figaro for thwarting his plans to marry Rosina himself, and Count Almaviva has degenerated from the romantic youth of Barber, (a tenor in Paisiello's 1782 opera), into a scheming, bullying, skirt-chasing baritone.

Figaro happily measures the space where the bridal bed will fit while Susanna tries on her wedding bonnet (which she has sewn herself) in front of a mirror.

Figaro is quite pleased with their new room; Susanna far less so (Duettino: "Se a caso madama la notte ti chiama" – "If the Countess should call you during the night").

She is bothered by its proximity to the Count's chambers: it seems he has been making advances toward her and plans on exercising his droit du seigneur, the feudal right of a lord to bed a servant girl on her wedding night before her husband can sleep with her.

Bartolo, seeking revenge against Figaro for having facilitated the union of the Count and Rosina (in The Barber of Seville), agrees to represent Marcellina pro bono, and assures her, in comical lawyer-speak, that he can win the case for her (aria: "La vendetta" – "Vengeance").

Cherubino then arrives and after describing his emerging infatuation with all women, particularly with his "beautiful godmother" the Countess, (aria: "Non so più cosa son" – "I don't know anymore what I am") asks for Susanna's aid with the Count.

When Basilio starts to gossip about Cherubino's obvious attraction to the Countess, the Count angrily leaps from his hiding place (terzetto: "Cosa sento!"

Figaro gives Cherubino mocking advice about his new, harsh, military life from which all luxury, and especially women, will be totally excluded (aria: "Non più andrai" – "No more gallivanting").

After the song, the Countess, seeing Cherubino's military commission, notices that the Count was in such a hurry that he forgot to seal it with his signet ring (thus making it an official document).

The enraged Count draws his sword, promising to kill Cherubino on the spot, but when the closet door is opened, to their astonishment, they only find Susanna (Finale: "Esci omai, garzon malnato" – "Come out of there, you ill-born boy!").

Antonio adds that he tentatively identified the running man as Cherubino, but Figaro claims it was he himself who jumped out of the window, and pretends to have injured his foot while landing.

At the urging of the Countess, Susanna enters and gives a false promise to meet the Count later that night in the garden (duet: "Crudel!

Bartolo, overcome with emotion, agrees to marry Marcellina that evening in a double wedding (sextet: "Riconosci in questo amplesso" – "Recognize in this embrace").

His anger is quickly dispelled by Barbarina, who publicly recalls that he had once offered to give her anything she wanted in exchange for certain favors, and asks for Cherubino's hand in marriage.

He tells a tale of how he was given common sense by "Donna Flemma" ("Dame Prudence") and learned the importance of not crossing powerful people, (aria: "In quegli anni" – "In those years").

Figaro muses bitterly on the inconstancy of women (recitative and aria: "Tutto è disposto ... Aprite un po' quegli occhi" – "Everything is ready ... Open those eyes a little").

The Marriage of Figaro is scored for two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, two horns, two clarini, timpani, and strings; the recitativi secchi are accompanied by a keyboard instrument, usually a fortepiano or a harpsichord, often joined by a cello.

Two arias from act 4 are often omitted: one in which Marcellina regrets that people (unlike goats, sheep, or wild beasts) abuse their mates (Il capro e la capretta); and one in which Don Basilio tells how he saved himself from several dangers in his youth by using the skin of a donkey for shelter and camouflage (In quegli anni).

[32] Lorenzo Da Ponte wrote a preface to the first published version of the libretto, in which he boldly claimed that he and Mozart had created a new form of music drama: In spite ... of every effort ... to be brief, the opera will not be one of the shortest to have appeared on our stage, for which we hope sufficient excuse will be found in the variety of threads from which the action of this play [i.e. Beaumarchais's] is woven, the vastness and grandeur of the same, the multiplicity of the musical numbers that had to be made in order not to leave the actors too long unemployed, to diminish the vexation and monotony of long recitatives, and to express with varied colours the various emotions that occur, but above all in our desire to offer as it were a new kind of spectacle to a public of so refined a taste and understanding.

[33]Charles Rosen, in The Classical Style, proposes to take Da Ponte's words quite seriously, noting the "richness of the ensemble writing",[34] which carries forward the action in a far more dramatic way than recitatives would.

Rosen also suggests that the musical language of the classical style was adapted by Mozart to convey the drama; many sections of the opera resemble sonata form.

The synthesis of accelerating complexity and symmetrical resolution which was at the heart of Mozart's style enabled him to find a musical equivalent for the great stage works which were his dramatic models.

perchè finora" in his Fantaisie dramatique sur des Airs favoris, Bijoux à la Malibran for piano, Op.

In 1819, Henry R. Bishop wrote an adaptation of the opera in English, translating from Beaumarchais's play and re-using some of Mozart's music, while adding some of his own.