NuSTAR

For this two conical approximation Wolter telescope design optics with 10.15 m (33.3 ft) focal length are held at the end of a long deployable mast.

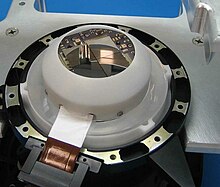

[18][19] The optics were produced, at Goddard Space Flight Center, by heating thin (210 μm (0.0083 in)) sheets of flexible glass in an oven so that they slumped over precision-polished cylindrical quartz mandrels of the appropriate radius.

The shells were then assembled, at the Nevis Laboratories of Columbia University, using graphite spacers machined to constrain the glass to the conical shape, and held together by epoxy.

[20] The expected point spread function for the flight mirrors is 43 arcseconds, giving a spot size of about two millimeters at the focal plane; this is unprecedentedly good resolution for focusing hard X-ray optics, though it is about one hundred times worse than the best resolution achieved at longer wavelengths by the Chandra X-ray Observatory.

Each focusing optic has its own focal plane module, consisting of a solid state cadmium zinc telluride (CdZnTe) pixel detector[21] surrounded by a cesium iodide (CsI) anti-coincidence shield.

The cadmium zinc telluride (CdZnTe) detectors are state of the art room temperature semiconductors that are very efficient at turning high energy photons into electrons.

The electrons are digitally recorded using custom application-specific integrated circuits (ASICs) designed by the NuSTAR California Institute of Technology (CalTech) Focal Plane Team.

The crystal shields, grown by Saint-Gobain, register high energy photons and cosmic rays which cross the focal plane from directions other than the along the NuSTAR optical axis.

In February 2013, NASA revealed that NuSTAR, along with the XMM-Newton space observatory, has measured the spin rate of the supermassive black hole at the center of the galaxy NGC 1365.

This caused inner portions of the black hole's accretion disk to be illuminated with X-rays, allowing this elusive region to be studied by astronomers for spin rates.

The NuSTAR map of Cassiopeia A shows the titanium-44 isotope concentrated in clumps at the remnant's center and points to a possible solution to the mystery of how the star exploded.

The Stanford University team of scientists that led the study concluded that this change was directly attributable to radiation from the flash reflecting off of the accretion disk on the opposing side of the black hole.

[32][33] In April 6th of 2023, the NuSTAR team confirmed that neutron star M82 X-2 was emitting more radiation than was physically thought possible due to the Eddington limit, officially labeling it as an Ultraluminous X-ray source (ULX).