Nuclear holocaust

Some scientists, such as Alan Robock, have speculated that a thermonuclear war could result in the end of modern civilization on Earth, in part due to a long-lasting nuclear winter.

[2] Early Cold War-era studies suggested that billions of humans would survive the immediate effects of nuclear blasts and radiation following a global thermonuclear war.

[7] The English word "holocaust", derived from the Greek term "holokaustos" meaning "completely burnt", refers to great destruction and loss of life, especially by fire.

[8][9] One early use of the word "holocaust" to describe an imagined nuclear destruction appears in Reginald Glossop's 1926 novel The Orphan of Space: "Moscow ... beneath them ... a crash like a crack of Doom!

"[10] In the novel, an atomic weapon is planted in the office of the Soviet dictator, who, with German help and Chinese mercenaries, is preparing the takeover of Western Europe.

[16][17][18] The Bulletin advanced their symbolic Doomsday Clock in 2015, citing among other factors "a nuclear arms race resulting from modernization of huge arsenals".

[29] Technically the risk may not be zero, as the climatic effects of nuclear war are uncertain and could theoretically be larger, but also smaller, than current models suggest.

[30] Physicist Leo Szilard warned in the 1950s that a deliberate doomsday device could be constructed by surrounding powerful hydrogen bombs with a massive amount of cobalt.

Cobalt has a half-life of five years, and its global fallout might, some physicists have posited, be able to clear out all human life via lethal radiation intensity.

In the early 1980s, scientists began to consider the effects of smoke and soot arising from burning wood, plastics, and petroleum fuels in nuclear-devastated cities.

It was speculated that the intense heat would carry these particulates to extremely high altitudes where they could drift for weeks and block out all but a fraction of the sun's light.

[33] A landmark 1983 study by the so-called TTAPS team (Richard P. Turco, Owen Toon, Thomas P. Ackerman, James B. Pollack and Carl Sagan) was the first to model these effects and coined the term "nuclear winter.

The changes they found were also much longer-lasting than previously thought, because their new model better represented entry of soot aerosols in the upper stratosphere, where precipitation does not occur, and therefore clearance was on the order of 10 years.

Additionally, the analysis showed a 10% drop in average global precipitation, with the largest losses in the low latitudes due to failure of the monsoons.

A 2008 study found that a regional nuclear weapons exchange could create a near-global ozone hole, triggering human health problems and impacting agriculture for at least a decade.

[37] This effect on the ozone would result from heat absorption by soot in the upper stratosphere, which would modify wind currents and draw in ozone-destroying nitrogen oxides.

[39][40] Several independent studies[citation needed] show corroborated conclusions that agricultural outputs would be significantly reduced for years by climatic changes driven by nuclear wars.

In 2013, the US House of Representatives considered the "Secure High-voltage Infrastructure for Electricity from Lethal Damage Act" that would provide surge protection for some 300 large transformers around the country.

A fast increase of global background radiation, peaking in 1963 (the Bomb pulse) urged, among other things states to sign bans on nuclear weapons testing.

[55] The impetus for Schell's work, according to physicist Brian Martin, was: The implicit premise [...] that if people are not taking action on the issue, they must not perceive it as threatening enough.

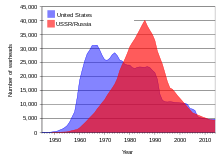

Indeed, Schell explicitly advocates use of the fear of extinction as the basis for inspiring the "complete rearrangement of world politics" (p. 221)[55]The belief in "overkill" is also commonly encountered, with an example being the following statement made by nuclear disarmament activist Philip Noel-Baker in 1971: "Both the US and the Soviet Union now possess nuclear stockpiles large enough to exterminate mankind three or four – some say ten – times over".

By comparison – in the timeline of volcanism on Earth – the 1815 eruption of Mount Tambora exploded with a force of roughly 30,000 megatons,[57] and ejected 160 km3 (38 cu mi) of mostly rock and tephra,[58] which included 120 million tonnes of sulfur dioxide as an upper estimate, turning 1816 into the "year without a summer" due to the levels of global dimming sulfate aerosols and ash expelled.

[59] The larger Mount Toba eruption, which occurred approximately 74,000 years ago, produced an estimated 2,800 km3 (670 cu mi) of tephra[60] and 6,000 million tonnes (6.6×109 short tons) of sulfur dioxide,[61][62] with a possible explosion force of 20,000,000 megatons (Mt) of TNT, forming Lake Toba and reducing the human population to mere tens of thousands.

The Chicxulub impact, connected with the extinction of the dinosaurs, corresponds to at least 70,000,000 Mt of energy, which is roughly 7000 times the combined maximum arsenal of the US and Soviet Union.