Nuclear fuel

It can be made from enriched uranium hexafluoride by reacting with ammonia to form a solid called ammonium diuranate, (NH4)2U2O7.

As of 2015, MOX fuel is made in France at the Marcoule Nuclear Site, and to a lesser extent in Russia at the Mining and Chemical Combine, India and Japan.

Reprocessing of spent commercial-reactor nuclear fuel has not been permitted in the United States due to nonproliferation considerations.

All other reprocessing nations have long had nuclear weapons from military-focused research reactor fuels except for Japan.

It can be made inherently safe as thermal expansion of the metal alloy will increase neutron leakage.

Much of what is known about uranium carbide is in the form of pin-type fuel elements for liquid metal fast reactors during their intense study in the 1960s and 1970s.

In addition, because of the absence of oxygen in this fuel (during the course of irradiation, excess gas pressure can build from the formation of O2 or other gases) as well as the ability to complement a ceramic coating (a ceramic-ceramic interface has structural and chemical advantages), uranium carbide could be the ideal fuel candidate for certain Generation IV reactors such as the gas-cooled fast reactor.

This advantage was conclusively demonstrated repeatedly as part of a weekly shutdown procedure during the highly successful Molten-Salt Reactor Experiment from 1965 to 1969.

The liquid fuel for the molten salt reactor was a mixture of lithium, beryllium, thorium and uranium fluorides: LiF-BeF2-ThF4-UF4 (72-16-12-0.4 mol%).

The dual fluid reactor (DFR) has a variant DFR/m which works with eutectic liquid metal alloys, e.g. U-Cr or U-Fe.

Stainless steel was used in the past, but most reactors now use a zirconium alloy which, in addition to being highly corrosion-resistant, has low neutron absorption.

It is made of a corrosion-resistant material with low absorption cross section for thermal neutrons, usually Zircaloy or steel in modern constructions, or magnesium with small amount of aluminium and other metals for the now-obsolete Magnox reactors.

For example, the highly reactive alkali metal caesium which reacts strongly with water, producing hydrogen, and which is among the more common fission products.

The uranium oxide is dried before inserting into the tubes to try to eliminate moisture in the ceramic fuel that can lead to corrosion and hydrogen embrittlement.

The Zircaloy tubes are pressurized with helium to try to minimize pellet-cladding interaction which can lead to fuel rod failure over long periods.

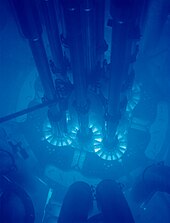

This is primarily done to prevent local density variations from affecting neutronics and thermal hydraulics of the reactor core.

Various other nuclear fuel forms find use in specific applications, but lack the widespread use of those found in BWRs, PWRs, and CANDU power plants.

Magnox alloy consists mainly of magnesium with small amounts of aluminium and other metals—used in cladding unenriched uranium metal fuel with a non-oxidising covering to contain fission products.

TRISO fuel particles were originally developed in the United Kingdom as part of the Dragon reactor project.

This mechanism compensates for the accumulation of undesirable neutron poisons which are an unavoidable part of the fission products, as well as normal fissile fuel "burn up" or depletion.

Following the Chernobyl accident, the enrichment of fuel was changed from 2.0% to 2.4%, to compensate for control rod modifications and the introduction of additional absorbers.

These concerns became more prominent after the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster in Japan, in particular regarding light-water reactor (LWR) fuels performance under accident conditions.

Despite the fact that the used fuel can be cracked, it is very insoluble in water, and is able to retain the vast majority of the actinides and fission products within the uranium dioxide crystal lattice.

The radiation hazard from spent nuclear fuel declines as its radioactive components decay, but remains high for many years.

Materials in a high-radiation environment (such as a reactor) can undergo unique behaviors such as swelling[21] and non-thermal creep.

According to the International Nuclear Safety Center[22] the thermal conductivity of uranium dioxide can be predicted under different conditions by a series of equations.

It has a half-life of 87.7 years, reasonable energy density, and exceptionally low gamma and neutron radiation levels.

This fuel provides phenomenally huge energy density, (a single gram of polonium-210 generates 140 watts thermal) but has limited use because of its very short half-life and gamma production, and has been phased out of use for this application.

Many other elements can be fused together, but the larger electrical charge of their nuclei means that much higher temperatures are required.

[24] Deuterium and tritium are both considered first-generation fusion fuels; they are the easiest to fuse, because the electrical charge on their nuclei is the lowest of all elements.