Nuclear medicine

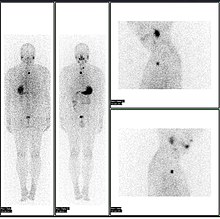

In addition, there are nuclear medicine studies that allow imaging of the whole body based on certain cellular receptors or functions.

Also, contrast-enhancement techniques in both CT and MRI show regions of tissue that are handling pharmaceuticals differently, due to an inflammatory process.

Diagnostic tests in nuclear medicine exploit the way that the body handles substances differently when there is disease or pathology present.

In some centers, the nuclear medicine scans can be superimposed, using software or hybrid cameras, on images from modalities such as CT or MRI to highlight the part of the body in which the radiopharmaceutical is concentrated.

The fusion imaging technique in nuclear medicine provides information about the anatomy and function, which would otherwise be unavailable or would require a more invasive procedure or surgery.

Giving larger radiation exposures can reduce the noise in an image and make it more photographically appealing, but if the clinical question can be answered without this level of detail, then this is inappropriate.

As a result, the radiation dose from nuclear medicine imaging varies greatly depending on the type of study.

Some nuclear medicine procedures require special patient preparation before the study to obtain the most accurate result.

In nuclear medicine therapy, the radiation treatment dose is administered internally (e.g. intravenous or oral routes) or externally direct above the area to treat in form of a compound (e.g. in case of skin cancer).

The radiopharmaceuticals used in nuclear medicine therapy emit ionizing radiation that travels only a short distance, thereby minimizing unwanted side effects and damage to noninvolved organs or nearby structures.

Most nuclear medicine therapies can be performed as outpatient procedures since there are few side effects from the treatment and the radiation exposure to the general public can be kept within a safe limit.

[6] The origins of this medical idea date back as far as the mid-1920s in Freiburg, Germany, when George de Hevesy made experiments with radionuclides administered to rats, thus displaying metabolic pathways of these substances and establishing the tracer principle.

Nuclear medicine gained public recognition as a potential specialty when on May 11, 1946, an article in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) by Massachusetts General Hospital's Dr. Saul Hertz and Massachusetts Institute of Technology's Dr. Arthur Roberts, described the successful use of treating Graves' Disease with radioactive iodine (RAI) was published.

[10] brought further development in the field describing a successful treatment of a patient with thyroid cancer metastases using radioiodine (I-131).

By the early 1960s, in southern Scandinavia, Niels A. Lassen, David H. Ingvar, and Erik Skinhøj developed techniques that provided the first blood flow maps of the brain, which initially involved xenon-133 inhalation;[12] an intra-arterial equivalent was developed soon after, enabling measurement of the local distribution of cerebral activity for patients with neuropsychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia.

It allowed them to construct images reflecting brain activation from speaking, reading, visual or auditory perception and voluntary movement.

The development of single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), around the same time, led to three-dimensional reconstruction of the heart and establishment of the field of nuclear cardiology.

More recent developments in nuclear medicine include the invention of the first positron emission tomography scanner (PET).

[citation needed] PET and PET/CT imaging experienced slower growth in its early years owing to the cost of the modality and the requirement for an on-site or nearby cyclotron.

However, an administrative decision to approve medical reimbursement of limited PET and PET/CT applications in oncology has led to phenomenal growth and widespread acceptance over the last few years, which also was facilitated by establishing 18F-labelled tracers for standard procedures, allowing work at non-cyclotron-equipped sites.

Z = atomic number, the number of protonsT1/2 = half-lifedecay = mode of decay photons = principal photon energies in kilo-electron volts, keV, (abundance/decay) β = beta maximum energy in kilo-electron volts, keV, (abundance/decay) β+ = β+ decay; β− = β− decay; IT = isomeric transition; ec = electron capture * X-rays from progeny, mercury, Hg A typical nuclear medicine study involves administration of a radionuclide into the body by intravenous injection in liquid or aggregate form, ingestion while combined with food, inhalation as a gas or aerosol, or rarely, injection of a radionuclide that has undergone micro-encapsulation.

Most diagnostic radionuclides emit gamma rays either directly from their decay or indirectly through electron–positron annihilation, while the cell-damaging properties of beta particles are used in therapeutic applications.

The radiation dose delivered to a patient in a nuclear medicine investigation, though unproven, is generally accepted to present a very small risk of inducing cancer.

For example, in the US, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) have guidelines in place for hospitals to follow.

Groups like International Commission on Radiological Protection have published information on how to manage the release of patients from a hospital with unsealed radionuclides.