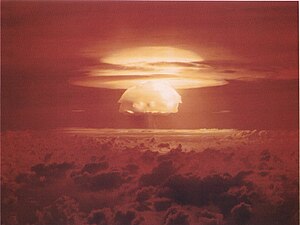

Nuclear testing at Bikini Atoll

The United States and its allies were engaged in a Cold War nuclear arms race with the Soviet Union to build more advanced bombs from 1947 until 1991.

Despite the promises made by authorities, these and further nuclear tests (Redwing in 1956 and Hardtack in 1958) rendered Bikini unfit for habitation, contaminating the soil and water, making subsistence farming and fishing too dangerous.

In February 1946, the United States government forced the 167 Micronesian inhabitants of the atoll to temporarily relocate so that testing could begin on atomic bombs.

[12] No one lived on Rongerik because it had an inadequate water and food supply, and also due to traditional beliefs that the island was haunted by the Demon Girls of Ujae.

[15] Seabees built bunkers, floating dry docks,[16] 75 ft (23 m) steel towers for cameras and recording instruments,[17] and other facilities on the island to support the servicemen.

The "club" was little more than a small open-air building which served alcohol to servicemen and provided outdoor entertainment, including a ping pong table.

A few minutes after the detonation, blast debris began to fall on Eneu/Enyu Island on Bikini Atoll where the crew who fired the device were located.

Their Geiger counters detected the unexpected fallout, and they were forced to take shelter indoors for a number of hours before it was safe for an airlift rescue operation.

[27] The fallout gradually dispersed around the globe, depositing traces of radioactive material in Australia, India, Japan, and parts of the United States of America and Europe.

[29][30][31] Six days after the Castle Bravo test, the government set up a secret project to study the medical effects of the weapon on the residents of the Marshall Islands.

[32] The United States was subsequently accused of using the inhabitants as medical research subjects without obtaining their consent to study the effects of nuclear exposure.

[citation needed] Ninety minutes after the detonation, 23 crew members of the Japanese fishing boat the Daigo Fukuryū Maru ("Lucky Dragon No.

One fisherman died about six months later while under doctor supervision; his cause of death was ruled a pre-existing liver cirrhosis compounded by a hepatitis C infection.

[34][better source needed] The majority of medical experts believe that the crew members were infected with hepatitis C through blood transfusions during part of their acute radiation syndrome treatment.

[4] President Lyndon B. Johnson promised the 540 Bikini Atoll families living on Kili and other islands in June 1968 that they would be able to return to their home, based on scientific advice that the radiation levels were sufficiently reduced.

But the Atomic Energy Commission learned that the coconut crabs, an essential food source, retained high levels of radioactivity and could not be eaten.

The records obtained by the Marshallese Nuclear Claims Tribunal later revealed that Dr. Robert Conard, head of Brookhaven National Laboratory (BNL)'s medical team in the Marshall Islands, understated the risk of returning to the atoll.

[45] The special International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) Bikini Advisory Group determined in 1997 that it was "safe to walk on all of the islands" and that the residual radioactivity was "not hazardous to health at the levels measured".

They further stated that "the main radiation risk would be from the food", but they also added that "eating coconuts or breadfruit from Bikini Island occasionally would be no cause for concern".

Scientists reply that removing the soil would rid the island of cesium-137, but it would also severely damage the environment, turning the atoll into a virtual wasteland of windswept sand.

The population is growing at a four percent growth rate, so increasing numbers are taking advantage of terms in the Marshall Islands' Compact of Free Association that allow them to obtain jobs in the United States.

[21] Stanford University professor Steve Palumbi led a study in 2017 that reported on ocean life that seems highly resilient to the effects of radiation poisoning.

"[11] Both corals and long-lived animals such as coconut crabs should be vulnerable to radiation-induced cancers,[56] and understanding how they have thrived might lead to discoveries about preserving DNA.

[57][58] PBS documented field work undertaken by Palumbi and his graduate student Elora López on Bikini Atoll for the second episode ("Violent") of their series Big Pacific.

[56][59] The episode explored "species, natural phenomena and behaviors of the Pacific Ocean" and the way that the team is using DNA sequencing to study the rate and pattern of any mutations.

[58] López suggested possible explanations for the health of the marine life to The Stanford Daily, such as a mechanism for DNA repair that is superior to that possessed by humans, or a method of maintaining a genome in the face of nuclear radiation.

[56][58] Pambuli and his team have focused on the hubcap-sized crabs, as their coconut diet is contaminated with radioactive caesium-137 from ground water,[57][60] and on the corals, because both have longer life spans that allow the scientists "to delve into what effect the radiation exposure has had on the animals' DNA after building up in their systems for many years.

"[11] Bikini Atoll remains uninhabitable for humans due to what United Nations reporter Călin Georgescu described as "near-irreversible environmental contamination".

[6] The residents of Rongelap and Utirik atolls were exposed to high levels of radiation, the heaviest of which was in the form of pulverized surface coral from the detonation.

The greatest exposure is from consuming contaminated food like coconut, pandanus, papaya, banana, arrowroot, taro, limes, breadfruit, and the ducks, pigs, and chickens raised on the islands.