Nuclear thermal rocket

In an NTR, a working fluid, usually liquid hydrogen, is heated to a high temperature in a nuclear reactor and then expands through a rocket nozzle to create thrust.

The external nuclear heat source theoretically allows a higher effective exhaust velocity and is expected to double or triple payload capacity compared to chemical propellants that store energy internally.

[1] In May 2022 DARPA issued an RFP for the next phase of their Demonstration Rocket for Agile Cislunar Operations (DRACO) nuclear thermal engine program.

[3] In July 2023, Lockheed Martin was awarded the contract to build the spacecraft and BWX Technologies (BWXT) will develop the nuclear reactor.

In 1944, Stanisław Ulam and Frederic de Hoffmann contemplated the idea of controlling the power of nuclear explosions to launch space vehicles.

[9] After World War II, the U.S. military started the development of intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBM) based on the German V-2 rocket designs.

[21][20] In 1948 and 1949, physicist Leslie Shepherd and rocket scientist Val Cleaver produced a series of groundbreaking scientific papers that considered how nuclear technology might be applied to interplanetary travel.

As with all thermal rocket designs, the specific impulse produced is proportional to the square root of the temperature to which the working fluid (reaction mass) is heated.

Combined with the large tanks necessary for liquid hydrogen storage, this means that solid core nuclear thermal engines are best suited for use in orbit outside Earth's gravity well, not to mention avoiding the radioactive contamination that would result from atmospheric use[1] (if an "open-cycle" design was used, as opposed to a lower-performance "closed cycle" design where no radioactive material was allowed to escape with the rocket propellant.

[citation needed] From 1987 through 1991, the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI) Office funded Project Timberwind, a non-rotating nuclear thermal rocket based on particle bed technology.

For instance, during a high-thrust phase of flight, like exiting a low earth orbit, the engine could operate continually and provide an Isp similar to that of traditional solid-core design.

One possible solution is to rotate the fuel/fluid mixture at very high speeds to force the higher-density fuel to the outside, but this would expose the reactor pressure vessel to the maximum operating temperature while adding mass, complexity, and moving parts.

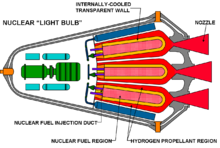

This is a modification to the liquid-core design which uses rapid circulation of the fluid to create a toroidal pocket of gaseous uranium fuel in the middle of the reactor, surrounded by hydrogen.

In this case, the fuel does not touch the reactor wall at all, so temperatures could reach several tens of thousands of degrees, which would allow specific impulses of 3000 to 5000 seconds (30 to 50 kN·s/kg).

To enable cooperation with the AEC and keep classified information compartmentalized, the Space Nuclear Propulsion Office (SNPO) was formed at the same time.

Unlike the AEC work, which was intended to study the reactor design itself, NERVA's goal was to produce a real engine that could be deployed on space missions.

The Small Nuclear Rocket Engine, or SNRE, was designed at the Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL) for upper stage use, both on uncrewed launchers and the Space Shuttle.

[citation needed] The KIWI B series was fueled by tiny uranium dioxide (UO2) spheres embedded in a low-boron graphite matrix and coated with niobium carbide.

The fuel bundle erosion and cracking problems were improved but never completely solved, despite promising materials work at the Argonne National Laboratory.

NERVA NRX/XE produced the baseline 334 kN (75,000 lbf) thrust that Marshall Space Flight Center required in Mars mission plans.

The last NRX firing lost 17 kg (38 lb) of nuclear fuel in 2 hours of testing, which was judged sufficient for space missions by SNPO.

Fission-fragment rocket using 242mAm was proposed by George Chapline[43] at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) in 1988, who suggested propulsion based on the direct heating of a propellant gas by fission fragments generated by a fissile material.

Ronen et al.[44] demonstrate that 242mAm can maintain sustained nuclear fission as an extremely thin metallic film, less than 1/1000 of a millimeter thick.

Ronen's group at the Ben-Gurion University of the Negev further showed that nuclear fuel based on 242mAm could speed space vehicles from Earth to Mars in as little as two weeks.

[60][61] Current solid-core nuclear thermal rocket designs are intended to greatly limit the dispersion and break-up of radioactive fuel elements in the event of a catastrophic failure.

[63] In historical ground testing, NTRs proved to be at least twice as efficient as the most advanced chemical engines, which would allow for quicker transfer time and increased cargo capacity.

[67][68][70][71] In 2017, NASA continued research and development on NTRs, designing for space applications with civilian approved materials, with a three-year, US$18.8 million contract.

In addition to the U.S. military, NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine has also expressed interest in the project and its potential applications for a future mission to Mars.

[77] In July 2023, U.S. agencies announced that Lockheed Martin had been awarded a $499 million contract to assemble the experimental nuclear thermal reactor vehicle (X-NTRV) and its engine.

[citation needed] It is considered unlikely that a reactor's fuel elements would be spread over a wide area, as they are composed of materials such as carbon composites or carbides and are normally coated with zirconium hydride.