Nuclear weapon yield

The explosive yield of a nuclear weapon is the amount of energy released such as blast, thermal, and nuclear radiation, when that particular nuclear weapon is detonated, usually expressed as a TNT equivalent (the standardized equivalent mass of trinitrotoluene which, if detonated, would produce the same energy discharge), either in kilotonnes (kt—thousands of tonnes of TNT), in megatonnes (Mt—millions of tonnes of TNT), or sometimes in terajoules (TJ).

[9] Most artificial non-nuclear explosions are considerably smaller than even what are considered to be very small nuclear weapons.

This effect results from the fact that destructive power of a single warhead on land scales approximately only as the cube root of its yield, due to blast "wasted" over a roughly hemispherical blast volume, while the strategic target is distributed over a circular land area with limited height and depth.

In order to maximize yield efficiency one must make sure to assemble the critical mass correctly, as well as implementing instruments such as tampers or initiators in the design.

Yields of nuclear explosions can be very hard to calculate, even using numbers as rough as in the kilotonne or megatonne range (much less down to the resolution of individual terajoules).

Yields can also be inferred in a number of other remote sensing ways, including scaling law calculations based on blast size, infrasound, fireball brightness (Bhangmeter), seismographic data (CTBTO),[17] and the strength of the shock wave.

Enrico Fermi famously made a (very) rough calculation of the yield of the Trinity test by dropping small pieces of paper in the air and measuring how far they were moved by the blast wave of the explosion; that is, he found the blast pressure at his distance from the detonation in pounds per square inch, using the deviation of the papers' fall away from the vertical as a crude blast gauge/barograph, and then with pressure X in psi, at distance Y, in miles figures, he extrapolated backwards to estimate the yield of the Trinity device, which he found was about 10 kilotonnes of blast energy.

I tried to estimate its strength by dropping from about six feet small pieces of paper before, during, and after the passage of the blast wave.

Since, at the time, there was no wind[,] I could observe very distinctly and actually measure the displacement of the pieces of paper that were in the process of falling while the blast was passing.

The shift was about 2 1/2 meters, which, at the time, I estimated to correspond to the blast that would be produced by ten thousand tonnes of TNT.

The paper is moved 2.5 meters by the wave, so the effect of the Trinity device is to displace a hemispherical shell of air of volume 2.5 m × 2π(16 km)2.

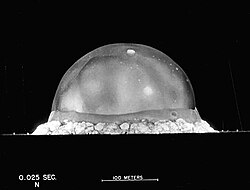

[quantify] A good approximation of the yield of the Trinity test device was obtained in 1950 by the British physicist G. I. Taylor from simple dimensional analysis and an estimation of the heat capacity for very hot air.

Taylor noted that the radius R of the blast should initially depend only on the energy E of the explosion, the time t after the detonation, and the density ρ of the air.

Using the picture of the Trinity test shown here (which had been publicly released by the U.S. government and published in Life magazine), using successive frames of the explosion, Taylor found that R5/t2 is a constant in a given nuclear blast (especially between 0.38 ms, after the shock wave has formed, and 1.93 ms, before significant energy is lost by thermal radiation).

Where these data are not available, as in a number of cases, precise yields have been in dispute, especially when they are tied to questions of politics.

The weapons used in the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, for example, were highly individual and very idiosyncratic designs, and gauging their yield retrospectively has been quite difficult.

The Hiroshima bomb, "Little Boy", is estimated to have been between 12 and 18 kilotonnes of TNT (50 and 75 TJ) (a 20% margin of error), while the Nagasaki bomb, "Fat Man", is estimated to be between 18 and 23 kilotonnes of TNT (75 and 96 TJ) (a 10% margin of error).

Other disputed yields have included the massive Tsar Bomba, whose yield was claimed between being "only" 50 megatonnes of TNT (210 PJ) or at a maximum of 57 megatonnes of TNT (240 PJ) by differing political figures, either as a way for hyping the power of the bomb or as an attempt to undercut it.