Nùng people

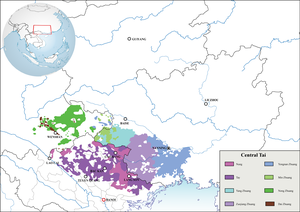

The Nùng (pronounced as noong [nuːŋ]) are a Central Tai-speaking ethnic group living primarily in northeastern Vietnam and southwestern Guangxi.

[10] The Nung (Nong in Pinyin transcription as referred to above) were a branch of the proto-Zhuang peoples who had a political relationship with Nan Zhao, and its successor, Dali.

By the early Song, they ruled over an area known as Temo, which stretched from modern Wenshan Zhuang and Miao Autonomous Prefecture in the west to Jingxi in the east and Guangyuanzhou (Quảng Nguyên, now Cao Bằng province[14]) in the south.

[15] Emperor Taizong of Song (r. 976-997) bestowed special favors on Nong leadership, acknowledging that they had succeeded the Huang in the Zuo River region.

It is not known when he was born, but a memorial in early 977 states that the "peaceful and generous" leader Nong Minfu of Guangyuanzhou had established himself over ten neighboring villages with the support of Southern Han (907-971).

[16] The Song bestowed the titles "minister of works" (sigong) and "grand master of splendid happiness bearing the golden pocket with purple trimming" (jinzi guanglu daifu) on Minfu.

These titles were passed onto Minfu's son, Nong Quanfu (Zhuang: Nungz Cienzfuk, Vietnamese: Nùng Tồn Phúc).

[12] Such preferential treatment was viewed with anger in Đại Cồ Việt, which attacked a Song garrison in 1004 after it held a banquet for a Nong chieftain.

[19] In 1035, Quanfu declared the founding of the Kingdom of Longevity (Changsheng Guo 長生國) and took for himself the exalted title "Luminous and Sage Emperor" (Zhaosheng Huangdi 昭聖皇帝) while A Nong became the "Enlightened and Virtuous Empress" (Mingde Huanghou 明德皇后).

The local prefect of Tianzhou requested assistance from Yongzhou to deal with the rebellion, but officials there appear to have feared involvement and refused to offer aid.

He was held prisoner for a year before he was released with an honorary title and given control of Guangyuan, Leihuo, Ping'an, Pinpo, and Silang in return for a share of their natural resources, particularly gold.

In 1052, Zhigao proclaimed the establishment of the Kingdom of the Great South (Danan Guo)[32] and granted himself the title of Benevolent and Kind Emperor (Renhui Huangdi).

He gathered 31,000 men and 32 generals, including Fanluo tribal cavalry from the northwest that "were able to ascend and descend mountains as though walking on level ground.

The Song infantry hacked at the Zhuang shields with heavy swords and axes while the Fanluo cavalry attacked their wings, breaking their ranks.

These Tai-speaking communities lived in the mountainous areas of Việt Bắc and most of their interaction with Viets was through the Các Lái, Kinh (Vietnamese) merchants who had obtained government licenses for trade in the uplands in return for tribute to the court.

After the Lam Sơn uprising which ended the Ming occupation, the Viet ruler Lê Lợi consolidated support from border communities by acknowledging a variety of local deities.

The Nùng became increasingly numerous in the region, and were spread out through a long stretch of the Vietnamese northern border from Lạng Sơn to Cao Bằng.

He quickly took control of Cao Bằng, Tuyên Quang, Thái Nguyên and Lạng Sơn provinces, aiming to create a separate Tày-Nùng state in the northern region of Vietnam.

[46] The period from the Taiping Rebellion (1850–64) to the early twentieth century was marked by continual waves of immigration by Zhuang/Nùng peoples from China into Vietnam.

These waves were a result of the continuous drought of Guangxi which made the thinly occupied lands of northern Vietnam an attractive alternative habitation.

[40] The French colonists saw this Nùng predominance as a threat, and found it convenient at that time to re-assert the primacy of the Vietnamese administrative system in the region.

[40] The French colonizers of the Tonkin Protectorate also saw the Nùng as potential converts to the colonial order and portrayed them as oppressed minorities who had suffered under Chinese and Viet rule.

According to a 1908 military dispatch by Commandant LeBlond, they had been "subjugated and held ransom during many long centuries, sometimes by the one, sometimes by the other, the [Nùng] race has become flexible and is frequently able to ascertain the stronger [neighbor], to which it would turn instinctively.

Although the Democratic Republic of Vietnam supervised state-sponsored migration to upland areas, the north did not experience a massive influx of Kinh Viets, so the ethnic balance around the Nùng Trí Cao temples remained fairly consistent.

However the Viet Bac Autonomous Zone in which the Nùng and Tày were most numerous was revoked by Lê Duẩn and the government pursued a policy of forced assimilation of minorities into Vietnamese culture.

All education was conducted in the Vietnamese language, traditional customs were discouraged or outlawed, and minority people were moved from their villages into government settlements.

References to "King Nùng" who had "raised high the banner proclaiming independence" have been replaced with floral patterns and pictures of horses, generic symbols associated with local heroes.

[55][51] When the Nùng moved into Vietnam from Guangxi during the 12th and 13th centuries, they developed slash-and-burn agriculture and worked on terraced hillsides, tending rice paddies and using water wheels for irrigation.

The Nùng engage in similar forms of agriculture today, using their gardens to grow a variety of vegetables, corn, peanuts, and fruits such as tangerines, persimmons, anise and other spices, and bamboo as cash crops.

[58] In Vietnam, the Tay and Nùng people can no longer read Chinese and write the pronunciation of the characters next to them in the Vietnamese alphabet for their ritual manuscripts.