Nyquist–Shannon sampling theorem

The theorem states that the sample rate must be at least twice the bandwidth of the signal to avoid aliasing.

Strictly speaking, the theorem only applies to a class of mathematical functions having a Fourier transform that is zero outside of a finite region of frequencies.

Intuitively we expect that when one reduces a continuous function to a discrete sequence and interpolates back to a continuous function, the fidelity of the result depends on the density (or sample rate) of the original samples.

The theorem also leads to a formula for perfectly reconstructing the original continuous-time function from the samples.

In some cases (when the sample-rate criterion is not satisfied), utilizing additional constraints allows for approximate reconstructions.

contains no frequencies higher than B hertz, then it can be completely determined from its ordinates at a sequence of points spaced less than

Practical digital-to-analog converters produce neither scaled and delayed sinc functions, nor ideal Dirac pulses.

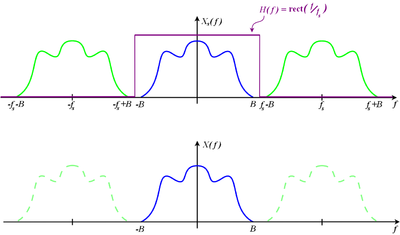

Instead they produce a piecewise-constant sequence of scaled and delayed rectangular pulses (the zero-order hold), usually followed by a lowpass filter (called an "anti-imaging filter") to remove spurious high-frequency replicas (images) of the original baseband signal.

But if the Nyquist criterion is not satisfied, adjacent copies overlap, and it is not possible in general to discern an unambiguous

Grayscale images, for example, are often represented as two-dimensional arrays (or matrices) of real numbers representing the relative intensities of pixels (picture elements) located at the intersections of row and column sample locations.

As a result, images require two independent variables, or indices, to specify each pixel uniquely—one for the row, and one for the column.

Some colorspaces such as cyan, magenta, yellow, and black (CMYK) may represent color by four dimensions.

Similar to one-dimensional discrete-time signals, images can also suffer from aliasing if the sampling resolution, or pixel density, is inadequate.

The "solution" to higher sampling in the spatial domain for this case would be to move closer to the shirt, use a higher resolution sensor, or to optically blur the image before acquiring it with the sensor using an optical low-pass filter.

When the area of the sampling spot (the size of the pixel sensor) is not large enough to provide sufficient spatial anti-aliasing, a separate anti-aliasing filter (optical low-pass filter) may be included in a camera system to reduce the MTF of the optical image.

Digital filters also apply sharpening to amplify the contrast from the lens at high spatial frequencies, which otherwise falls off rapidly at diffraction limits.

Effects of aliasing, blurring, and sharpening may be adjusted with digital filtering implemented in software, which necessarily follows the theoretical principles.

That sort of ambiguity is the reason for the strict inequality of the sampling theorem's condition.

As discussed by Shannon:[2] A similar result is true if the band does not start at zero frequency but at some higher value, and can be proved by a linear translation (corresponding physically to single-sideband modulation) of the zero-frequency case.

The corresponding interpolation function is the impulse response of an ideal brick-wall bandpass filter (as opposed to the ideal brick-wall lowpass filter used above) with cutoffs at the upper and lower edges of the specified band, which is the difference between a pair of lowpass impulse responses:

That is, one cannot conclude that information is necessarily lost just because the conditions of the sampling theorem are not satisfied; from an engineering perspective, however, it is generally safe to assume that if the sampling theorem is not satisfied then information will most likely be lost.

[7] In the 2000s, a complete theory was developed (see the section Sampling below the Nyquist rate under additional restrictions below) using compressed sensing.

A non-trivial example of exploiting extra assumptions about the signal is given by the recent field of compressed sensing, which allows for full reconstruction with a sub-Nyquist sampling rate.

Using compressed sensing techniques, the signal could be perfectly reconstructed if it is sampled at a rate slightly lower than

[B] A few lines further on, however, he adds: "but in spite of its evident importance, [it] seems not to have appeared explicitly in the literature of communication theory".

[17] Others who have independently discovered or played roles in the development of the sampling theorem have been discussed in several historical articles, for example, by Jerri[18] and by Lüke.

In later years it became known that the sampling theorem had been presented before Shannon to the Russian communication community by Kotel'nikov.

Several authors have mentioned that Someya introduced the theorem in the Japanese literature parallel to Shannon.

Their glossary of terms includes these entries: Exactly what "Nyquist's result" they are referring to remains mysterious.

was given by Nyquist as the maximum number of code elements per second that could be unambiguously resolved, assuming the peak interference is less than half a quantum step.