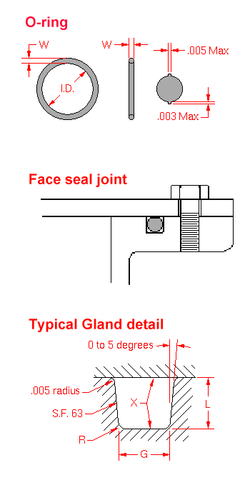

O-ring

An O-ring, also known as a packing or a toric joint, is a mechanical gasket in the shape of a torus; it is a loop of elastomer with a round cross-section, designed to be seated in a groove and compressed during assembly between two or more parts, forming a seal at the interface.

[2] O-rings are one of the most common seals used in machine design because they are inexpensive, easy to make, reliable, and have simple mounting requirements.

[9] During World War II, the US government commandeered the O-ring patent as a critical war-related item and gave the right to manufacture to other organizations.

As long as the pressure of the fluid being contained does not exceed the contact stress of the O-ring, leaking cannot occur.

For this reason, an O-ring can easily seal high pressure as long as it does not fail mechanically.

Also, vacuum systems that have to be immersed in liquid nitrogen use indium O-rings, because rubber becomes hard and brittle at low temperatures.

In some high-temperature applications, O-rings may need to be mounted in a tangentially compressed state, to compensate for the Gow-Joule effect.

Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE) Aerospace Standard 568 (AS568)[16] specifies the inside diameters, cross-sections, tolerances, and size identification codes (dash numbers) for O-rings used in sealing applications and for straight thread tube fitting boss gaskets.

[17] O-ring selection is based on chemical compatibility, application temperature, sealing pressure, lubrication requirements, durometer, size, and cost.

[18] Synthetic rubbers - Thermosets: Thermoplastics: Chemical compatibility: Although the O-ring was originally so named because of its circular cross section, there are now variations in cross-section design.

[21] This contrasts with the standard O-ring's comparatively larger single contact surfaces top and bottom.

O-ring materials may be subjected to high or low temperatures, chemical attack, vibration, abrasion, and movement.

For example, NBR seals can crack when exposed to ozone gas at very low concentrations, unless protected.

Swelling by contact with a low viscosity fluid causes an increase in dimensions, and also lowers the tensile strength of the rubber.

This was famously demonstrated on television by Caltech physics professor Richard Feynman, when he placed a small O-ring into ice-cold water, and subsequently showed its loss of flexibility before an investigative committee.

O-rings (and all other seals) work by producing positive pressure against a surface, thereby preventing leaks.

During his investigation of the launch footage, Feynman observed a small out-gassing event from the Solid Rocket Booster at the joint between two segments in the moments immediately preceding the disaster.

The escaping high-temperature gas impinged upon the external tank, and the entire vehicle was destroyed as a result.

Many O-rings now come with batch and cure-date coding, as is done in medicine production, to precisely track and control distribution.

For aerospace and military applications, O-rings are usually individually packaged and labeled with the material, cure date, and batch information.

No O-ring issues have occurred since Challenger, and they did not play a role in the Space Shuttle Columbia disaster of 2003.