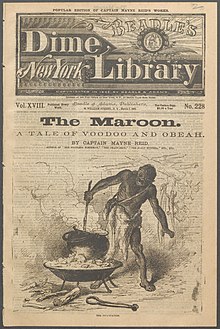

Obeah

Obeah, also spelled Obiya or Obia, is a broad term for African diasporic religious, spell-casting, and healing traditions found primarily in the former British colonies of the Caribbean.

Amid the Atlantic slave trade of the 16th to 19th centuries, thousands of West Africans, many Ashanti were transported to Caribbean colonies controlled by the British Empire.

This suppression meant that Obeah emerged as a system of practical rituals rather than as a broader communal religion akin to Haitian Vodou or Cuban Santería.

In many Caribbean countries Obeah remains technically illegal and widely denigrated, especially given the negative assessment towards it evident in religions like Evangelical Protestantism and Rastafari.

[3] It is found primarily in the former British colonies of the Caribbean,[2] namely Suriname, Jamaica, the Virgin Islands, Trinidad, Tobago, Guyana, Belize, the Bahamas, St Vincent and the Grenadines, and Barbados.

[9] For the historians Jerome Handler and Kenneth Bilby it was "a loosely defined complex involving supernatural practices largely related to healing and protection".

[10] The historian Thomas Waters called Obeah a "supernatural tradition",[11] and described how it "blended West African rituals with herbalism, Islam, Christianity and even a smattering of British folk magic".

[36][37][38] In support of this origin is the fact that the term obeah proved prominent in the British Caribbean colonies, Suriname, and the Danish Virgin Islands, all areas where large numbers of Akan speakers from the Gold Coast were introduced.

[54] Unlike other Afro-Caribbean religious traditions, such as Haitian Vodou and Cuban Santería, Obeah does not strictly centre around deities who manifest through divination and the possession of their worshippers.

[55] Obeahmen and obeahwomen are deemed able to bewitch and unwitch, heal, charm, tell fortunes, detect stolen goods, reveal unfaithful lovers, and command duppies.

[58] In Caribbean lore, it is sometimes believed that an Obeah practitioner will bear a physical disability, such as a blind eye, a club foot, or a deformed hand, and that their powers are a compensation for this.

[65] In an 1831 account from Jamaica, for instance, a slave named Polydore requested two dollars, a cock, and a pint of rum to heal a man he had made ill with his curse.

[70] At a 1755 trial in Martinique, there were reports of amulets incorporating incense, holy water, pieces of the Eucharist, wax from an Easter candle, and small crucifixes.

[72] A Jamaican case recorded in 1911 for instance involved the ritual specialist turning a key in a padlock while saying the name of an individual they wanted to prevent speaking in court.

When London gangster Mark Lambie was put on trial for kidnap and torture in 2002, both his victims and fellow gang members suggested that his powers of Obeah had made him "untouchable".

[81] A continuing source of anxiety related to Obeah was the belief that practitioners were skilled in using poisons, as mentioned in Matthew Lewis's Journal of a West India Proprietor.

Revivalists contacted spirits to expose the evil works they ascribed to the Obeah men and led public parades, which resulted in crowd hysteria that engendered violent antagonism against them.

In one 1821 case brought before court in Berbice, an enslaved woman named Madalon allegedly died as a result of being accused of malevolent obeah that caused the drivers at Op Hoop Van Beter plantation to fall ill.[84] The man implicated in her death, a spiritual worker named Willem, conducted an illegal Minje Mama dance to divine the source of the Obeah, and after she was chosen as the suspect, she was tortured to death.

[93][94][95] The notion that Obeah might be a force for generating solidarity among slaves and encouraging them to resist colonial domination was brought to the attention of European slave-owners due to several events in the 1730s.

[98][99][100] Colonial sources claimed she could quickly grow food for her starving forces,[101] and to catch British bullets and either fire them back or attack the soldiers with a machete.

[78] Be it therefore enacted ... that from and after the First Day of June (1760), any Negro or other Slave, who shall pretend to any supernatural Power, and be detected in making use of any Blood, Feathers, Parrots Beaks, Dogs teeth, Alligators Teeth, broken Bottles, Grave Dirt, Rum, Egg-shells, or any other Materials relative to the Practice of Obeah or Witchcraft, in order to delude and impose on the Minds of others, shall upon conviction thereof, before two Magistrates and three Freeholders, suffer Death or Transportation.

[110] Early Jamaican laws against Obeah reflected Christian theological viewpoints, characterising it as "pretending to have communication with the devil" or "assuming the art of witchcraft.

[115] The historian Diana Paton has argued that the laws introduced to restrict African-derived practices contributed to the developing idea that these varied traditions could be seen as a singular phenomenon, Obeah.

[122] This approach was influenced by ongoing efforts in Britain to suppress fortune tellers and astrologers there;[123] such prosecutions were thought to weed out "superstition" and thus seen as part of the empire's civilising mission.

[124] Obeah, or as it is called in some of the islands Wanga, may be described as the art of imposing upon the credulity of ignorant persons by means of feathers, bones, teeth, hairs, cat's claws, rusty nails, pieces of cloth, dirt, and other rubbish, usually contained in a wallet.

The trials of those prosecuted reveal that in this period, clients were typically approaching Obeah specialists for assistance with health, employment, luck, or success in business or legal entanglements.

[131] This material was used as a partial basis for May Robinson's 1893 article on Obeah in Folk-Lore, which in turn influenced the research of Martha Beckwith and Joseph Williams in Jamaica in the 1920s.

[11] Reflecting changing attitudes, Jamaica's Prime Minister Edward Seaga described Obeah as a form of faith healing and a part of Caribbean cultural heritage.

[135] The late 20th century saw growing migration from the West Indies to metropolitan urban centres like Miami, New York, Toronto, and London, where practitioners of Obeah interacted with followers of other Afro-Caribbean traditions like Santeria, Vodou, and Espiritismus.

[142] As Paton noted, "for a long time obeah was the ultimate signifier of the Caribbean's difference from Europe, a symbol of the region's supposed inability to be part of the modern world.