Denmark in World War II

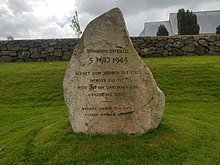

The Danish government and king functioned in a relatively normal manner until 29 August 1943, when Germany placed Denmark under direct military occupation, which lasted until the Allied victory on 5 May 1945.

[6] A resistance movement developed over the course of the war, and the vast majority of Danish Jews were rescued and sent to neutral Sweden in 1943 when German authorities ordered their internment as part of the Holocaust.

[8] The issue was finally settled when Adolf Hitler personally crossed out the words die Nordspitze Jütlands ("the Northern tip of Jutland") and replaced them with Dä, a German abbreviation for Denmark.

Although outnumbered and poorly equipped, Danish soldiers in several parts of the country put up resistance, most notably the Royal Guard in Copenhagen and units in South Jutland.

leaflets over Copenhagen calling on Danes to accept the German occupation peacefully, and claiming that Germany had occupied Denmark in order to protect it against Anglo-French attacks.

Not only was the flat Jutland territory a perfect area for the German army to operate in, the surprise attack on Copenhagen had made any attempt to defend Zealand impossible.

Few were ardent Nazis; some explored the economic possibilities of providing the German occupiers with supplies and goods; others eventually formed resistance groups towards the latter part of the war.

[citation needed] Due to the relative ease of the occupation and copious amount of dairy products, Denmark earned the nickname the Cream Front (German: Sahnefront).

"[9] The German authorities were inclined towards lenient terms with Denmark for several reasons: their only strong interest in Denmark, that of surplus agricultural products, could be supplied by price policy on food rather than by control and restriction (some German records indicate that the German administration had not fully realized this potential before the occupation took place, which can be doubted);[13] there was serious concern that the Danish economy was so dependent upon trade with Britain that the occupation would create an economic collapse, and Danish officials capitalized on that fear to get early concessions for a reasonable form of cooperation;[14] they also hoped to score propaganda points by making Denmark, in Hitler's words, "a model protectorate";[15] on top of these more practical goals, Nazi race ideology held that Danes were "fellow Nordic Aryans," and could therefore to some extent be trusted to handle their domestic affairs.

Politicians realized that they would have to try hard to maintain Denmark's privileged position by presenting a united front to the German authorities, so all of the mainstream democratic parties formed a new government together.

The Danish government was dominated by Social Democrats, including the pre-war prime minister Thorvald Stauning, who had been strongly opposed to the Nazi party.

[citation needed] Nonetheless, his party pursued a strategy of cooperation, hoping to maintain democracy and Danish control in Denmark for as long as possible.

It agreed that Kryssing should be removed in its meeting on 2 July 1941, but this decision was later withdrawn when Erik Scavenius—who had not attended the original meeting—returned from negotiations and announced that he had reached an agreement with Renthe-Fink that soldiers wishing to join this corps could be given leave until further notice.

As Berlin grew tired of waiting, Joachim von Ribbentrop called Copenhagen on 23 November threatening to "cancel the peaceful occupation" unless Denmark complied.

On 23 November, the Wehrmacht in Denmark was put on alert, and Renthe-Fink met Stauning and Foreign Minister Munch at 10 AM stating that there would be no room for "parliamentary excuses".

Scavenius had a strict mandate not to change a sentence and stated that he would be unable to return to Copenhagen with a different content from the one agreed upon, but that he was willing to reopen negotiations to clarify the matter further.

Nonetheless, for Scavenius it was a strong setback that the four clauses would now only get the status of a unilateral Danish declaration (Aktennotitz) with a comment on it by Fink that its content "no doubt" was in compliance with the pact.

Lidegaard comments that the old man remained defiant: during a conversation with Ribbentrop in which the latter complained about the "barbarous cannibalism" of Russian POWs, Scavenius rhetorically asked if that statement meant that Germany didn't feed her prisoners.

At the same time a large demonstration gathered outside of Parliament, which led the Minister of Justice, Eigil Thune Jacobsen [da] to remark that he did not like to see Danish police beating up students singing patriotic songs.

The voter turnout was 89.5%, the highest in any Danish parliamentary election, and 94% cast their ballots for one of the democratic parties behind the cooperation policy while 2.2% voted for the anti-cooperation Dansk Samling.

A high-profile resister was former government minister John Christmas Møller, who had fled to England in 1942 and became a widely popular commentator because of his broadcasts to the nation on BBC radio.

Nonetheless, the Danish resistance movement had some successes, such as on D-Day when the train network in Denmark was disrupted for days, delaying the arrival of German reinforcements in Normandy.

The government had foreseen the possibility of coal and oil shortages and had stockpiled some before the war, which, combined with rationing, prevented some of the worst potential problems from coming to the country.

After the war there was some effort to find and punish profiteers, but the consequences and scope of these trials were far less severe than in many other countries, largely a reflection of the general acceptance of the realistic need for cooperation with Germany.

In July 1945, two months after the liberation of Denmark, the Danish Parliament passed an emergency law initiating a currency reform, making all old banknotes void.

Any amount above this level would be deposited in an escrow account and only released or exchanged following scrutiny by tax officials examining the validity of the person's statement about the origins of this wealth.

[citation needed] After the end of hostilities, over two thousand German prisoners of war were made to clear the vast minefields that had been laid on the west coast of Jutland, nearly half of them being either killed or wounded in the process.

[49][50][better source needed] In the final weeks of the war, between 9 February and 9 May, several hundred thousand German refugees fled across the Baltic Sea, fleeing the advancing Soviet Army.

The reason for this was not only anti-German resentment, but also lack of resources, the time needed to rebuild administrative structures, and the fear of epidemic diseases which were highly prevalent among the refugees.

In the camps, there was school education for children up to the upper secondary level, work duty for adults, study circles, theatre, music, and self-issued German newspapers.