Officers' Association

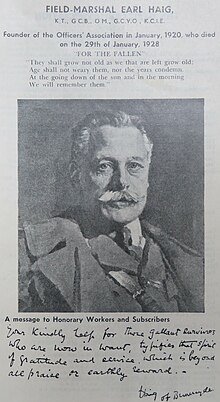

The Officers' Association (OA) is a registered charity in the United Kingdom, supporting Former-officers and their families providing advice and financial assistance, it was founded in February 1920 and incorporated under Royal Charter on 30 June 1921.

The Officers' Association was formed after the First World War, principally in response to the widely publicised new social phenomenon of 'the moneyless former-officer',[1] categorised as being reduced by circumstances to a state of distress and penury.

Applying the same principle used by the RPF and adopted by many later successful fundraising campaigns, he made his appeal in the media of the day to generate public interest in and concern for the fate of deployed troops and their dependents.

It was based at 12, Dean's Yard, Westminster and enjoyed support from establishment figures and the patronage of Their Majesties King George V and Queen Mary, the First Lord of the Admiralty and the Secretary of State for War.

From late 1916 onwards, given impetus by the introduction of conscription under the Military Service Act, 1916 and the enormity of the casualties resulting from the Somme campaign, informal and disparate groups of former servicemen began to coalesce into vocal and politically active national representative bodies.

Lord Derby, by then the Secretary of State for War, had direct professional and personal interests in countering the increasing political influence now being exerted on government performance and policy by the Association and especially by the Federation.

For example, a case file note for Lieutenant Colonel J P Hunt CMG, DSO (and Bar), DCM, who had been a pre-war Colour Sergeant and re-enlisted in 1914 at age 41, was commissioned into the Royal Dublin Fusiliers in 1915 and by 1917 was commanding 9th Battalion in France.

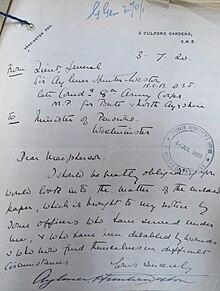

On 3 July 1920, for example, Lieutenant General Sir Aylmer Hunter-Weston (late Commander 8th Army Corps and MP for Bute and North Ayrshire) wrote to the Pensions Minister,[9] Ian Macpherson, forwarding papers brought to his attention by officers who had been "disabled by wounds and now find themselves in difficulties".

An illustration of this class consciousness among ranker officers can be seen through a letter to the Secretary of State for War[13] on 14 August 1919, in which Captain Thomas Wadner, King's Royal Rifle Corps, was enquiring as to the progress of his delayed application to resign his commission.

Wadner was a ranker officer who had enlisted in 1904 and been commissioned in August 1914 (incidentally, on the same day as his brother), he has been wounded while leading his Platoon in action near Ypres in November 1914 and captured and held a Prisoner of War in Germany until January 1919.

He describes the reason for his resignation as him having family problems and wanting to start in business "... in my own class of life..." The ranks such men as Wadner achieved, and the roles and responsibilities incumbent upon them in the positions to which they rose, may have given some of them over-inflated expectations in terms of post-war, civilian status, employment and salary.

Haig went on to describe the individuals whose services he had been able to secure for the roles of Chairman of the Central Committee; Secretary and Financial Advisor and chairmen of groups dealing with Employment, Housing; Families and Disabled Officers.

He described the chief objects of this Association as: "to coordinate the work of the various Societies, to prevent overlapping and thus avoid any waste of money, and to co-operate with the Government departments whose efforts are directed towards the assistance of those officers who have suffered as a result of the Great War".

Haig was keen to dispel any lingering belief that they had private wealth, noting that "the majority of the former-officers now in need of assistance obtained their commissions from the ranks", making it clear that they were not from the monied middle classes and implying that in so doing, they had lost any entitlement to ex-rankers' benefits.

On 30 July, a meeting of members of the three separate Executive Committees was held in the Central Hall, Westminster, under the chairmanship of General Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien (who had been removed from command of the 2nd Army in April 1915 for baulking at orders which, in his view, would have led to unacceptable and avoidable casualties).

On the morning of Sunday 15 May 1921, the conference delegates trooped from Queen's Hall to the Cenotaph, where four men laid a laurel wreath which contained the emblems of the four separate organisations in a symbolic gesture confirming the amalgamation, before marching on to the Tomb of the Unknown Warrior in Westminster Abbey.

This is illustrated clearly in the correspondence of ex-Captain William Aldworth DSO, a Ranker Officer who had enlisted in 1896, served in South Africa and was commissioned from the ranks in November 1914, before retiring in 1920 with a gratuity (but no pension).

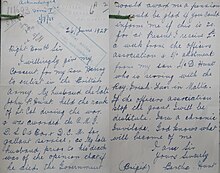

In gratitude, one beneficiary wrote, offering: 'You were courageous enough to advance me the cash to start my business when you could scarcely have known whether it would be a success or not,'; another 'a new lease of life when I was down and out' and another 'the day I walked into 48 Grosvenor Square I was in rags and hungry.

The strong inference was that the OA's Employment Branch provided not only a job placement service but somewhere for disabled and distressed former-officers to meet people who had shared experiences, who were like-minded and who might understand and be sympathetic to their situation and plight.

At a time when mental health and combat trauma were not well recognised or understood and for which limited provision or treatment was available, and when so many people were afflicted and sympathy was in short supply, the Branch fulfilled its intended purpose as well as providing a vital, if unintended and largely unrecognised social service.

A Ministry survey and cost estimate dated November 1920, describes Rotherfield Court as comprising a mansion house, two gate lodges, stables and outbuildings set in 8 acres of grounds.

A briefing note of 23 September makes reference to a deputation of ranker officers to the Secretary of State in June, following which an undertaking was given to see what could be done to support certain hard cases concerning widows in distress.

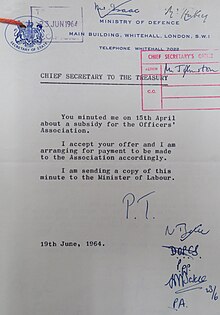

Despite this increasing separation, the OA continued to rely for the great majority of its income, on the annual grant that had been made since the arrangements and undertakings on fundraising and funding agreed at the time of the Legion's founding.

The employment situation was further complicated by the nationalisation of about 20% of the British economy, which saw privately-owned coal, railway, road transport, civil aviation, electricity and gas and steel industries and the Bank of England brought into state ownership, albeit with no public finances available for investment.

An issue not addressed by immediate post-war welfare reforms was suitable residential accommodation in which aged former-officers in declining health who had outlived their relations and faced the prospect of loneliness in a state of penury, could spend the final years of their lives.

The OA had benefited from the support of the numerous volunteers who made this endeavour a success, including, in Belgium, Mme M. de Callatey, a decorated veteran of the Belgian resistance, who was remembered with great fondness by the children who enjoyed these holidays.

Many employers were aware of the potential benefits senior officers could bring, especially those with specialist qualifications readily recognised in civil life, but who found it difficult to integrate them into their promotion hierarchies and their superannuation schemes.

This included individual career consultations and advice as well as hosting a jobs board which, typically, advertised around a thousand executive appointments annually; all deemed to capitalise on the valuable experience that former-officers had gained during their service.

In 2020, in order to reduce costs and to capitalise on the changes in working practice that had resulted from the COVID-19 pandemic, the Headquarters moved to serviced offices at 40rty, Reading, with many staff, especially those resident in London, becoming home-based workers.

Echoing in many ways the reorganisation that had attended its arrangement with the British Legion, the OA transferred its Employment Branch, a number of other key staff and a proportion of its investments to FEC in order to ensure continuity of service and that the new charity had the best possible start.