Omaha Beach

[1] "Omaha" refers to an 8-kilometer (5 mi) section of the coast of Normandy, France, facing the English Channel, from east of Sainte-Honorine-des-Pertes to west of Vierville-sur-Mer on the right bank of the Douve river estuary.

The coastline of Normandy was divided into sixteen sectors, which were assigned code names using a spelling-alphabet - from Able, west of Omaha, to Roger on the east flank of Sword.

[6][7] Coastal troop deployments, comprising five companies of infantry, were concentrated mostly at 15 strongpoints called Widerstandsnester ("resistance nests"), numbered WN-60 in the east to WN-74 near Vierville in the west, located primarily around the entrances to the draws and protected by minefields and wire.

Post-action reports still documented the original estimate and assumed that the 352nd had been deployed to the coastal defenses by chance, a few days previously, as part of an anti-invasion exercise.

V Corps' 56th Signal Battalion was responsible for communications on Omaha with the fleet offshore, especially routing requests for naval gunfire support to the destroyers and USS Arkansas.

[27] While reviewing Allied troops in England training for D-Day, General Omar Bradley promised that the Germans on the beach would be blasted with naval gunfire before the landing.

[31] At 06:00, 448 Consolidated B-24 Liberator heavy bombers of the United States Army Air Forces, having already completed one bombing mission over Omaha late the previous day, returned.

Although the Rangers at Pointe-du-Hoc were greatly assisted in their assault of the cliffs by the Satterlee and Talybont, elsewhere the air and naval bombardment was not so effective, and the German beach defenses and supporting artillery remained largely intact.

[33] Later analysis of naval support during the pre-landing phase concluded that the navy had provided inadequate bombardment, given the size and extent of the planned assault.

On the 16th RCT front, the landing boats passed struggling men in life preservers and on rafts, survivors of the DD tanks which had sunk in the rough sea.

[49] The scattering of the boats was most evident on the 16th RCT front, where parts of E/16, F/16 and E/116 had intermingled, making it difficult for sections to come together to improvise company assaults that might have reversed the situation caused by the mis-landings.

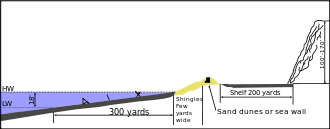

In the east at Fox Green and the adjacent stretch of Easy Red, scattered elements of three companies were reduced to half strength by the time they gained the relative safety of the shingle, many of them having crawled the 300 yards (270 m) of beach just ahead of the incoming tide.

Within 15 minutes of landing at Dog Green on the western end of the beach, A/116 had been cut to pieces, the leaders among the 120 or so casualties,[49][52][53][a] the survivors reduced to seeking cover at the water's edge or behind obstacles.

[citation needed] L/16 eventually landed, 30 minutes late, to the left of Fox Green, taking casualties as the boats ran in and more as they crossed the 200 yards (180 m) of beach.

Working under intense fire, the engineers set about their task of clearing gaps through the beach obstacles—work made more difficult by loss of equipment, and by infantry passing through or taking cover behind the obstacles they were trying to blow.

[61] To their left, mainly between the draws on the Easy Green/Easy Red boundary, the 116th RCT's support battalion landed without too much loss, although they did become scattered, and were too disorganized to play any immediate part in an assault on the bluffs.

Many half-tracks, jeeps and trucks foundered in deep water; those that made it ashore soon became jammed up on the narrowing beach, making easy targets for the German defenders.

In places, small groups of men, sometimes scratched together from different companies, in some cases from different divisions, were "...inspired, encouraged or bullied..."[66] out of the relative safety of the shingle, starting the dangerous task of reducing the defenses atop the bluffs.

The command party established themselves at the top of the bluff, and elements of G/116 and H/116 joined them, having earlier moved laterally along the beach, and now the narrow front had widened to the east.

Progress was slowed by mines on the slopes of the bluff, but elements of all three rifle companies, as well as a stray section of G/116, had gained the top by 09:00, causing the defenders at WN-62 to mistakenly report that both WN-65 and WN-66 had been taken.

Finding targets difficult to spot, and in fear of hitting their own troops, the big guns of the battleships and cruisers concentrated fire on the flanks of the beaches.

The German emphasis on this Main Line of Resistance (MLR) meant that defenses further inland were significantly weaker, and based on small pockets of prepared positions smaller than company sized in strength.

[86] As an example of the effectiveness of German defenses despite weakness in numbers, the 5th Ranger battalion was halted in its advance inland by a single machine gun position hidden in a hedgerow.

The success of the MLR in blocking the movement of heavy weapons off the beach meant that, after four hours, the Rangers were forced to give up on attempts to move them any further inland.

Thirteen DUKWs carried the 111th Field Artillery Battalion of the 116th RCT; five were swamped soon after disembarking from the LCT, four were lost as they circled in the rendezvous area while waiting to land, and one capsized as they turned for the beach.

[95] Observing the build-up of shipping off the beach, and in an attempt to contain what were regarded as minor penetrations at Omaha, a battalion was detached from the 915th Regiment being deployed against the British to the east.

[97] Preparations were made to bring up units stationed for the defense of Brittany, southwest of Normandy, but these would not arrive quickly and would be subject to losses inflicted in transit by overwhelming Allied air superiority.

The British mobile radars, being able to detect the range, bearing and height of potential enemy aircraft, were ideally suited for this role, provided they could be located on favorable sites and were available for immediate use on the night of the landings.

In order to provide this air cover, three Base Defence Wings (re-designated as "Sectors" – BDS - in May 1944)[99] were begun to be formed from 1 January 1944 with the appointment of Group Captain Moseby as the Commanding Officer of No.

By the morning of June 9 this regiment had taken Isigny and on the evening of the following day forward patrols established contact with the 101st Airborne Division, thus linking Omaha with Utah.